TEMPLES & SHRINES - 1 庙宇莊厳. 殿堂清静

This is the first of two pages on shrines, temples, and the ceremonial halls of Chinese organizations. Neither page gives details about the beliefs of the religions involved. Those wishing to learn more about the tenets of Buddhism, Taoism, Confucianism, and the less formal belief systems of North American Chinese will find them discussed on many other websites. Our concern here is with the physical aspects of religious and secular ritual, and what these tell us about the histories, societies, and psychologies of Chinese immigrants who found themselves in a new land, empty of the ancient religious symbols and sacred places that had sustained their ancestors' spiritual welfare.

The categories of shrine, temple, and organization hall tend to overlap. A shrine is a non-public room or part of such a room dedicated to religious or partly religious activity. A temple is a space that is likewise dedicated but open, more or less, to the general Chinese public. An organization hall contains a shrine-like area but is primarily secular in function. Users should click on the Associations page for more data on halls. For more on shrines and temples, click on Temples-2,

The page does not cover Christian churches, which often played important roles in early Northwestern Chinese communities. It is hoped that a new page on churches and missionaries, both Caucasian and Chinese, can be included in the future.

Tam Kung Temple, Victoria, BC 卑斯省域多利谭公庙

The oldest active Chinese temple in Canada is on the fourth floor of a building at Fisgard and Government Streets in Victoria's Chinatown. The building is owned by the local Hakka association, the Yen Wo Society 客属人和会馆,

but the temple itself, founded in 1875 by Ngai Sze 魏泗, is older than the association. According to David Chuenyan Lai, it is the oldest in Canada. Along with a few temples in California (notably the 1852 Tin How Temple in San Francisco and the 1874 Won Lim Temple at Weaverville) that are still active and continuously in use, it is one of the oldest such temples in North America.

Tam Kung 谭公 is a Daoist deity, popular in the South China around Hong Kong and Macau. Professor Lai gives his background. Tam Kung was a real human being who lived in the 13th century. One (Hakka) story has it that he was a Hakka elder in Kowloon, now part of Hong Kong, who aided the last emperor of the Song dynasty, an 8 year-old boy, in his flight from the invading armies of the Mongol ruler Kublai Khan. Tam Kung with his Hakka community were executed by the Mongols for his patriotic efforts, but later he was deified and temples were built in his honor.

The age of Victoria's Tam Kung temple, known from a single historical record, is confirmed by the dates inscribed along with the temple's name on several of the objects that form part of the temple furnishings. Although a fire in the 1990s destroyed many of those furnishings, luckily several such dated pieces survived.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Objects with Early Dates, Tam Kung Temple, Victoria.

Date Object

Object

Reading in English Chinese

Reading in English Chinese

Donors (names in Pinyin)

Donors (names in Pinyin)

1 1887

1887 Bronze censer

Bronze censer  "Made in Canton by 光绪十三年孟秋月吉旦

"Made in Canton by 光绪十三年孟秋月吉旦 Luo Basheng, He Shenjing,

Luo Basheng, He Shenjing,

2 1887

1887 A cast iron bell

A cast iron bell  No maker's name

No maker's name 谭公仙圣爷爷光绪十三

谭公仙圣爷爷光绪十三 Same as above

Same as above

3 1894

1894 (R side) Vertical

(R side) Vertical  "Gallantry subdues 威镇边疆咸钦地利.

"Gallantry subdues 威镇边疆咸钦地利.

4 1894 (L side) Vertical

1894 (L side) Vertical  "Blessings cover the 恩垂梓里共仰人和. Ren Wo Co., Vancouver

"Blessings cover the 恩垂梓里共仰人和. Ren Wo Co., Vancouver

5 No date Horizontal plaque.

No date Horizontal plaque.

谭公仙圣. 陈乐三敬书 Chen Lesan

谭公仙圣. 陈乐三敬书 Chen Lesan

6 1894

1894 Bronze censer with "Made in Hong Kong 光绪二十年仲秋吉旦立 Xiao Guanmei

Bronze censer with "Made in Hong Kong 光绪二十年仲秋吉旦立 Xiao Guanmei

7 1897

1897 A five-piece altar set

A five-piece altar set

谭公仙圣. 光绪二十三 Li Qi & wife

谭公仙圣. 光绪二十三 Li Qi & wife

8 1897

1897 A table façade carved "Made in Lianxing

A table façade carved "Made in Lianxing 粤东省 联兴街光绪二

粤东省 联兴街光绪二

9 1903

1903 A stone censer with

A stone censer with

光绪癸卯年立谭公仙

光绪癸卯年立谭公仙 Lai Rifang, Chen Jinsheng

Lai Rifang, Chen Jinsheng

10 1906 Bronze censer with "Made in Guangzhou 丙午年仲春嗀旦谭公仙 Liu Jingyao

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Data on Tam Kung history come from an article by David Chuenyan Lai, "Tam Kung Feted" in [Victoria} Times-Colonist 23 May 2004 p D12

5. Tam Kung Horizontal Plaque

7. Pewter Altar Set, 1897

1, 6, 10. L-R: Censers. 1887, 1894, 1906

9. Stone receptor for wine offering, 1903

2. Cast Iron Bell, 1887

Bell Stand with Drum and Bell

2. Date on Back of Bell: "Guangxu 13th Year"

Victoria's Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association (CCBA) or Zhonghua Huiguan 中華會館 was founded in 1885. The shrine that is now on the third floor of the CCBA-supported Chinese Public School was dedicated in the same year. The question is, did the shrine belong to an independent temple or has it always been part of the CCBA?

The pewter censers on the outer altar table bear the temple's original name: Liesheng Gong 列圣宫 or "Temple of Many Gods." In the U.S., most such temples seem to have been originally independent, although often taken over by more secular organizations within a few decades of their founding. Amos and Wong say that the shrine was moved to the school in 1966 from the CCBA's headquarters on Fisgard Street [Note 1]. Apparently the temple has been part of the CCBA since its founding in 1885 but already existed on the same spot when the CCBA built its headquarters there.

1857 The earliest picture of an American Chinese temple 最早华人庙宇插图 [10/15/2010, revised 02/21/2011]

<1860 The North God in North America 飞越太平洋的北帝 [10/25/2010]

1861-6 The oldest Chinese temples on this continent 北美洲最早的华人庙宇 [revised 06/11/2013]

1861 The oldest Chinese North American temple object [10/26/2015]

1863 The second oldest Chinese North American temple object [10/25/2010, revised 10/26/2015]

(1852) FOUND! An even older but now-vanished temple/association inscription [10/19/10, revised 06/11/13]

1874-1907 Tianyun: Secret dates for a revolutionary cause, identified for the first time in North America

1874-1909 Cast iron bells in North American Chinese temples 西北角寺庙法器 – 生铁钟, 云板,

1837-1900 Bells as markers of trade and migration. [09/15/2013]

1870s-present Leishenggong: the dominant type of North American Chinese temple [011/04/2013]

1875-1887 Victoria's Tam Kung Temple 卑斯省域多利谭公庙 [11/30/2009]

1880s-1904 Suijing Bo in the Northwest: a once-obscure deity makes it big 山不在高有仙则灵: 绥靖伯庙

1885 The CCBA's shrine in Victoria: was it originally theirs? 加拿大域多利埠中华会馆大堂 [11/02/10,

1888-1890 Lewiston's Beuk Aie Temple: memorial for a massacre? 重修北帝庙 - 记念蛇河华工浴血案?

1902 The only known Chinese temples in Seattle before modern times [06/10/2012]

1911 An art nouveau landmark: the Hook Sin Tong Building in Victoria 巍巍大厦, 福善有堂 [05/24/2010]

The Oldest Surviving Chinese Temples in North America

北美洲最早的华人庙宇铭文记录 - 加州 美利允市 北溪庙

The setting up of places dedicated to traditional worship marked important milestones in the history of North American Chinese. The first such place was undoubtedly in San Francisco. Most writers (note 1) agree that the earliest temple was in present-day Chinatown: either a Kong Chow 岡州 (Gang Zhou) Association temple on Pine Street (recently moved to Stockton Street) or a temple dedicated to Tin How 天后 (Tian Hou) on Waverly Place. Both are claimed to have existed since the early 1850s. However, whether one accepts such claims depends on how one understands historical continuity.

It is not enough to rely on secondary sources or oral tradition. It is also not enough just to cite primary sources which state that a temple dedicated to the same deity or sponsored by the same organization formerly existed in the same area as the present one, as is the case with both the Tin How and Kong Chow temples. Think of the modern Druids, the country of Benin, or Abercrombie & Fitch stores: having the same name does not indicate essential continuity. Ideally, one wants to see continuous institutional records or an actual structure built for the original temple at the time of founding. As neither form of evidence is available in the case of the San Francisco temples, partly due to the earthquake and fire of 1906, one must turn to another kind of proof: dated temple furnishings such as bells or drums, inscription boards, altar carvings, censers, hangings, and so forth. As was the case in several smaller Californian cities, such furnishings were normally moved when temples are rebuilt or relocated. When furnishings bear the date of donation and the name of the temple or sponsoring institution, they constitute convincing evidence that the temple in question existed at that time in the past.

The purpose of this article is to find the oldest surviving Chinese temple on this continent. Which temple has the earliest dated furnishings? Where and how old is it?

For archaeological objects, one has to locate a convincingly sealed context: for instance, a deposit under a building constructed in about 1860, For historical objects, the key is finding epigraphic dates (that is, dates in contemporary inscriptions) from the reign of Emperor Xianfeng 咸豐 (1851-61), on objects known to have been made for and used by Chinese North Americans. The following article shows that an inscription with a Xianfeng 2nd Year (1852) date was recorded in San Francisco by a 19th century missionary. We would love to see an actual inscription like that, from San Francisco or anywhere else in the U.S. or Canada.

The two “oldest” San Francisco temples, the Kong Chow temple on Stockton Street or the Tin How temple on Waverly Place, do not possess objects that prove their age. The Tin How temple does have an iron bell dated to the 13th year of the Tongzhi 同治 reign, or 1874, but that bell was made for a San Shing Temple 三圣宫, not for Tin How. And devotees of the fine Guandi image in the Kong Chow Temple claim that their statue was formerly in a long-gone shrine founded in 1852 by a predecessor of the Kong Chow Association. This may be so. However, there is no proof except pious legend. In Taoism as in Christianity, religious objects deemed to be especially holy or in Chinese terms, leng (efficacious), are often assigned very early dates by worshipers. And indeed, the Kong Chow Guandi is reputed to be exceptionally leng, but that does not mean that it is also exceptionally old.

Both of the oldest San Francisco temples may indeed have been founded in the nineteenth century. Early news articles show that the present Kong Chow temple is almost certainly a direct descendant of the above-mentioned 1852 shrine, and the Tin How temple probably is connected with one of San Francisco's 19th century Tian Hou temples. But neither temple seems to have existed in any other sense before its earliest inscription -- Kong Chow in 1909 and Tin How in about 1910.

Three temples outside San Francisco are older. Oroville and Weaverville both have a number of objects, including the inscribed board and ceramic censer shown here, with 1874 -- Tongzhi 13 -- dates. It is not clear why that particular year was so popular for donating temple furnishings. Was 1874 an especially prosperous or propitious time for California Chinese? We do not know.

And in any case, both temples and Marysville as well, contain objects that are earlier than 1874. On present evidence, the oldest in Marysville's Bok Kai Temple 北溪庙 is a pair of inscribed boards dated to Tongzhi 5, or AD 1866.

Bell in Tin How/Tian Hou temple, San Francisco, 1874 (Tongzhi 13th year), probably made in Foshan near Guangzhou for a "Three Gods Temple"

三藩市

華埠天后庙

铁钟

Inscribed board in Oroville temple, 1874 "-----zhi 13th year"

加州奧羅維爾市

華人庙

Censer in Weaverville temple, "Tongzhi 13th year"

加州雲林庙 同治十三年瓷香炉

Inscribed board in Marysville's Bok Kai temple, 1866 "Tongzhi 5th year"

加州 美利允市 北溪庙

Note 1: Mariann Kaye Wells, Chinese Temples in California, U of California Berkeley MA Thesis,1962, pp 36-7, 48; William Hoy, Kong Chow Temple, 1939 (quoted by Wells); Frederick J. Masters, “Pagan Temples in San Francisco,” The Californian, November 1892, p 732, 734

Note 2: The Oroville temple complex is the most fully published Chinese religious institution temple in the U.S.: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/collections/oroville/

Note 3: For the earliest Chinese temple objects in Canada (in Victoria's Tam Kung temple), see above. They are about twenty years later than the earliest temple objects in California.

| ||||

| ||||

Bok Kai Temple, 2008 美利允市 北溪庙正门

Cast Iron Bells in North American and Hawai'ian Chinese Temples

西北角寺庙法器 – 生铁钟, 云板, 鼎炉

China, unlike Europe, traditionally made bells from iron as well as bronze. The secret was high-carbon "white" (gray-brown on the outside but silvery white when freshly broken) cast iron, which Chinese foundrymen had discovered by 400 BC, almost 1700 years before European iron makers began producing it. White cast iron, with a carbon content higher than 4%, is brittle when thin and extremely hard--too hard to file or cut except by gem-working methods. On the other hand, it is easy to cast, much cheaper than bronze, and has a property that is unique among the various kinds of iron: due to a low damping capacity, it rings with a clear, sustained note when struck. Like high-tin bronze and unlike most other metals and alloys, it makes excellent bells.

Bells of white cast iron had long been common in China, although still rare in Europe, when Chinese immigrants first arrived in North America in the 19th century. The low price of cast iron was attractive to early immigrants who wished to build a Taoist or Buddhist temple, who did not have money to burn, and who felt that a good bell and drum were essential for temple worship. Iron bells had another advantage. Their surfaces were so hard that it was almost impossible to alter inscriptions, including the names of donors, that had been cut into the face of the mold in which the bell was cast.

1. A suspension loop in the shape of an animal with splayed-out legs, representing the sprue through which the molten iron was poured into the mold.

2. A dome-shaped shoulder, with raised lines where the different parts of the mold were joined before casting; in southern (unlike northern) China, the shoulder never has purpose-made holes.

3. A vertical body for percussion, with cast-in inscriptions that include (a) a credit line giving the names of donors; (b) the date of manufacture, (c) a blessing (usually fengdiao yushun, guotai minan 风调雨顺, 国泰民安 "wind abated, rain calmed, nation at peace, the people secure"); and (d) the weight of the bell and the name of the workshop that made it.

4. An out-turned skirt at the bottom; in southern (unlike northern) China the skirt is rarely scalloped.

Other temple furnishings too were often made of white cast iron. At temples in China itself, large cast iron incense burners are common, as are cast iron statues, small pagodas, woks and other pans, and flat gongs (yunban). As shown below, several such objects exist in surviving North American temples.

The following list may now (October, 2015) be nearly complete. However, the editors would appreciate information about any relevant objects they may have missed.

Location

Tin How Temple San Francisco

天后庙

Oroville Temple California

Bok Kai Temple Marysville, California.

Tam Kung Temple Victoria, British Columbia

Gee How Oak Tin Shrine, Portland, Oregon, 至孝篤親公所

San Francisco

Weaverville, California

雲林庙

Guanyin Temple,

Honolulu, Hawai'i

Tianhou Temple (Lum Sai Ho Tong), Honolulu, Hawai'i

Merced County Courthouse Museum, Merced, California

(formerly at Suey Sing)

Dart Coon Club

Victoria, BC 达权社

Chinese Consolidated

Benevolent Assoc-iation, Victoria, BC

Ng Shing Gong Temple, San Jose, California

Object & Date

Bell, 1874

同治十三年

季冬吉旦

Large tripod censer, 1875

Bell, 1882

光绪八年

壬午孟冬

Bell. 1887

光绪十三年

孟秋吉旦

Bell,1888

光绪十三年

Bell, 1909 宣统元年

仲秋吉日

Cloud Plate (Yun Ban) Gong, no date

Bell, date removed

[note 1]

Bell, no date (early 20th century?)

Bell, no date (ca. 1875-1895?)

Bell, no date (1880s-1890s)

Bell, 1885

光绪十一年

Bell, 1889

Made by and for

Xinchang Foundry for Three Deities Shrine

信昌炉造/三圣殿

Shengji Foundry at

Chanshan 禅山盛记炉造

[Foshan 佛山]

Xinchang Foundry for All

Deities Temple

信昌炉造/列圣宫

No foundry named, made

for the deified Tam Kung

谭公仙圣爷爷

Made by Chang Fu, Guang-dong, for Suijing Bo Temple, 广东长孚造/绥靖伯庙

Made by Hexing Foundry for Kong Chow Old Temple

合兴炉造/岡州古庙

Xinchang Foundry

信昌炉造

Made by Longsheng Foundry, Guangdong. 粤东隆盛炉造

Foshan style

Xinchang Foundry

信昌炉造

Gongxing Foundry

公兴炉炷

Made by Longsheng Foundry, 隆盛炉造

Xinchang Foundry

信昌炉造

Other Inscriptions

沐恩弟子

张琦玉, 温盘, 戴廷斌, 戴发戴廷祯, 戴二戴泰安, 温六仝敬送

8 male donors with three surnames

27 donors with 11 surnames

风调雨顺. 国泰民安

沐恩弟子

黄长光, 林阿富,伍王华仝人敬

3 male donors with different surnames

风调雨顺. 国泰民安

沐恩弟子

骆拔 陞, 何申清, 邓维绍, 福绵

堂, 魏泗, 俆清华, 等仝敬造

风调雨顺. 国泰民安

"wind abated, rain calmed, nation at peace, the people secure"

风调雨顺. 国泰民安

"wind abated, etc."

日, 月, no names

风调雨顺. 国泰民安

"wind abated, etc."

风调雨顺. 国泰民安

"wind abated, etc."

马些雪地.水陆平安

"Merced City, Be Safe on Water

and Land"

风调雨顺. 国泰民安

域哆唎埠.致公堂立.

"wind abated, etc." plus

"Yudouli [Victoria] Chee Kong Tong .."

风调雨顺. 国泰民安. 徐东海堂敬送

"wind abated, etc."plus "Donated by Xudinghai Tang" [Xu Clan Association]

Made for Wu Sheng-Gong 五圣宫.

风调..民安, "wind abated, etc."

Foshan ("Buddha Hill"), southwest of Guangzhou (or Canton), was an old and busy industrial town known for its foundries and ceramics (click here to see Foshan opium pipes). Many of the cast iron temple objects still to be seen in southern China were made there. Five out of the six foundries listed above were in Foshan. The Xinchang 信昌foundry seems to have been especially popular: its products are reported from Chinatowns in Hui-an (Vietnam), Penang (Malaysia), and Innisfail (Australia) as well as at the above five temples in California [Note 2]. In Foshan itself a cast 3-legged toad sculpture bears the name of Xinchang, and in 1870 the same foundry cast a large tripod censer for the City God temple in Luoding, Guangdong province.

Iron temple bells usually have four parts:

Tam Kung Temple, Victoria, B.C. Won Lim Temple, Weaverville, California Kong Chow Temple, San Francisco

Kong Chow Temple, San Francisco

加拿大域多利谭公庙

加州雲林庙

加州雲林庙

三藩市岡州古庙

三藩市岡州古庙

Back of bell showing

deleted inscription

An Art Nouveau Landmark: Victoria's Hook Sin Tong Building

巍巍大厦. 福善有堂

One of the most extraordinary Chinese interiors in North America was commissioned by the Hook Sin Tong, a society founded in Victoria by immigrants from Heung Shan 香山 (later Zhongshan) in Guangdong. Unlike other associations in Canadian and American Chinatowns, the Hook Sing Tong had a meeting hall that showed a complete rethinking of how such a hall and its shrine shiould be designed. The hall was decorated consstently according to a then-modern aesthetic concept that would have been more at home in a building in Shanghai or Chicago than in a conservative North American Chinatown. A uniform clor scheme was imposed. Stained glass was used extensively. And the place where the shrine would normally be was occupied by a wall without an altar but with a portrait of Zhongshan's most famous son, Sun Yat-Sen (or Sun Zhongshan), the first president of the Chinese Republic. For more on the Hook Sun Tong building, click here.

Hook Sin Tong, 3rd floor main hall,

ceiling dome

Although not on the standard Victoria tourist route, the hall is open to the public on certain days of the year. More data and pictures of the Hook Sin Tong building will be found on the "Organizations" page of this website

A once-obscure deity makes it big: Suijing Bo, the Pacifier Duke 山不在高有仙则灵: 绥靖伯庙

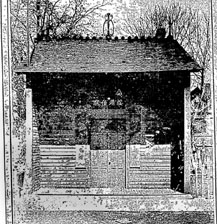

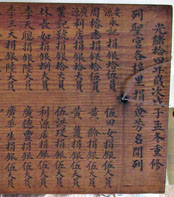

Chinese temples and shrines in the Pacific Northwest tend to feature the deities most popular among North American Chinese: the Northern God 北帝 (a.k.a. Beuk Aie, Bok Kai), the God of War 关帝 (Guandi, Guangong, etc), the Empress of Heaven 天后 (Tianhou, Goddess of Mariners), or the Goddess of Mercy 观音 (Guanyin or, in Sanskrit, Avalokitesvara). A few, however, include a much less famous deity: Duke Suijing 绥 靖 伯, noted in his earthly life as a fighter against bandits and, after deification, as a protector against epidemics. The latter role contributed to the spread of reverence for him during the 19th century, from a few temples in the Taishanese-speaking part of Guangdong to many towns in southern China and Southeast Asia. The editors know of five temples in North America that include him (Fig. 1). Three were built in 1860-1880, one in 1900, and one in 1904.

Among Suijing Bo's most regular worshipers were members of the Chen 陈 (also spelled as Chin, Chinn, and Chan in America and Tan in Southeast Asia) clan (or family name) association. This was because he too was a Chen, with the personal name Zhongzhen 仲真. Due to his success as a military official in Taishan back in the 12th century, his clan had long revered him as “the Honorable Chen Official.” The clan's reverence must have increased after 1844 when the Imperial court officially recognized Zhongzhen as a deity, giving him the name Suijing, the Pacifier, with the rank of Bo, or Duke.

The Chen's temple in Oroville, California, has been restored adjacent to the city's Multi-deity Temple 列圣宫. Few traces of the Chen Temple's original furnishings survive except for a large flag that bears the Duke's title, probably used for parades (Figs. 2, 3). Both the Chen and the Multi-deity Temples in Oroville were built in the 1870s.

The Gee How Oak Tin Family Association 至考笃亲, founded in Seattle in 1900, includes persons with the surnames “Chen 陈,” “Hu 胡,” and “Yuan 袁,” and still has 28 branches in many American cities. While not every branch seems to have paid attention to Suijing Bo, the ones in Portland and Seattle did. A brass censer bearing his name with several other dated objects in the handsome shrine still maintained by the GHOT in Portland indicate that he was worshiped by the GHOT from the founding of the Portland branch in 1904 down to the resent day.

Sometimes Suijing Bo's association with the Chens was not exclusive. A simple wooden building in John Day, Oregon, less than a hundred yards north of the Kam Wah Chong store, had little to do with the Chen clan and yet it was dedicated as a temple to the Duke (Fig. 6). Nothing from this late 19th century temple still exists except for a set of three wooden plaques bearing the temple's name. The plaques are stored in the Kam Wah Chong Museum (Fig. 7).

An equally simple building, probably from the 1880s, served as a Sujing Bo temple in Boise, Idaho. It was on the south side of Idaho Street between Seventh and Eighth Streets (Fig. 8). Judging from photographs published in the Idaho Daily Statesman, copies of which exist at the Idaho Historical Society, the interior of the temple was well furnished with fabrics, banners, and altar sets (Fig. 9).

1. Suijing Bo Temples and Shrines

3. Suijing Bo flag at Oroville

2. Two temples in Oroville, built in 1870s and reconstructed in the 1960s

4a. Gee How Oak Tin censer, Portland, with 1904 date.

7. "Suijing Bo" plaque, formerly over door or hanging from ceiling at former temple in John Day. Late 19th century

6. Former temple and store at John Day

It is worth noting that the early phase of temple-building in the Pacific Northwest often involved whole Chinese communities rather than clans or other limited groups. In later years, groups such as secret societies seem to have taken over the function of maintaining places of worship. In Boise, for instance, worshipers may have begun to shift allegiance after 1902, when the Chee Kung Tong 致公堂 (aka “Chinese Freemasons' Society” "Zhigong Tang") built a lavishly furnished temple to Guandi, the God of War, on the second floor of their new three-story brick headquarters.

8. Exterior of former Suijing Bo Temple in Boise

9. Interior of former Suijing Bo Temple in Boise

“Tianyun”--Secret Dates for a Revolutionary Cause

'天运' 年号背后的革命意识

Outside the front door of the Won Lim Temple 雲林庙 or"Joss House" in Weaverville, California, is a couplet carved on vertical wooden boards, with characters in dark blue against a gilt background [Fig. 1]. The boards bear a short, two-line Chinese poem conveying conventional good wishes. However, the left board also bears a date, “Tianyun jiaxu ...” The use of Jiaxu is not a surprise: it is a year in the Chinese cyclical dating system, equivalent to 1874 [Fig. 2]. The use of Tianyun, on the other hand, is astonishing. Meaning “Cycle of Heaven,” it appears in the position, right before a date, that in those days was reserved for the name of the current emperor. Using it implied that the writer was in rebellion against the rulers of China.

The Chinese imperial government did not take such matters lightly. The use of a Tianyun date, even in private, meant death for the writer plus, in all probability, his entire family. And yet in Weaverville the date was used publicly, on the front of a popular temple. What was going on?

Fig. 1. Boards with dedicatory couplets flank the door of the Won Lim Temple (or Joss House), Weaverville, California.

Lewiston's Beuk Aie Temple: Memorial to the Deep Creek Massacre?

噜士顿市重修北帝庙 - 记念蛇河华工浴血案?

Until now, no evidence has been found of the local Chinese community's reaction to the Deep Creek Massacre on May 25, 1887. Members of the community may have known about it within a few days of the event, as the first bodies of the murdered miners came floating past Lewiston. They definitely knew by June 11th when, according to the Lewiston Teller "a boatload of Chinamen came down the Snake River … and brought the news that another boatload of Chinese had been murdered about one hundred and fifty miles above here by some unknown parties" [Note 1] Those "Chinamen" were also miners,, led by Lee She [Note 1a]. The Teller subsequently reported that two men, a Chinese merchant [Lee Loi, from a settlement downstream from Lewiston] and J[oseph] K Vincent [a white Justice of the Peace], had traveled up the Snake from Lewiston on June 20th and brought back one of the bodies, which was buried in the town cemetery. [Note 2].

However, now it may be possible to recognize other evidence. This is due to the fact that the city's main Chinese place of worship, the Beuk Aie Temple, saw an unprecedented burst of activity in 1888-1890

The remains of the temple, now kept in the Center for Art & History at Lewis-Clark College in Lewiston, include seven dated objects, the only ones surviving from the more than 80-year lifespan of the temple between its founding before 1875 and its demolition in 1959. Significantly, five of the seven objects were donated over a very short period, between 1888 and 1890.

A. 1886, December (Guangxu 12th yr-11th mo) horizontal plaque. "惠及同人" [Extend your grace to our community]

B. 1888, November (Guangxu 14th yr-10th mo) Four unpainted boards with ink-written names of donors. "重修列圣宫梓里捐签芳名"

C. 1888, December (Guangxu 14th yr-11th mo) Pair of wood and painted glass lanterns

D. 1888, December (Guangxu 14th yr-11th mo) Pair of vertical plaques "帝德远涵. 神灵常显" 对联

E. 1889, February (Guangxu 15th yr-1st mo) horizontal plaque. "帝德广被" [Your imperial virtue spreads far and wide]

F. 1890, March (Guangxu 16th yr- 2nd mo) horizontal plaque. "佑我平安" [Keep us in Peace]

G. 1905, March (Guangxu yiji 乙巳cyclical date) horizontal plaque. (not shown here) "阿堵有神" [The Spirit is here]

The middle five are the important ones in terms of the Massacre. Each represents significant contributions to the temple by either a few wealthy donors (in the case of C, E, and F) or numerous poorer community members (in the case of B and D). They represent, in fact, just about the only contributions during the temple's entire history of which the memory has been preserved. Hence they must commemorate something. But what?

D. 1888,top of plaques with couplet

光绪十四年岁次戊子仲冬旭旦

帝德远涵濡恩流异域

神灵常显赫光耀蛮邦

沐恩弟子噜士顿梓里敬送

Priscilla Wegars has indicated, plausibly, that the contributions must relate to a rebuilding of the temple. In an email to the editors she quotes from the following article, also from the Teller: "The Chinese of this city have erected a new Josh House [i.e., temple] in the place of the old one, and have otherwise improved the property." [Note 4]

The timing is about right. It is plausible that it took a while for the full horror of the situation to sink in, and after that for members of Lewiston's Chinese community to understand the extent of their spiritual as well as physical vulnerability, dwelling in the town where so much death had washed up and floated by. It would have been a natural reaction for them to begin raising funds for re-decorating the temple and add new furnishings, perhaps dedicated especially to the Northern God who controlled the deadly river, and for Chinese in other places to send contributions to express their concern.

We have no evidence for this except the dated objects and the donations they commemorate. Only one of the inscriptions on the objects (see "A Heartfelt Plea", below) may allude to the massacre. And yet we find it hard to think there was not a close connection. Local Chinese must have experienced profound psychological reactions, although unnoticed by to the white media. There must have been sorrow and fear, not just of further violence but of vengeance by the spirits of the unburied dead. The temple's gods would have been their main defense.

The editors owe thanks to the following staff of the Lewis-Clark Center for Arts & History: Ellen Vieth and Ray Esparson for showing the Beuk Aie objects to us and to Kathy Martin for making the needed arrangements.

Note 1: Lewiston Teller 1887-06-16, quoted by Nokes, p 26.

Note 1a Chang Yen Hoon t0 Sscretary of State Bayard 1888-02-16. Papers Relating to the Foreign Reltions of the United States ...1888. Govt

Note 2: R. Gregory Nokes, Massacred for Gold: The Chinese in Hells Canyon. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 2009, pp 26-7; 66-68.

Note 2b Chang Yen Hoon t0 Sscretary of State Bayard 1888-02-16. Papers Relating, etc..

Note 3: Nokes, p 70-76

Note 4 Lewiston Teller 1888-12-27, p 3:

Note 5 Priscilla Wegars, Chinese at the Confluence: Lewiston;s Beuk Aie Temple. Lewiston, ID: Lewis-Clark Center for Arts & History, 2006

So the Chinese of Lewiston, of whom there were several hundred, definitely knew about the massacre, and the involvement of Lee Loi and another local Chinese named Chea Tsze Ke [Note 2a].meant they were kept abreast of many horrifying details. Later that year they would be at least tangentially involved in the investigation led by Vincent and financed by the Sam Yup Association in San Francisco through that city's Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association. In early 1888 they might have heard about the official protest lodged by the Chinese government at the offices of the U.S. Secretary of State in Washington[Note 3]. And that was it. Until recently, those facts and surmises were all that historians knew about the reaction of Lewiston's Chinese.

Later version of Beuk Aie Temple, after 1890

噜士顿北帝庙

A. 1886. Dedication plaque "惠及同人"

[Extend your grace to our community]

from 17 donors, 16 Wu and 1 Liu:

伍文-- 大. 羡. 宏. 晋.

伍学-- 玲. 泮. 锐. 仕.

伍龙-- 得. 基.

伍成文, 伍钜荣 , 伍源荣

伍炳扶, 伍于登 , 伍社宇, 刘朝彦

B. Left: 1888, 3 of 4 boards recording donor's names and amounts given - 549 individuals and 19 businesses. A total of $926.75 was raised. Right: detail.

重修列圣宫梓里捐签芳名

D. 1888, bottom of plaques with couplet.

D. 1888 date on plaques with couplet

F. 1890 Dedication plaque "佑我平安"

[Keep us in Peace]from Lin Jiu 林九

E. 1889 Dedication plaque "帝德广被"

[Your imperial virtue spreads far and wide]from 17 Lee family members. Six had a personal name "Loy". Could one of them be the Lee Loy who joined the investigation of the massacre?

李祖撰, 李祖在, 李成安, 李崇话, 李年亨, 李来珍, 李广明, 李叶全, 李乙有, 李熊发, 李进来, 李记来? 李沾来, 李嘉来, 李春来, 李O来

In her book on the Beuk Aie temple [Note 5], Wegars notes that the community had been forced to rebuild it twice during its history, once in 1883, due to a major fire and again after 1890 when its old site was being washed away by the Clearwater river. However, in 1888 there was no such physical reason for rebuilding the temple. Hence we wish to suggest that the reason was not physical but social and spiritual: an outpouring of community support, and perhaps apprehension as well, in response to the 1887 massacre.

C. 1888, one of pair of lanterns with painted glass panels, from 7 donors., including two (named Wu or Ng) whose names are on the 1886 and 1888 plaques

painted glass lantern with date

| ||||

| ||||

Who Were the Donors? 善长芳名说开来

With almost 550 donors who came up with $925.75 for the temple, one can say with confidence that just about every Chinese in the greater Lewiston area gave, considering that in 1890 there were only about 2000 Chinese in the whole of Idaho state.

The most generous donor was a Mr. Zhou 周 [aka Chow] and a business; each gave $15. The smallest donation amount was $0.25, made by 7 individuals. The majority gave $1 (51%), $2 (14%) and 50 cents (12%).

Only five Zhous were listed on the donors’ board. Altogether the temple received donations from members of 97 different clans, 95 donors were named Li 李 [or Lee], 92 named Huang黄 [or Wong, Wang], 84 named Wu 伍 [or Ng, Eng, Ing], 45 named Lin 林 [or Lum, Lam], and 28 named Liang梁 [or Leong]. But in terms of generosity the Wus took the lead, contributing $157 (17%) of the total sum, with the Lis trailing behind at 16%.

The nineteen businesses may have been groceries, restaurants, herbal stores, gambling halls, or even brothels. Seven businesses called themselves “guan”, or gallery; a term generally used for service providers. One such had a distinctly feminine name, Xing-xiang-guan 杏 香 馆 [Fragrance of Apricot Gallery]. This is likely to have been a brothel. Moreover, six ladies on the donor list appeared without family names, with contributions ranging from $5 to 50 cents. As suggested by Wegars (2006: 38), they may well have been prostitutes

A Heartfelt Plea

Only one of the inscriptions may refer to the massacre: the board given in 1890 by Lin Jiu 林九 [or Lum Gow]. He had already donated four dollars in 1888 but seems to have felt this was not enough. Fourteen months later he gave a gold-on-green board with this message: "Keep us safe and grant us peace."

The Sze Yap temple at Pine and Kearney Streets seems to have been identical with the Guandi temple later owned by the Kong Chow Association at that location. Regarded by San Francisco Chinese as a particularly sacred shrine, the temple remained at Pine and Kearney for more than a hundred years, having been rebuilt in the same spot after the earthquake of 1906. In 1977 it was moved by the Kong Chow Association to the top floor of a building on Stockton Street, The oldest object in the present temple is a bell which, as noted elsewhere on this page, only dates to 1909. However, the Association's ownership of the Guandi temple goes back to 1866, the time of the breakup of the original Sze Yap huiguan. That was when Kong Chow inherited the temple built by the Sze Yaps in earlier years [Him Mark Lai, Becoming Chinese American, 2004: p 42].

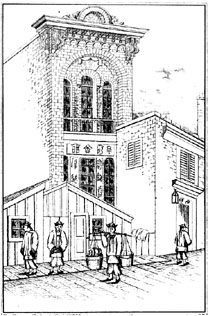

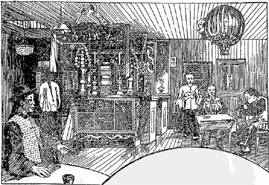

As far as we, the editors, know, this is the first image of religious practice among overseas Chinese to have been published anywhere outside Asia. It is surprisingly good. As was not always true of newspaper graphics in the 19th century, the details of this picture are convincing enough to show that the artist had visited and made sketches in an actual temple. Was that temple, the one the artist visited, the same as the one described in the article? We do not know.

1857: The Earliest Picture of an American Chinese Temple

最早华人庙宇插图

From the Children's Missionary Newsletter, January, 1857

At least two Chinese temples in San Francisco, those of Tin How (Pinyin: Tian Hou) and of the Kong Chow Association, claim to go back to the late 1840s or early 1850s. As indicated above, those claims, based on later assertions by people who did not themselves see the temples back in the 1840s or 1850s, are none too solid. The earliest first-hand evidence we have seen is an 1853 article in the Alta California (1853-07-15) that notes the founding by the See Yup Society of a Chinese "church" on the corner of Kearney and Pine Streets in San Francisco. Considering that the "See Yup" (= Sze Yap, SIyi or Four County) Company was by no means a Christian group, it seems likely that the "church" was the temple of a traditional Chinese religion, probably folk Daoism.

"The large tablet over the door tells, if English alphabetic letters be employed for the

Chinese characters, the name of the company:

"The two perpendicular inscriptions on either side are poetical lines. They read as follows:

"The two smaller lines on either board contain the words, "Set up on a fortunate day of the

8th month, 2nd year of the Emperor Hienfung [pinyin: Xianfeng]" -- "Carved by Fan Yi"

An Even Older Temple Inscription

阳和会馆-目前记录中最早神盦

Each of the main regional associations or huiguan that made up San Francisco's so-called Six Companies, had a large shrine or small temple on an upper floor. Thus, the inscribed boards that once existed in front of the Yeung Wo Association, located on the northern edge of Chinatown, count as temple inscriptions

The Yeung Wo Association, one of the original Six Companies, was founded in 1852 by immigrants from Heung Shan (now Zhongshan) and several other counties at the mouth of the Pearl River. It seems to have survived without major conflicts down to the present day. In 1870 William Speer, who had been a missionary in Chinatown for almost twenty years, tried to correct the false image of the Six Companies being propagated by anti-Chinese agitators. To do this, he described the organization of a single "company" or huiguan, that of the Yeung Wo.

His detailed critique of the notions of white racists who insisted, on no grounds at all, that the Companies were profit-making institutions that dealt mainly in prostitution, gambling, opium, and slavery, is important but not germane to the present subject.

However, one of his details is indeed germane. By an extraordinary stroke of luck for us, Speer chose to transcribe the dedicatory plaques at the door of the huiguan's main building

The Ning Yeung huiguan headquarters, San Francisco, from Speer 1870. The Yeung Wo building may have been quite similar.

Thus we have the complete texts of all three boards, transcribed in 1870 (or in 1855--see Note 3) by an old Chinatown hand who was a competent linguist. His transcription is in Cantonese or Zhongshanese. What interests us most are several words on one perpendicular board, probably that on the right facing the doorway. These constitute a Chinese date: "8th month, 2nd year, Xianfeng reign," equivalent to September-October 1852. That makes it by far the earliest inscription that we know of from anywhere in Chinese America.

What happened to these boards, the ones from the Yeung Wo headquarters? They must have been destroyed in the 1906 earthquake, if not before. However, the Chinese version can be reconstructed with fair certainty. It would be quite possible, some time in the future, to remake the original sign boards and, perhaps, to put them up at the door of the present-day Yeung Wo Benevolent Society.

The Chinese characters for the perpendicular inscription, a poetic couplet, can be reconstructed as follows. The romanized reading is in Mandarin, corresponding to Speer's Cantonese/Zhongshanese

10/22/2010 The editors wish to thank Phil Choy of San Francisco, the leading expert on historic images of American Chinese life, for identifying the huiguan in the above picture and for correcting a serious misconception of ours by pointing out that the Yeung Wo texts were published by Speer in 1870, not, as we had thought, by S. Wells Williams in 1883.

Although unfamiliar to most Americans, the North God has long been a major deity in the eyes of Chinese, important as a general protector and as a controller of fires and floods. Not only was he once worshiped everywhere in China but he was also the main Daoist deity of the imperial household, his temple in the Forbidden City, the Qin'andian, being the northernmost of the North-South line of major palaces that represented the axis of the universe.

He went everywhere early Chinese immigrants went. In North American Chinatowns he was known by at least two names: as the "North God" (北帝 --Beidi in Mandarin and Bok Dai, Pak Tei, Pak Tie, Bok Kai, Buck Eye, and Beuk Aie in Cantonese and/or Taishanese), and, more formally, as the "Lord of the Dark (or Somber) Heavens" (玄天上帝 -- Xuantian Shengdi in Mandarin and Yuan-tian-siang-dai in Cantonese). Modern martial artists revere him too. They call him "Dark Warrior" (玄武 Xuan Wu) or "True Warrior" (真武 Zhen Wu),

1866. Marysville, CA. The Bok Kai Temple 北溪庙 has an inscribed board dated to Tongzhi 5, or 1866. The formal name of the temple was not Bok Kai but "Liet Sing Gung" [Leishenggong}, "Multi-Deity Temple," which appears on several signboards and hangings. However, most multi-deity temples on this side of the Pacific included the North God. He probably was present in the Marysville temple in 1866, if not before A recently made sign over the door of the modern temple reads "North River God." Whether that is an old name is unclear [Note 1].

1871. San Francisco. "Pak Tie" is one of three gods whose statues were the focus of worship in the main central hall of the newly opened Tung Wah Miu [pinyin: Donghuamiao], "the Temple of Eastern Glory", on Dupont [Grant] Street between Washington and Jackson (Alta California 1871-02-10 & 12) . The other gods in the center hall were reported to be Quan Tie [pinyin: Guandi], the God of War) and Hung Sing (God of Water), and there were other deities in other rooms. According to Alta's reporter, the temple belonged to one of the Six Companies. A photograph by Edward Muybridge, taken between 1870 and 1875, shows an altar in a temple that is probably the Tung Wah Miu.

1874. Weaverville, CA. The Won Lim Temple, with several inscriptions dating to Tongzhi 13th year, also has inscriptions showing that it was a multi-deity temple. One of the original featured deities may have been Beidi, whose image is currently one of the three on the main altar [Note 1a]. By 1874, and perhaps earlier Won Lim was sponsored by the Hongmen/ Chee Kung Tong secret society. This does not seem to have kept most Chinese from worshiping in it.

<1875. Lewiston, ID. A Multi-Deity Temple or "Liet Sing Gung" (列圣宫, pinyin: Leisheng- gong) was founded. It survived until 1959.. Bok Kai/Beidi was probably one of the original deities. His name appears on a later five-deity plaque that stood behind the central altar. The others are Guandi, Guanyin, Toy Guon (riches), and Wah Ho (medicine) [Note 2]

1876 -1885 San Francisco. At least four early sources, copying from each other, mention a "Eastern Glorious Temple" founded by a well-known herbal doctor named Lai Po Tai. The temple has three idols in the central hall, including "the Supreme Ruler (or God) of the Somber Heavens" [Note 3]. This one may not be the same as the 1871 Tung Wah Miu

1877. San Francisco. The wife of a New York magazine publisher visited a temple on Dupont Street that included a figure of the God of the Somber Heavens "sitting in a tree [!] and controlling fires and floods" plus many other deities [Note 4]

1880. Marysville, CA. A temple called "Bok Ky" and at the present location of the present Bok Kai temple,was mentioned in a local Marysville newspaper [Note 5]. Local Chinese may have begun calling the temple Bok Kai well before this date.

1889. San Francisco. The Chronicle (1889-09-15) listed "Hieng Tieng Siang Ta, the Supreme Ruler of the Somber Heavens" [pinyin: Xuantian Shengdi] as one of the locally worshipped deities. No specific temple or location was given.

<1890. By now, Lewiston's Multi-Deity Temple, has come to be called colloquially "Buck Eye" or "Beuk Aie" Temple 噜士顿北帝庙.

1892. San Francisco. Masters, the most authoritative 19th century source for Chinese religion in San Francisco, stated that there was a "Temple of the God of the North Pole and the Azure Heavens" on Waverly Street near Clay Street. Masters listed this one separately from the Temple of Eastern Glory at 35 Waverly Street, which we know from other sources (see above) treated Beidi as one of the temple's principal deities [Note 6]

Note 1. The inscription over the temple door reads "Bok Ch'i Miu" (pinyin: Beiqi Miao) or North River (God) Temple. Paul Chace ("On Dying American," in Sue Fawn Chung and Priscilla Wegars, Chinese American Death Rituals, 2005: p 58. Altamira Press) joins the noted scholar of Chinese folk religion, Wolfram Eberhard, in suggesting that the main diety may not originally have been the North God but another local deity named for the river. This may be so. However, it is clear that (1) the original temple was of the multi-deity type, and that (2) it was called "Bok Ky" as early as 1880 [Note 5].

Note 1a. According to The Home Missionary, (Vol 50, 1878: pp 15-6), the Weaverville temple burned to the ground in the mid-1870s and had new statues of deities made (by a San Francisco-based specialist, of local clay) shortly afterward. The Beidi statue shown here could be one of those sculpted in the 1870s.

Note 2. Priscilla Wegars, Chinese at the Confluence: Lewiston's Beuk Aie Temple, 2000: pp 12-13, Lewiston.

Note 3. (a) B. E. Lloyd, Lights and Shades in San Francisco, 1876: p 274, San Francisco; (b) Rev. Otis Gibson, The Chinese in America, 1877: p 734, Cincinnati; (c) George A. Sala, America Revisited, vol 2, 1882, pp 264-5, London; (d) Report of the Royal Commission, 1885: p 368, Ottawa

Note 4.. Mrs. Frank Leslie, California, A Pleasure Trip, 1877: p 151, New York & London.

Note 5. Marysville Daily Appeal 1880-03-23, quoted by Chace, p 58 [see Note 1 for reference]

Note 6. Frederic J. Masters, "Pagan Temples in San Francisco," The Californian, vol 2, 1892: p 740.

Marysville's Bok Kai Temple

on Bomb Day, 2008

Unnamed San Francisco temple from Lloyd 1876; One of the four deities in the center is "the God of the Sombre Heavens"

Plaque with names of Beidi and

4 other deities, Beuk Aie Temple,

Lewiston. Photo from Lewis-

Clark Center for Arts & History

Statue of Bei Di, Won Lim Temple, Weaverville. Probably 19th century.

Muybridge photo with Beidi behind altar, San Francisco, 1870-75,

Main altar at Bok Kai Temple, Marysville. Beidi is 4th from left

Deity names from altar at Bok Kai Temple; Beidi is included.

Deity names including Beidi, from Muybridge photo, 1870.

Cheung Chau Pak Tei Temple, Hong Kong. From Wikipedia

The North God in North America 飞越太平洋的北帝

Although many temples were dedicated to him in China, including the one in the Forbidden City and the Hong Kong example shown above, in North America he did not have his own place until late in the 19th century. Almost all temples where the North God was worshiped were originally of the leishenggong or multi-deity type, which he shared with other popular gods and deified humans. In time some of those temples, like those in Lewiston and Marysville, started to be named after him, but even then the temples' formal names were different. The one in Lewiston continued to be called "Multi-Deity Temple" throughout its history

The Kong Chow Building in San Francisco – Prestige from Diplomats' Calligraphy 三藩市1909年重建岡州会馆 - 门楣显赫

Destroyed in the earthquake and fire of 1906, the headquarters and temple of the Kong Chow Benevolent Association were rebuilt in 1909 at their previous location on Pine Street [see below, Oldest Temple]. The temple, now located above a post office on Stockton Street, continues to be one of the most popular Daoist shrines in California. An article on the shrine itself will be included on this page in due course. An article on the "Associations" page presents dedication plaques from the temple's street-level entrance; those plaques represent the more secular side of the Association's history.

Apparently, back in 1909, the elders of the Association used the rededication of their new building as an opportunity to ensure the goodwill of top-ranking Chinese diplomats, who in those days had real power over American Chinese. One of those plaques is shown here. The others may be seen in the Associations page article.

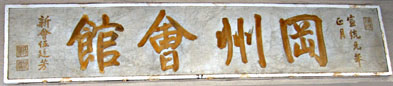

Lintel “Kangzhou [Kong Chow] Huiguan [Association]” in gold on white marble, 1909. Calligrapher: Wu Ting Fang of Xinhui, 2 seals.

The most important of the plaques contains the calligraphy of the accomplished diplomat Wu Tingfang. A native of Xinhui, one of the several Taishanese-speaking counties from which the Association's members came, Wu may have been the best-known and respected diplomat in the Qing dynasty government, noted for his excellent English, witty interviews and lectures, and able defense of his nation's interests. Attached to the Chinese foreign service since the 1880s, he served as the Chinese minister plenipotentiary (i.e., ambassador 清朝驻美国使臣) to Washington from 1897 to 1903, and again from 1909 to 1910. He visited San Francisco in 1878, 1897, 1903, and 1909. The Kong Chow Association gave a banquet for him in 1897 and must have given one to his wife as well when she stayed in San Francisco for several months in 1901. San Francisco's Chinese may have felt they owed a special debt to Wu because of his efforts in 1897 to settle once and for all the bloody conflict between the Taishanese-apeaking Sze Yup ("Four County") and the Cantonese-speaking Sam Yup ("Three County") factions in Chinatown.

For more on these diplomats' plaques, click here.

Wu Ting Fang 伍廷芳

San Francisco 1897.

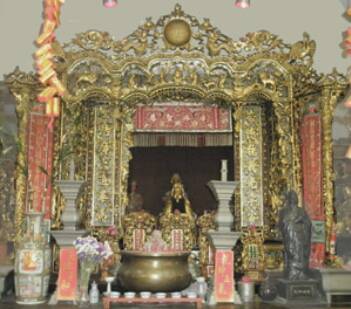

Closeup of the CCBA shrine, with Guandi 关帝 (center) and a modern statue of Confucius (right)

Pewter censer in today's CCBA shrine. It's "wings" have now been broken off. The characters at its waist read "Lieshenggong". It was made in 1885, a gift from the Ma Clan Association.

For more on Victoria's CCBA and on the splendid dedication boards that decorate it, click here.

Note 1. Robert Amos and Kileasa Wong, Inside Chinatown, Ancient Culture in a New World, Touchwood Editions, 2009.

Note 2. David Chuenyan Lai, Chinese Community Leadership: Case Study of Victoria in Canada. World Scientific Publishers, 2010, pp 40-42

Note 3. This photos are from the collection of Bon Lee of Victoria. He got them from his father, the distinguished historian David Lee (not to be confused with the equally distinguished David Chuenyan Lai, also a Victoria historian).

Note 4. Victoria British Colonist 1909-10-12, p 15.

David Lai points out that in 1885 "the CCBA board directors erected a new temple called the Palace of Sages (Liesheng Gong) in the middle room of the top floor [of the just-completed CCBA building] as a source of income." [Note 2] The temple housed images of three deities: the God of Wealth, the God of Righteousness, and the Queen of Heaven (i.e., Tianhou/Tinhow, no longer present) . Each year the CCBA accepted bids for the management of the temple that brought in an annual income of more than $1000. Evidently the temple was popular and, due to offerings, profitable.

According to an article on April 4, 1885 published in British Colonist, the temple was originally independent. It was taken over and reconstructed in 1885 by the newly formed Chinese Benevolent Association, which built its new headquarters on the same spot.

The altar shows that Victoria's Temple of Many Gods was wealthy. It may well have been the most elaborate and costly in the Pacific Northwest. This makes sense in view of the prosperity of Victoria's Chinese businesses in the 1880s, when they were not only supplying contract labor and services to a large population of gold miners but also doing a thriving trade in opium, The CCBA's handsome congratulatory signboards, described elsewhere on this website, also show the wealth of the community in those days. The fact that the signboards bear the same date as the temple's pewter censers, 1885, might be taken as proof that the temple was part of the celebration for the newly established CCB Association.

But the relationship between the temple and the CCBA was not always in harmony. Their conflict is illustrated by a curious incident that occurred in 1909, According to the Colonist newspaper, the merchants of Victoria's Chinatown, who in those days were more or less identical with the membership of the CCBA, made an effort to close all four local Daoist temples ("joss houses"), claiming that"they were relics of the old superstition and out of keeping with the new China."

The merchants announced that a vote would be held at a meeting in the new Chinese school--the same building that now houses the shrine. However, the planned vote was canceled permanently when a mob of 300 Chinese workers entered the school and smashed the ballot boxes, shouting that "they had paid for the upkeep of the Joss-houses and proposed to maintain them, and they would never consent to the gods being cast out."[Note 4]

The other three CCBA in the Northwest must have had better luck in imposing a new outlook. Today, none of other CCBA in the region retains their original or affiliated shrine/temple.

The CCBA's Shrine in Victoria: Was It Originally Theirs?

维城.域多利关帝神盦原属列圣宫? 还是中華會館?

Right: CCBA shrine now in the top floor of the Chinese Public School, Victoria. Below: An earlier photograh of the shrine in situ [Note 3]

版权 Copyright is free for non-profit use: click here for more info

The fact that buildings dedicated to Suijing Bo could stand alone, rather than as shrines in buildings with more general functions, is likely to reflect support from a community wider than only Chen Association members. Outbreaks of disease, perhaps tuberculosis, may explain the Duke's popularity.

Yet another appearance of Suijing Bo was in a temple primarily dedicated to Kwan Yum (pinyin Guanyin) on Spofford Alley in San Francisco. Masters mentions this in his 1892 article, translating his name as Grand Duke of Peace

The editors wish to thank Christine Sweet, curator of the Kam Wah Chung Museum in John Day, for showing them the Suijing Bo plaque in the Museum's collection. A full reference to Masters' 1892 article can be found in Note 6 of the North God section on this page.

Suijing Bo and Gee How Oak Tin Benevolent Associations 绥靖伯与至孝笃亲公所

5a. Gee How Oak Tin altar, Seattle, with 1903 date

5c. "The spirit tablet for Chen Zhongzhen of the Imperial auspicious titled Suijing Bo" .

One of the altar tablets in Seattle's Gee How Oak Tin

5b. The name of Suijing Bo is seen on this large pewter censer.

In Seattle, Suijing Bo's title is seen on two ritual objects on the altars of the shrine of the Gee How Oak Tin Family Association on 7th Avenue, International District. The first one is the central censer of a 5-piece altar set 五供, which is engraved with the duke's title (Fig. 5b). The second ritual object is a spiritual tablet that bears the duke's full title and name (Fig. 5c).

5d. Gee How Oak Tin Building, Seattle. The altar is in the room behind the recessed balcony on the 3rd floor

Illustrated San Francisco News, 1869. From LoC "Amer. Memory"

"Sze-Yap Temple," San Francisco, 1857

The same temple, San Francisco, 1869

Even this does not constitute full proof of the presence of traditional Chinese worship, however. For that we must wait another three years, when an unnamed San Francisco newspaper, probably in 1856, published a picture of a newly opened temple of the "Sze-Yap" Company (which probably was the 1853 temple at Pine and Kearney), dedicated to Ching-Tai, "a famous Chinese soldier" whose "face is of the brightest red colour." The picture was picked up and republished in January 1857 by a periodical for young Christians, the Children's Missionary Newspaper, adding the information that Ching Tai "lived about 1500 years ago and conducted himself so bravely that the Chinese have worshipped him ever since." Ching Tai's red face and date indicate that he was Guandi, the God of War, under another name.

The same image, recognizable by the triangular flames that radiate from the deity's body, appears in a later picture from another San Francisco newspaper. The temple around he image seems to have grown between 1857 and 1869.

金山西北角 - 华裔研究中心

A temple bell in the same shrine is earlier than the GHOT itself. Bearing a cast-on inscription dedicating it to a Suijing Bo Temple in 1888, the bell shows that such a temple did exist in or near Portland in the nineteenth century. It may have been a private chapel for the Chen family or, alternatively, a temple for the whole community.

4b.Suijing Bo temple bell with 1888 date

The only known Chinese Temples -- "Joss Houses" -- in Seattle before modern times

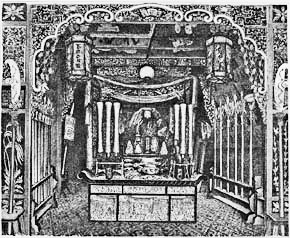

No one in present-day Seattle Chinatown remembers seeing a publicly accessible Daoist (Taoist) temple or shrine, and yet such institutions did exist there. The only picture we have found of the interior of such a shrine, dated 1902, is shown below.

Although called a Joss House by the Seattle Times [1902-01-18, p 17), this appears to have been not an independent temple but a publicly accessible shrine within a space belonging to a secular organization. According to the accompanying article by a Times reporter, in 1902 Seattle had two joss houses "in an alley off Washington Street, between 4th and 5th Avenues":

"One of the joss houses in Seattle is called a free mission [sic] establishment. There are no charges to the worshippers. The door is seldom locked and they come and go at will. Some of the Chinamen call this free mission Chen Gong Tong [sic]. Next door and a flight further up is Hip Sing Tong perhaps the name of their joss. It is more in the nature of a swell or select club, although there are none to say nay to the comings and goings. This last joss house is smaller but more elaborate, possessing mahogany furniture, and exhibiting an array of altar trappings of more apparent value than the one below. . ."

The reporter may have had trouble reading his own notes. He wrote "free missions" instead of free masons, and "Chen Kong Tong" instead of Chee Kung Tong. However, he is clear that the two joss houses belonged to separate organizations, the Chen Kong Tong and the Hip Sing Tong, that the latter was smaller and richer, and that its membership was more "select." All this makes sense. We know from other newspaper articles that the Hip Sing and the Chinese Masons met in the same place, "next to the old joss house," (Times 1901-04-03, p 2); that the Chinese Masons' joss house was at Fourth and Washington (Times 1901-05-08, p 5); that a joss house at this location, next to the Wa Chong Building, was called "the old joss house" (Times 1902-02-06, p 7); that a year later at least one of the joss houses was moved from the Wa Chong Building, which was due to be torn down for a planned Great Northern Railroad station, to "new quarters on Main Street between Fifth and Sixth Avenues South" (Times 1903-01-16: p 10); that one of these relocated joss houses belonged to the Hip Sing (Times 1903-01-20, p 4); and that the Chinese Masons kept their joss house at the Fourth and Washington location for several more years (Times 1905-05-08, p 5).

Which joss house is shown in the above drawing? Our best guess is that it was the Hip Sings', before moving to Main Street. The association moved again after that and is now located on 8th Avenue near the corner of King Street. Bob Fisher of the Wing Luke Museum tells us that a number of years ago the shrine area of the Hip Sing building was burned and a few surviving fragments donated to the Museum. We do not yet know is any of those fragments resemble the altar furnishings in the 1902 drawing.

Seattle Shrine, probably of the Hip Sing Tong, in 1902. .

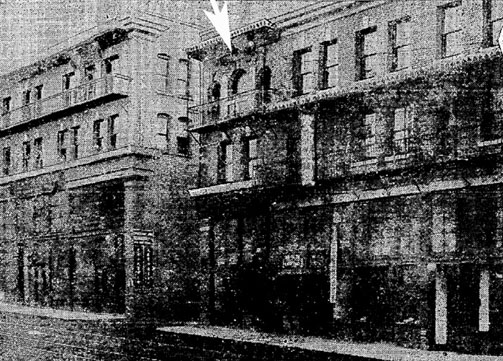

The only other published image of a supposed Seattle joss house that we have seen appeared in the Seattle Times in 1911 (Nov. 26, p 41):

As may be seen, the picture is not a good one. It shows the corner of one of the Kong Yick buildings, completed in the previous year, on King Street between 8th and 7th Avenues (the Wing Luke Museum now occupies the building on the left). The arrow points to a balcony, now gone, in front of rooms that currently belong to an important four-clan association, the Lung Kong Tin Yee. It seems quite possible that the Lung Kong Tin Yee Association occupied the same space in 1911, and that the so-called "joss house" was the Association's private, not public, shrine.

Lung Kong Tin Yee "Joss House," Seattle, 1911

This page was last updated: August 30, 2018

In 1917, the Bing Kung Tong dedicated a new shrine within its building at 8th and King Streets. Said to be "the finest temple in the country," it was described by the Seattle Times (1917-02-26) as the "last word in opulence of decorative work that includes tapestries, richly-inlaid woods, fine porcelain and artificial flowers ... There is only one other Chinese Masonic temple approaching the Seattle shrine, and that is in San Francisco."

The editors can now confirm that much of this decorative work survives and that it is.indeed fine. However, it is in Euro-American rather than Chinese taste. Like the equally handsome Hook Sin Tong meeting room in Victoria, it shows that some Chinese organizations in the Northwest accepted Western aesthetic norms as early as the 1900s and 1910s.

(UNLESS OTHERWISE STATED ALL DATA ON THIS PAGE COMES FROM THE EDITORS' OWN RESEARCH ON PRIMARY SOURCES & ARTIFACTS)

Oct 21, 2012. Peter Manseau has just sent us the following article from the San Francisco Whig, as reproduced by the Salem [Massachusetts] Register. Describing the dedication of the Yeung Wo temple in some detail, it is among the earliest surviving records of American Chinese religious activity.

The Whig's reporter seems not to have fully understood what he was seeing. His mention, twice, of Chinese "priestesses" is a case in point. Chinese temples did not have priestesses. While the so-called high priest may well have been a real Daoist, it seems more likely that the other participants were actors from an opera troupe. In China, opera performances would normally have accompanied major temple ceremonies, and a number of the male actors would, as was customary, have appeared in female costumes.

Note 1 Him Mark Lai, Becoming Chinese, 2004, p 41, Walnut Creek, CA: Altamira Press

Note 2 William Speer, The Oldest and the Newest Empire: China and the United States, 1870: p 556. Hartford: S. S. Scranton.

Note 3 Yong Chen (Chinese San Francisco, 2000, p 72) says that part of the Yeung Wo inscription appeared in William Speer's Chinese-English newspaper, The Oriental, in 1855

Note 4 Before the transcontinental railroad and telegraph, it would have taken about two months for a copy of the Whig to reach the Register's editors in Massachusetts. Hence, the Whig's original article must have appeared in October or September, 1852. The relevant issue of the Whig still exists, in the N. Y. Public Library and the U. C. Berkeley Libraries. It has not not been digitized yet.

崇光咸萬里 (chong guang xian wan li)

瑞氣播同寅 (rui qi bo tong yin)

An even older inscription exists in the Temple of Many Gods (Leishenggong) in Oroville. One of its donor boards seems to be earlier than any temple object in Marysville. Though hard to see in situ, the board was well photographed by the University of California-Berkeley Library team that catalogued the temple's contents in 2000 (note 2). The board looks like this:

The date on the board is Tongzhi, 2nd year, or AD 1863. This makes it three years older than the one in Marysville and, as far as we know, the second oldest surviving Chinese North American religious object anywhere (note 3).

Donor plaque with 1863 date, gilded and painted wood, from Oroville Temple. Credit: Bancroft Library, U. of California-Berkeley and City of Oroville

Location

BC Vancouver. Hongmen Association

BC Vancouver. Hongmen Assn.

BC Vancouver. CCBA/Chong Wa Assn.

BC Victoria. Tam Kung Temple[1]

BC Victoria. Dart Coon Club

CA, Marysville. Bok-Kai Temple [2]

CA, Oroville. Oroville Museum

CA, Oroville. Oroville Museum [3]

CA. SF. Kong Chow Association

CA. SF. Kong Chow Assnn[4]

CA. SF. Lung Kong Tin Yee Assn

CA. SF. Lung Kong Tin Yee Assn

CA. SF. Tin How Temple [5]

CA. SF. Tin How [Tianhou] Temple

CA. SF. Tin How Temple [6]

CA. SF. Tin How Temple [7]

CA Merced, Suey Sing Association

ID. Boise. Idaho State Historical Museum

IL Chicago. Hongmen Chee Kung Tong [8]

IL Chicago. Hongmen Chee Kung Tong [9]

IL Chicago. Moy’s Association [10]

IL Chicago. Moy’s Association

MA Boston. Gee How Oak Tin Assn.NE

MA Boston. Gee How Oak Tin Assn.NE

NY New York. Eng Suey Sun Assn.

OR Portland. Gee How Oak Tin Assn.

OR Portland. Gee How Oak Tin Assn.

OR Portland. Gee How Oak Tin Assn.[11]

OR Portland. Gee How Oak Tin Assn.

OR Portland. Bing Kung Tong

WA Seattle. Hoy Sun Ning Young Assn

Peru, Lima, Panyu Assn. Temple

Peru, Lima, Panyu Assn. Temple

Peru, Lima, Panyu Assn. Temple

CA, San Jose, Ng Shing Gung Temple

CA, Fresno, Historical Society

CA, Oroville, Chen Suijing Bo Temple

CA, Oroville, Lie Shing Gong Temple

CA, Marysville, Bok Kai Temple

CA, Marysville, Bok Kai Temple

CA, Weaverville, Won Lim Temple

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

Object

altar table façade. shrine niche

shrine niche/hall

altar table façade.

shrine niche

boat-shaped hanging

sedan chair for deity

boat-shape hanging

shrine niche

altar table façade.

shrine niche

altar table façade

shrine frame

shrine niche

boat-shaped hanging.

altar table façade

altar table facade

wall hanging.

altar table façade.

shrine niche

altar table.

shrine niche

.

shrine niche

altar table façade.

shrine niche

altar table facade.

altar table façade.

boat-shaped hanging.

shrine niche

shrine niche

altar table facade

altar table facade

boat-shaped hanging

shrine niche

altar table facade

altar table facade

altar facade, damaged

altar table facade

altar facade1, damaged

altar table facade 2

altar table facade

Maker, Date

San You 三友. 1906.

Xu San-you 许三友. 1906

Shi Tai 时泰 n.d.

Xu San-you 许三友. 1898.

Xu San-you 许三友. 1907

.

Xu San-you 许三友. 1890.

Yi Chang 怡昌. n.d.

Xu San-you 许三友. 1904.

Shi Tai 时泰. 1911

Huang Fu-xing 黄福兴. 1909.

San Xing 三兴. 1911

Shun-chang-tai 顺昌泰

San Xing 三兴. 1911.

Shi Tai 时泰. 1911

Zhu An竹安. 1911.

Xu San-you 许三友. 1911

Foshan, Zeng Tai-yuan 曾太元 1875

Zhao San-you 赵三友. 1906

Shi Tai 时泰. 1894.

Shi Tai 时泰. 1894.

Chang Xing 昌兴. n.d.

He Cai-ji何财记, n.d.

Long Chang 隆昌店. n.d.

Shi Ta 时泰. n.d.

He San-you the Original 何三友老店. n.d.

Shi Tai 时泰. 1904.

Shi Tai 时泰. 1904.

Shi Tai 时泰. n.d. 1904?

Shi Tai 时泰. n.d.

Shi Tai 时泰. 1904.

Xu San-you 许三友. n.d.

Xu Sanyou 许三友, 1896

Tong Xing 同兴, 1896

Xu Sanyou 许三友, 1896

Ming Chang 明昌造,1889

Tong Xing 同兴造, 1898

no details of maker, 1874

no details of maker, 1874

no details of maker, 1871

no details of maker, 1880

no details of maker, 1874

Donors: [1] many names, [2] Yee Fung Toy Tong 余风采堂, [3] San Francisco Yong Gao-sheng Troupe 金山大埠永高升班, [4] Huang Ye-ping Tong of Xinhui County 会邑黄冶平堂, [5] Tan Guang-yu Tong 谭光裕堂, [6] Tong-shan Tong 六邑同善堂, [7] Chow Family Association 周爱莲堂, [8] Ji-lan Tong 集兰堂, [9] Kong Huai Tong 孔怀堂, [10] Chicago’s Qi Chang Long 芝城奇昌隆, [11] Ying Chuan Tong 颖川堂.

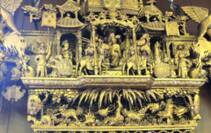

Early Chinese Daoist-Buddhists on this continent were just like Christians in that way. Their semi-private and public “joss houses” were often lavishly furnished. Most had a shrine enclosure made of multiple parts, an altar table with an elaborate facade, and various hanging plaques and statues of deities. Most of these were of wood, carved in relief and covered with gold leaf under many coats of lacquer. The carvings depicted birds, flowers, and episodes from historical dramas.

Occasionally such carvings were done by Chinese artisans based in North America. Those in a few remote places are so amateurishly crude that one suspects a local origin. What is more, in one case we have an actual eyewitness account of carving by an American-based Chinese man. In 1877, a Christian missionary named Warren saw three wood and clay figures of gods being sculpted on the spot for Won Lim Temple 雲林庙 in Weaverville, California; the Chinese sculptor had been brought in from San Francisco especially for that purpose, as reported in an 1877 issue ofThe Home Missionary (New York, vol 49, April 1877: pp 15-16) .

Yet locally made carvings for Chinese temples are rare in North America. The great majority of the carved wood ornaments in early religious structures were imported from China. A number of centers in various parts of that country have long been famous for gold-lacquered temple carvings. However, as far as the editors know, all of the imported temple carvings found in North American shrines came from workshops in only one province, Guangdong. That makes sense. Most early Chinese immigrants to the U.S. came from there.

Early Temple Carvings in Chinese North America

美洲早期华人庙宇木雕

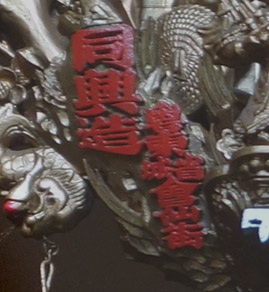

This origin of Chinese temple carvings has not previously been studied in either the United States or Canada. After visiting and recording the contents of the majority of early Daoist and Buddhist shrines that still exist in those countries, we now know where many of their temple carvings were made. It turns out that the older, better-quality carvings, most of them gold-lacquered, often bear the names and addresses of the workshops that made them, along with carved inscriptions giving the names of donors and sponsoring organizations as well as, sometimes, dates in traditional reign-year format. The table below lists 41 examples from shrines and temples in American cities. The dates span several decades, from 1875 to 1911.

Did the sponsoring organizations patronize workshops in their own home towns or carvers of their own language group? Surprisingly, no. Just about all of the examples we have seen come from Guangzhou (Canton), a big city that was not only far from many Chinese immigrants’ home towns but whose inhabitants spoke a language--urban Cantonese-- that was alien to the majority of Chinese immigrants to North America. Yet in spite of this, most immigrants, including Taishanese, Zhongshanese, and Hakkas, seem to have insisted on carvings from Guangzhou and, more specifically, from one of three neighboring workshops – San Xing (三兴), Shi Tai (时泰), and San You (三友) –, close to the north bank of the Pearl River in the midst of a bustling business district. While San You was the oldest and most prestigious workshop, the others also did excellent work. Carvings by San You and Shi Tai still exist on prominent altars in major religious centers within China such as the Chen Ancestral Shrine (陈家祠) in Guangzhou and Foshan's Zumiao Ancestral Temple (佛山祖廟), and in important Chinese temples in Hong Kong and Southeast Asia as well.

As its name indicates, San You was formed by three friends. It started as a single workshop but later divided into three independent units owned by the three original proprietors, who kept the San You name but added their own family names, He (何), Xu (许), and Zhao (赵) as a prefix . Among them, Xu San You was most popular in North America.

Chinese in North America may sometimes have bought such carvings off the shelf, from third-party dealers in China who kept the Guangzhou workshops’ products in inventory. But many customers seem to have wanted the names of their temples, deities, and/or donors to be included on the carved object. Because those names usually appeared in raised relief and under the lacquer and gilding, such objects had to be specially ordered, probably commissioned through one of the Chinese merchants in North America who worked closely with counterparts in Hong Kong and Guangzhou.

Of the 41 examples of temple carving listed below, 24 definitely were made to order. Eleven bear names of donors and seven the names of temples or sponsoring organizations.

List of Workship-signed Carvings from North & South American Shrines 现存北美洲的广州庙宇木雕一览

Shrine, Hongmen Assn, Vancouver, B.C. 温哥华.洪门. "Made by Xu San-you" 许三友, 1906

Shrine, Dart Coon Club, Victoria, BC 维城.域多利.达权. "Xu San-you" 许三友. 1898. (5)

A horizontal hanging plaque, made by Zhao San-you 赵三友造, 1906 (see entry 17 below). Collection and photograph from Idaho State Historical Museum, Boise.爱达荷州历史博物馆

Shrine with multiple frames, Tin How Temple, San Francisco 三藩市天后庙. "Made by Shi Tai" 时泰造 1911 (see entry 14 below).

Boat-shaped hanging plaque, Gee How Oak Tin Assn, Portland, OR

"Made by Shi Tai"

时泰造, 1904?

(see entry 27)

特兰市.

至孝篤親公所

Ref: -Tin How Temple postcard http://foundsf.org/index.php?title=File:TinHowTempleInteriorPostcard.jpg

-Michale Bik, Bik's Picks, Midcentury Merced Revisited.

- Sarah Lim, 2000, "Remembering the Merced Chinese: the Builders of the Great Central Valley 1860-1960." MA dissertation for California State University, Stanislaus, pp.118-120.

Temple Carving Workshops in Guangzhou 广州木雕充实美洲庙宇

Detail of frame for shrine, Lung Kong Tin Yee Assn, San Francisco.

"Made by San Xing" 三兴造 1911. (see entry 11)

The shrines and temples maintained by early Chinese organizations in the U. S. and Canada served not only for worship but as status symbols. As with furnishings in Christian churches built by European immigrants, furnishings of Chinese shrines were partkly meant for show. A costly-looking religious structure demonstrated that the immigrants in question were doing well. The more splendid the furnishings, they must have felt, the more admiration, respect, and even community cohesiveness.

Note 1: Honolulu's Guanyin Temple 观音庙 as an institution was founded in the 19th century, although the building and most of its furnishings are later than 1950. Unusually, it has two bell and drum sets, indicating that some of the temple's furnishings must have come from other temples. One of the drums bears faint characters showing that it belonged to a now-vanished City God temple 城隍庙. One bell is of bronze, presumably of a high-tin "bell metal" alloy; its inscription shows that it was cast in Foshan. We had not known befofe visiting Honolulu that Foshan metal casters ever used bronze for making anything (later note: we now know that they used bronze quite often). The other bell, the one shown here, is of iron and for some reason has had its dedicatory inscription ground away. In view of the hardness of white cast iron, this must have been done with a grinding wheel loaded with a very hard abrasive--probably corundum, carborundum, or diamond. Why the temple or a donor went to so much trouble is not clear: the original owner may have been a temple of another deity, or the original donor(s) may have been unacceptable to the patrons or managers of the present temple. In any case, the bell is likely to be 19th century in date.

Bells as Markers of Trade and Migration 梵钟:贸易-移民网络的一种路标

It turns out that there are a lot of Chinese cast iron bells in the world, many with inscriptions giving dates and names of makers, donors, and the temples/ shrines for which the bells were made (for more information, see the Claudine Salmon reference in Note 2 above). As such they are almost uniquely valuable documents: more durable than wood or paper, important enough in rituals that they are rarely thrown away, and--unlike expensive bronze bells--not intrinsically valuable. The white cast iron of which they are made, being cheap and useless for most other applications, was generally not worth melting down.