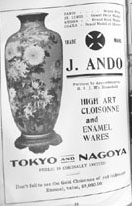

Ando, Suzuki, and Yamaha show products that are still famous after 100 years

安藤 鈴木, 雅马哈日本百年老字号

Ando, Yamaha and Suzuki all exhibited in the AYP Exposition. While the last two would later make products

other than pianos and violins, J Ando & Co. has stayed with its original line. It still makes fine cloisonnes. Luckily we have images not only of its print ads but also its display case in the Japanese building

at the Fair. Click here to view Ando's ad and display case

| ||||

People at Japan Day: The first generation of Japanese-American (Issei) leaders 日本庆祝日行列

One reason why Japan Day is interesting is that articles about it provide us with one of the first substantial Who’s Whos of the Northwestern Japanese community. Although few of the individuals involved had been in the region for fifteen years (Tatsuya Arai, who founded one of the first Japanese-owned restaurants in the U.S., in Tacoma in 1885, and Masajiro Furuya who founded the Furuya Company in 1892, are important exceptions), some had achieved an astonishing level of economic success and cultural integration. This was a generation and a half before World War II, when Japanese-Americans (and Japanese-Canadians) were treated by their governments like hostile aliens and shipped to North American concentration camps.

| ||||

Two or Three Official Philippine Exhibits?

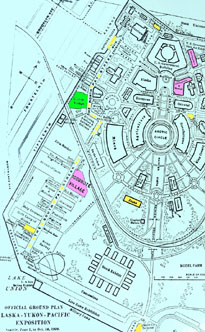

The editors are not clear how many official exhibits at the AYP Exposition featured the Philippines. As shown in magenta color on the map, there were at least two, the Philippines & Hawaii Building and the War Department's Philippines Building, one south and the other east of the pentagonal U.S Government Building. However, some sources say that there was a substantial Philippines exhibit in an alcove within the Government Building. That would make three serious exhibits, along with the non-serious (and much more popular) Igorrote Village.

This image, from a private collection

in Seattle, shows the interior of a

Philippines exhibit at the AYPE. Its

somewhat amateurish look of the

exhibit and the presence of Filipino

commercial products suggests that it

could have been put up by the colonial

government rather than by an East

Coast museum. However, we are not

sure. It could also be part of the

Smithsonian's show.

We suspect rivalry among colonial government agencies. But please check back here in a month or so. The problem should be solved by then.

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

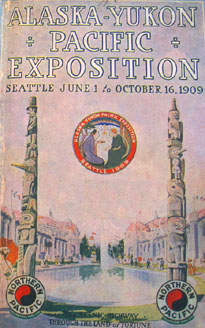

ALASKA-YUKON-PACIFIC EXPOSITION

西雅图1909博览会

This page focuses on the AYPE, held in Seattle in 1909. The purpose of the page is to explore participation by Asian Americans in the AYPE and other fairs. Although such fairs are often denounced as having exploited non-Western colonial peoples, they also offered opportunities to those peoples. In the eyes of resident Asians, they were a potential showcase of ethnic identity, a forum for claiming civil rights, and -- not least important -- a chance to make money.

Title slide

芝加哥西雅图华裔与世界博览会

Chicago's world fairs: an exhibit at the Chinese-American Museum of Chicago

The CAMOC exhibit, 2007

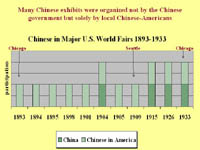

Chinese-Americans vs. Chinese

government in U.S. world fairs

Question: Why did Chinese-Americans get

involved?

Answer: Civil rights, community building, etc. Also making money

Learning non-ghetto skills

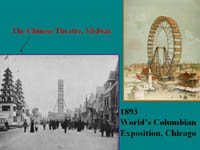

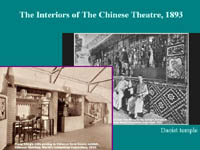

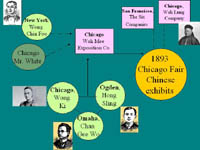

Where it all began: the World's Columbian

Exposition, Chicago, 1893.

Chinese-American exhibits at the WCE

Competing Chinese-American exhibit

organizers for the WCE

梅宗周. 汤信. 陈杰和.等商家

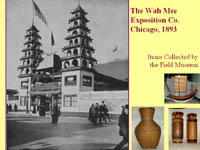

The winner - the Wah Mee Co.'s building

and some of the exhibited objects

Wong Chin Foo used the WCE to press for Chinese civil rights

王清福 民权运动领袖

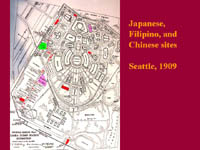

Chinese, Japanese, and Filipino exhibit locations, AYP Exposition 亚裔场地

The Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Expo of 1909

had an Asian (Japanese) themed logo

Japanese exhibits, all government-sponsored

and -funded, outnumbered Chinese exhibits, all

produced by the local Chinese community

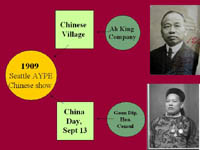

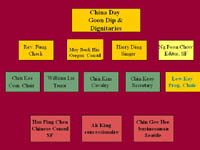

Organizers of the Chinese exhibits at

the AYPE 博览会华裔主力:阿倾, 阮洽

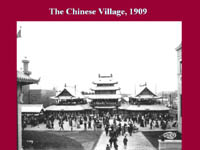

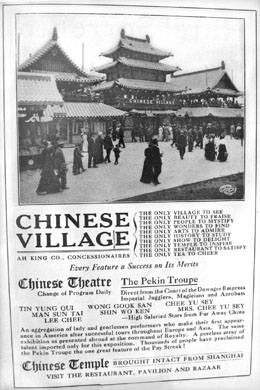

The "Chinese Village" exhibit at the AYP Exposition

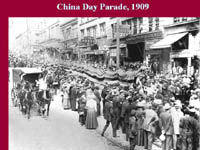

Parade in downtown Seattle for China Day

at the AYPE

One reason for being polite to Japan: The powerful cruisers Soya and Aso, seized in the Russo-Japanese War, were coming to the AYPE on Opening Day, June 1st 1909

Despite anti-Japanese racism, which was

almost as strong as anti-Chinese racism in the Northwest, Japan was treated courteously. See below, Japanese navy

Chinese-Americans and World Fairs

The first fair in which Chinese-Americans played a role was the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago, 1893. It set a pattern that would be followed at other fairs for the next 50 years.

The World's Columbian Exposition of 1893 芝加哥哥伦布纪念博览会

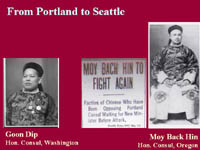

In 1905 Portland Oregon had hosted its own world fair, the Lewis and Clark Exposition. Though overshadowed by St. Louis' great Louisiana Purchase Exposition of the same year, the Portland fair was a success.

Local Oregon Chinese had run the exhibits at the Portland fair. Now some of them hoped to produce exhibits for the Seattle fair as well

The most important of these Portland exhibitors was Goon Dip, who became a Seattle resident.

名誉领事阮洽(左) 梅伯显 (右)

Goon Dip, and Ah King had the biggest

economic stake in the Chinese exhibits

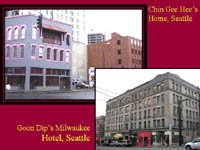

Buildings that once belonged to Goon Dip

and Chin Gee Hee still survive in Seattle

西雅图:陈宜禧故居,阮洽经营的酒店

Local Japanese and Filipino residents were enthusiastic spectators at the AYPE. Some may have been employed there. Did they, like the Chinese, also share in producing and financing exhibits?

[Click on pictures to enlarge]

[Click on pictures to enlarge]

[Click on pictures to enlarge]

As of now (mid-July 2008), research on local Japanese- and Filipino-American participation in the AYP Exposition is still under way. But stay tuned ...

Imperial Jugglers, Magicians, and Acrobats Updated 2/16/09

A Swede from Butte compares China Day and Japan Day Posted 2/15/09

Japan vs. China: Judge Burke takes sides Updated 2/22/09

The genetics of World Fairs: Reverend Fung Chak and Family 冯牧师家族万国博览会结缘 Updated 3/31/09

Seattle's Chinese give President Taft a more modest gift Updated 4/2/09

Igorot attitudes toward the AYP Exposition Posted 2/24/09

Names of Igorots at the AYPE Posted 2/24/09

Igorrote terrifies housewives near Fair Posted 2/26/09

Should Seattle apologize to the Igorots? Posted 7/6/09

More pictures of named Igorots Posted 7/7/09

President Taft accepts a "pretentious" cloisonne vase from Japan 美国总统受大礼 Posted 4/1/09

Rival businessmen unite to build the Streets of Tokio Posted 4/26/09

The Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition, Portland, Oregon,1905

比较波特兰博览会

Most Washington-based visitors to the AYPE, and some of its promoters as well, could only have seen one other world fair - Portland's Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition of 1905. Although the two great Midwestern fairs, Chicago's in 1893 and St Louis's in 1904, provided overall models for the AYP Exposition, the medium-sized and quite successful fair in Portland, held only four years previously, was bound to have a deep influence on Seattle's plans and goals.

One such goal was trade with East and Southeast Asia, already articulated in glowing terms by Portlanders In the words of one spokesman for the Lewis and Clark Exposition,

"Our situation is such that we must be at all times alert and ready. Pacific Ocean commerce undoubtedly has an immense development before it. When the vast populations that border on this greatest of oceans shall have yielded to modern ideas and methods and have been shown how to do what they are capable of ... the result will be the greatest the world has known since the movement that followed the discovery of the Americas."[1]

Interestingly, according to this line of thinking, the East Asian countries could be more than simple markets for American goods. Japan, for instance, at the time in the midst of its successful war with Russia, was "fighting not only her own battle for her national preservation but the battle of other nations, including our own, for the free development of Pacific commerce."[2]

This meant that even in the most virulently racist circles of the Northwest, it was seen as desirable to conciliate the motherlands of despised groups of immigrants. The organizers of both the Portland and Seattle world fairs tried hard to persuade Asian countries to participate and were genuinely pleased by their success. At the Portland fair,

"Participation by Asiatic countries in the Lewis and Clark Exposition has been exceedingly liberal. The Japanese section of the Oriental Exhibits Building contains a very elaborate and instructive exhibit, showing the various products and manufactures for which that country is noted. China made a very thorough and extensive display of handiwork. India's exhibit shows to advantage the marvelous rugs and shawls peculiar to that country. Turkey, Algeria, Persia and Egypt have cast their lots together and made a common exhibit" [3]

Notes

[1] H. W. Scott, "The Momentous Struggle for Mastery of the Pacific" Pacific Monthly 1905, XIV, 1:pp 8-9

[2] same, p 8

[3] Henry Doech, "The Exhibits" Pacific Monthly 1905, XIV, 1: p 30

Landscape with gondola,

Lewis & Clark Exposition

Oriental Exhibits Building,

Lewis and Clark Exposition

These official exhibits, financed by governments and conceived by bureaucrats, had little to do with Asian immigrants. However, they did provide moral support to those immigrants, some of whom were able to capitalize on the prestige of an official Asian presence to create their own displays. The editors of this web site hope to discover more about such displays, situated in the commercial parts of the Fairs -- the "Trail" at Portland and the "Pay Streak" at Seattle -- and frankly money-making in intent. Our thesis is that those displays played important roles in the development of new, assertive Asian-American identities.

Exploiting the Igorots 博览会菲岛土人受委屈

Two parts of the AYP Exposition featured the Philippines: (1) the official exhibits, one housed in a separate building (and built in a very non-Filipino and non-Hawaiian style), and (2) the Igorrote Village, located in a compound of traditional homes and granaries built by members of a tribal people, the Bontoc Igorot, from northern Luzon Island.

The Igorotte Village, with gross ticket sales of $57,471, out-earned every other attraction at the AYP Exposition except the naval battle of the Monitor and Merrimac ($139,596 gross) and the Eskimo Village ($93,402 gross). In comparison, the Chinese and Japanese Villages reported gross earnings of $21,451 and $24,000 respectively. [1]

Groups of Bontoc Igorots (why the fair organizers used the already outdated "Igorotte" spelling is unclear) appeared at several world fairs in the early 1900s and were such a commercial success that impresarios competed to take them on tour elsewhere in the U.S. Even contemporaries found this exploiting of a native ethnic group distasteful, and most modern writers have denounced it as the shameful product of an imperialist attitude, exhibiting subject peoples like zoo animals for the amusement of their colonial masters. An interesting issue has been raised recently, however. Cherubim Quizon of Seton Hall University, although naturally opposed to the idea of showcasing tribal Filipinos as wild headhunting savages, asks whether the experience was all that unpleasant in the eyes of Igorot participants. If it was so bad, she wonders, why did any Igorot agree to participate in later Fairs? Why did some individual Igorots return to the U.S. for a second time? [2]

We will post more about the presence of Igorot at the AYPE and other fairs. It is an interesting story, basically tragic but sometimes quite funny. For more on Igorots and the AYP Exposition, click here or here

Unedited text and many pictures from a 1909 pamphlet about the AYPE Igorot have been posted on the Internet at http://www.aype.net/igorrotesattheaype.html. Some people object to posting anything as culturally insulting as that pamphlet. We think showing it is okay. Modern Americans have to know about the ignorant racism of their ancestors.

[1] http://www.historylink.org/essays/output.cfm?file_id=8635

[2] Unpublished paper given by Quizon at the 2008 meeting of the Pacific Division of the American Association for the Advancement of

Science, Waimea, Hawaii. See also Robert W. Rydell's classic treatment of imperialism and world fairs in All the World's a Fair, University

of Chicago Press, 1984

Big museums compete for AYPE Philippine contracts 博物馆争办菲岛展览

There is some confusion about who was actually responsible for preparing the two or three government-sponsored Philippine exhibits at the AYPE. In official reports, both the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) in New York and the Smithsonian's National Museum (SNM) in Washington claimed credit. It seems likely that each prepared one and that another organization -- perhaps the colonial government i n Manila -- prepared the third.

The two museums were (and are) among the top three natural history museums in the country. Both had fine Philippine collections, although in 1909 less Philippine expertise than the third of the Big Three, Chicago's Field Museum of Natural History. Both had incentives to participate. The SNM needed to keep proving its relevance to skeptical congressmen -- in this case, by showing interest in America's new colonial venture. The AMNH was focused on the $25,000 that had been provided by Congress "to be expended under the Secretary of War to aid the people of the Philippines in providing and maintaining an appropriate and creditable exhibit of the products and resources of the Philippine Islands." [1]

We do not know what the AMNH's exhibit for the War Department looked like. It had

its own building and included ready-made exhibits of cultural objects that had been

acquired at St. Louis" (i.e., at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition of 1904) and first

exhibited in the Philippine Hall of the AMNH before being shipped to Seattle.

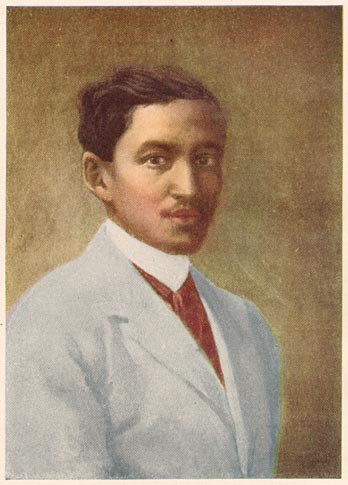

The SNM's 1910 report describes its exhibit in detail. It included painted portraits of

"Eminent Persons Connected with the History of the Philippine Islands" (of whom there

were eight -- six Americans, two Filipinos, and zero Spaniards); exhibits of the arts

and lifeways of several ethnic groups (Negritos, Tagala, Moro, Bagobo, and - yes -

Bontoc Igorot); and many photographs of churches, street scenes, farms, markets,

and so forth. [2] All of these appeared either in an alcove in the main U.S. government

building or in the Hawaii-Philippines Building (see below)

[1] American Museum of Natural History, 41st Annual Report for the Year 1909, (New York,. 1910), p 40

[2] National Museum of Natural History, The Exhibits of the Smithsonian Institution and United States National Museum at the Alaska-Yukon-

Pacific Exposition, 1909 (Washington, DC,1910), pp 13, 51-60

"Family Groups of the Negritos"

U.S. Government Building, AYPE

The Japanese assault Uncle Sam's whiskers 日本节目讨美国人便宜

The following article is reprinted in its entirety from page 14 of the June 28, 1909 issue of the New York Times

SEATTLE, Wash., July 27.-- Following complaints from citizens, who said the game was insulting to loyal

Americans, Director of Concessions G. A, Mattox yesterday closed a booth in the Japanese village at the

Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition, which contained an attraction known as "Assaulting Uncle Sam's Whiskers."

Three plaster busts re[presenting Uncle Sam were in the booth. The "whiskers" were made of strings, which

patrons would pull out, securing prizes according to the numbers attached. The manager of the Japanese

village [one Arai -- eds.], which has no connection with the official Japanese exhibit, said that no insult was

meant and that the game seemed to be popular with the Americans.

CINARC's AYPE page is partially funded by a grant from the 2008 4Culture Heritage Special Projects Program. The same grant has supported a two-day moving symposium in September 2009,on Asian participation in the AYPE

An essential resource for AYPE researchers is the web site of the A-Y-P Exposition Community

(for the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition Centennial, 1909-2009), http://www.aype.org/index.php.

It includes many photographs of the AYPE plus listings for numerous projects connected with the centennial, including the Filipino-American National Historical Society's exhibition Bontoc Exhibit Remembrance and Trish Hackett Nicola's research paper, Chinese Community's Participation in A-Y-P-E. We expect that both projects will complement and improve on CINARC's efforts.

Other important resources are the websites of the AYPE Collectors Group of the Pacific Northwest Post Card Club, maintained by Orville Mallott, and the very active AYPE.COM maintained by Dan Kerlee. The two sites offer large selections of on-line images of the AYPE, plus some excellent original research. Try them and see -- http://www.aype.net and http://www.aype.com

The AYPE's former president remembers Asian VIPs

博览会主席怀念亞裔会员

J. E. Chilberg, the former president of the AYP Exposition, jotted down some  notes about it long afterward. In his own words,

notes about it long afterward. In his own words,

This is the year 1953 and I am the only member of the Executive Committee

still living. As I was active in the business management with knowledge of

all that occurred, I think the record should be made, as it is an integral part of

the history of Seattle ...

Typed versions of the notes were deposited in several places, including the

University of Washington library and the Seattle Public Library. As far as we

know, his comments on Japanese and Chinese participation have not previously

been published. He states that Japan was the only Asian nation to participate officially in the Exposition. It provided its own building[s] and maintained

one of her battleships [presumably the cruiser Aso -- eds.] in Seattle's harbor until the Exposition closed. The

battleship was commanded by Admiral Ijichi, who could speak no English, and I, his host, could speak no

Japanese. My office would receive word by telephone from Consul T. Tanaka, that the Admiral would do

himself the honor of calling on the President at ten o'clock A.M. I would dress in my Prince Albert coat and

striped pants, with my silk hat on the desk, and champagne in the cooler. The Admiral would arrive promptly,

accompanied by his staff. Salutations would be made formally and I would propose a toast to His Imperial

Majesty, the Emperor of Japan. The Admiral would reply by proposing a toast to His Excellency, the President

of the United States. There being no language in which we could converse, we bowed politely and the call

was over ...

Chilberg's relations with the highest ranking Chinese exhibitor, Goon Dip (for more information, click here), seems to have been different. Perhaps he found it easier to relax with Goon Dip, because he, in spite of his rank as honorary Consul, was a fellow businessman and Northwestern resident: Goon Dip also spoke good English.

Goon Dip, Consul for China, raised money and secured exhibits

from his Chinese friends in Seattle, Portland, and San Francisco,

with which he made a very creditable exhibit of Chinese goods. He

provided the great Chinese dragon [about which more later -- eds.]

to precede the procession on Chinese Day, and insisted that

I ride with him in his automobile at the head of the procession.

We became great and good friends until his passing, and to him I am

indebted for most of my knowledge of Confucius and his teachings.

If Chilberg had dealings with other Asians at the AYPE, he does not

mention them.

Igorot "war dance"

performance at the

AYPE, 1909

The Chinese Village makes a profit 中国村盈利

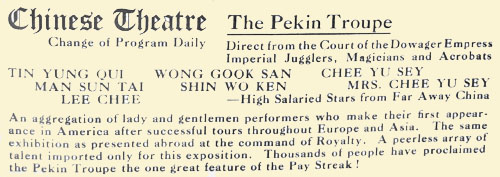

Located in the commercial Pay Streak section of the AYPE and managed by Ah King, a Seattle-based Chinese merchant, the Chinese Village featured a collection of souvenir shops, a restaurant, a Chinese temple, and stage performances by jugglers, acrobats, and magicians. Attractions of these sorts had formed part of Chinese American-run exhibits at all U.S. world fairs since Chicago's 1893 Exposition.

Denounced by some as tacky and praised by others for adhering to high moral standards (i.e., no alcohol and no belly dancers), the Village aimed at making money but billed itself as educational. The Reno (Nevada) Evening Gazette (5/14/1909) was told that the Village would be "another reproduction of the life at home, faithful in every particular. The theatre will be a feature and a section of one of the most famous streets of Pekin will be pictured. The building alone in the Chinese Village cost $14,000." The Ogden (Utah) Standard (3/1/1909) paraphrased a similar press release, :"A street scene of one of the largest cities of China is to be reproduced by Chinese merchants of Seattle to show native life in China as well as to display both historical and educational exhibits."

While the Chinese Village may not quite have lived up to these high-flown promises, it did all right financially. Its declared gross profit of $21,451 (see above, Exploiting the Igorot) must have satisfied Ah King, and the fact that this private venture made almost as much money as the government-supported Japanese Village (see above, ditto) must have pleased many local Chinese.

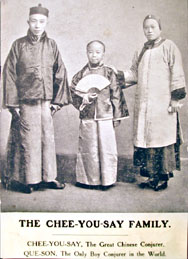

"Chinese magicians long for their son" 上海魔术大师想家

Ever since the spectacular success of the great Ching Ling Foo at the 1898 Trans-Mississippi Exposition in Omaha, magicians from China found a ready welcome from American audiences. The commercial Chinese show at every subsequent U.S. world fair featured them. The AYP Exposition broke new ground, however. Not only did it have several Chinese magicians but two of them were married to each other. The following article appeared in several newspapers while the AYPE was under way.

CHINESE MAGICIANS LONG FOR THEIR SON

Popular Performers Regret Separation from Promising Young Man in Shanghai

Chee You Sey and his wife, magicians of the Tin Yung Qui troupe of performers in the Chinese Theatre at the exposition, present one of the most finished acts in legerdemain ever seen in America and make a very favorable impression by the skill and grace with which they perform their mystifying tricks. While they manifest much enthusiasm in their work and share the delight of their audience, there is at present a shadow in their lives, the nature of which they divulged with considerable feeling during a recent conversation at the Chinese Village.

It appears that the couple have a son 14 years old in Shanghai. The young man has developed into a creditable magician as the result of the long and careful tutelage of his accomplished parents, who are very proud of him. The youthful magician has traveled with his father and mother for several years and it is their separation from him now which gives their stay in Seattle a tinge of regret. However, their engagement here, which is now drawing to a close, has been very successful and they will return to China well satisfied with their first experience in America.

As the above advertisement shows, the Chees were one of several featured acts and did not receive special billing. Even the Chinese organizers of the show may not have realized how unusual it was in America in those days for a magician, and not just a magician's nameless assistant, to be a woman.

Goon Dip with Chilberg in China Day parade, 09/13/1909 中国日博览会主席与阮洽

Imperial Jugglers, Magicians, and Acrobats 杂技艺人与 魔术师

Several of the performers listed in the above advertisement were quite well known

Chee Yu Sey / Chee Yu San [ 朱酉山 - in Mandarin, Zhu Youshan],

(Mrs) Chee Yu Sey / Chee Chung Sey (or See),

Although billed as a troupe from Beijing (spelled "Pekin" in those days), all actually were from Shanghai.

Shows by magicians became popular in Beijing and Tianjin towards the end of the 19th century. The famed Zhu Lianqui, known as Ching Ling Foo in western countries (see the Chinese-American Museum of Chicago's website), was the earliest and most revered of those magicians. Several of the leading troupes, perhaps including the one that came to the AYPE, are said to have performed in the palace for the Empress Dowager.

The leaders of the AYPE troupe were Tin Young Qui and Chee Yu Sey. By the time they reached Seattle, Tin and Chee had been partners for years. They often entertained guests at festival celebrations in Shanghai, including birthday parties for local celebrities.

On September 12 it was announced that the Tin Yung Qui troupe, "having proven an unqualified success, will become a strong attraction on one of the leading vaudeville circuits after the Fair is over. Their tour will cover the principal large cities only, as their stay in the United States is limited under governmental regulations to February, 1910, when they must take their departure for China." [Post-Intelligencer 1909-09-13] The famed magician Ching Ling Foo, joining vaudeville after the 1898 Omaha Exposition, had managed to stay in the U.S. indefinitely. The Immigration Service's attitude toward Chinese magicians seems to have hardened between 1898 and 1909.

One researcher, Trish Nicola, is currently working on Chinese performers at the AYP Exposition. We hope to learn from her what their specialties were and how they adjusted their acts to fit the taste of Western audiences.

Nepotism in the Chinese Village? 博览会中国村伍家天下?

Ah King, who held the concession for the Chinese Village (as well as a "Hot Corn" food stand) at the AYPE, was actually named Ng Hock Moy (the Wing Luke Museum website gives more biographical data). Interestingly, eight of the twelve employees at the Chinese Village had the same family name, pronounced Ng in Cantonese and Wu in Mandarin. Also interesting was the fact that all eight came from Taishan in Guangdong province, the capital of Taishan (= Toisan) district and Ah King’s home town. At least some of these Ngs must have been Ah King's relatives.

Following a precedent set at earlier world fairs, the Immigration Service permitted a certain number of Chinese to enter and stay in the U. S. for the duration of the Seattle exposition. In the past, many of those admitted had tended to disappear when the fair in question was over, before the ever-watchful Service could force them back to China. Most of the performers in Tin's troupe did leave. We doubt, however, that all the Ngs went back.

CantoneseCharactersMandarin Job

Job

People in the China Day Parade 博览会中国日华人行列

The names of a number of participants in the China Day parade on September 13, 1909 have been preserved. Led by Goon Dip and J. E. Chilberg (see above), the parade occurred in two stages, the first between Chinatown and the Pike Place Market area and the second, a few hours later, within the fairgrounds.

Parade Chair:  Goon Dip (honorary vice consul).

Goon Dip (honorary vice consul).

Program Chair:

Lew Kay

Lew Kay

Parade cavalry:

Chin Kim, Lee L.S., Lew Ching.

Chin Kim, Lee L.S., Lew Ching.

Program performers: Chin Kee, Chin Keay, Daniel Goon, Ella Goon, Jim Goon, Harry Ding, Lillian Goon,

Chin Kee, Chin Keay, Daniel Goon, Ella Goon, Jim Goon, Harry Ding, Lillian Goon,

All were Chinese-Americans from Washington or Oregon. Representing the most acculturated part of the local Chinese community, with many years of residence in the U.S. and often American citizenship, many had played or were to play central roles in the history of Chinese in the Pacific Northwest.

Thumbnail biographies of several participants will appear here shortly. So will further details about the dragon and the parade itself.

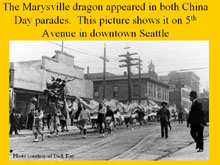

China Day Parade on 5th Ave., Seattle

The Living AYPE Seal 现实模仿艺术 - 美人扮印章

The version on the left is one that was used everywhere as the logo of the AYPE. As pointed out by Orv Mallott

[http://www.aype.net/theofficialseal.html], it was never copyrighted by the artist, Adelaide Hanscom (1875-1932), and hence could be used freely by hundreds of publishers and makers of AYPE souvenirs.

The version on the right appeared in an August 1909 issue of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer. The three allegorical ladies represent the Pacific (holding a toy steamship), Alaska (holding an improbably large gold nugget), and the Northwest (holding a toy locomotive). The PI's version is important not just because of its not-so-uncanny resemblance to the actual seal but because the Japanese lady representing the Pacific, one Miss Koyo, may be the first named female Asian American in this region to appear in a published photograph. The other two ladies, Misses Frances and Fannie Server, both Caucasians, were evidently sisters. It does not seem likely that in reality one sister came from the Northwest (i.e., Washington or a nearby state) and the other from Alaska.

A.Y.P.E. Research, June 2008 西雅图: 阿拉斯加—尤康—太平洋博览会

The following three sections are from a PowerPoint talk given by Chuimei Ho in the summer of 2008, at a meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in Waimea, Hawaii. Chuimei reviews the general subject of Chinese-American participation in world fairs and concludes that this immigrant group often played a more important role in such fairs than did the Chinese imperial and republican governments. In this respect, Chinese-Americans differed from most other immigrant groups. While Japanese-Americans and most European-Americans were content to let the governments of their mother countries explain and define national identities, Chinese-Americans insisted on taking charge. They organized and financed the main Chinese exhibits for a number of fairs, sometimes instead of or in competition with official government exhibits. They did this for reasons of profit, pride, and - perhaps - a feeling that they were better equipped to interpret Chinese culture to Westerners than were their kinsmen and former rulers back home.

Japan Day at the Fair 博览会日本庆祝日 アラスカ・ユーコン 太平洋博覧会

Two separate parades took place. The city parade started in the morning from the Japanese quarter near the present-day International District, marched along First Avenue through Pioneer Square, and dispersed at Yesler and Third Avenue. The marchers reassembled at the Fair grounds just before noon and presented a second parade, followed by lunch, speeches, dinner, and fireworks. The grand prize of the day was a Japanese tea set worth $150.

It is interesting to note that China Day on September 13 repeated the same program, more or less, with two parades, one in the city and one at the fairground, floats, lunches, speeches, fireworks, etc. Clearly, local Chinese had learned from their Japanese counterparts.

AYPE seal, from enameled souvenir item

"Living reproduction" of the seal

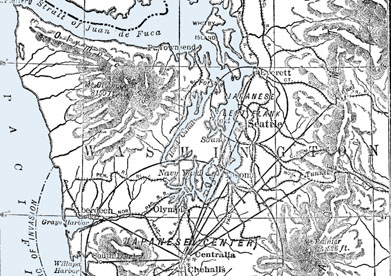

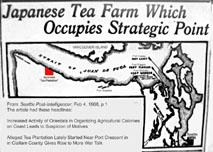

Homer Lea's paranoid vision of a Japanese attack on Seattle, 1909

荷马李的日军侵美战略

The years just before the AYP Exposition had seen a sharp rise in verbal and physical violence against North American Japanese. And yet that violence was kept under tight control by the U.S. and Canadian governments, who were much more vigilant about nativist extremism in 1906-1907 than in 1885-1886, when many Chinese were killed and expelled by the same racist groups that were now agitating to drive all Japanese out. North American governments in the 1900s had not grown more tolerant than twenty years before. They had, however, become more worried about consequences. This was partly because of a book, The Valor of Ignorance, by the eccentric Homer Lea, a military adviser to several Chinese revolutionary leaders. The book was published in the same year as the AYPE. Leaders from both the United States and Japan must have been reading it while the Fair was under way.

The book included imagined plans of attack by Japanese forces on American bases in the Pacific, culminating in the seizure of the main cities of the West Coast of the United States. His plan for the attack on Seattle saw the Japanese navy avoiding the big guns in the forts of Puget Sound and the Columbia River mouth and instead landing troops at undefended Gray's and Willapa Harbors, then advancing eastward to seize the strategic key to the region, the Centralia-Chehalis area.

In later years, the Japanese navy and army were to follow Lea's plans closely in their attack on the Philippines. If they had ever contemplated attacking Seattle and Portland, it is quite possible that they would have followed Lea's advice there as well.

Ardently pro-Chinese and a lover of East Asian culture, Lea was politically opposed to both the Japanese and Russians, whose recent bloody war with each other did not in his eyes nullify the acute danger that both posed to the United States. Hence, he accepted a number of racist beliefs, including the idea that Japanese immigrants were mostly men of military age and that, even if their presence was not part of a master plan for the conquest of America, they would in any case fight on the side of an invading Japanese army. A tragic consequence of this belief was the internment of loyal Japanese Americans in 1942, after the outbreak of the Pacific War that Lea foresaw with almost eerie clarity.

Lea's plan for the Japanese attack on Seattle

Japan's navy, protecting Japanese in America, and the AYPE 日本海军, 驻美日人, 夏威夷入美国版图, 西雅图博览会

The Japanese American community received the visit of the Japanese warships to the AYP Exposition with

wild enthusiasm. Several thousand Japanese residents of Washington and Oregon greeted the Soya and

Aso, hosted their sailors, and filled excursion boats to see the ships at anchor. However, this enthusiasm

had a subtext that is not always appreciated.

Many members of the community were immigrants from Hawaii, where they or their parents had come to work, mainly on sugar plantations, between the late 1860s and early 1890s. They had already demanded the right to vote in local Hawaiian elections in 1887 and had been severely repressed as a consequence. Hawaiian Japanese became especially fearful of violence at the time of the 1893 coup, when an American-controlled provisional government replaced the independent Hawaiian monarchy. They felt threatened again in 1897-98, when America completed its annexation of the islands.

The Japanese government made no bones about its intention to protect its interests and those of its citizens in Hawaii. Twice in 1893 and than again in 1897-8, it sent the armored cruiser Naniwa to Honolulu, where it anchored for an extended period each time it came. This constituted a clear danger in American eyes. When the Naniwa was built in 1884, it had been one of the most powerful warships in the world, and even as late as 1897 it still outgunned and outclassed anything that America had in the Pacific. As pointed out by Assistant Secretary of War Theodore Roosevelt in 1898, the Naniwa was far more powerful than the biggest U.S. ship in Hawaiian waters. The cruiser Philadelphia, then the American flagship in Honolulu, mounted twelve slow-firing six-inch (150 mm) guns. The Naniwa had six rapid-firing six inchers and two rapid-firing ten-inch (260 mm) guns. With a battle-hardened crew (the Naniwa had fought in the naval battles of the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-5), the ship might well have been a match for America's entire Pacific fleet at the time of Hawaii's annexation.

By 1909, the American navy had greatly improved and had no real reason to fear the two somewhat outdated Japanese cruisers that attended the opening of the AYPE. However, the full Japanese fleet was still much stronger (and more combat-experienced) than the U.S. Pacific fleet. Well-informed European-Americans certainly knew this, and so did American Japanese. Memories of the Naniwa must have played a role in the effusive welcome that the Imperial Navy received in Seattle both from white politicians and from Japanese immigrants.

Sources: Wikipedia; Walter LaFeber, The New Empire, 1996: 363-4; New York Times 1898-1-16: 1

Japanese Cruiser Naniwa, 1887

Japanese cruiser Aso, ca. 1910

Japanese cruiser Soya, ca. 1910

Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition Centennial:

Asian Symposium

アラスカ・ユーコン 太平洋博覧会会議

2-day symposium in 2009:

Asian-Pacific Perspectives at the AYPE

Funder: 4Culture King County 2008 Heritage Special Projects

Organizers: Chuimei Ho & Bennet Bronson

Sponsors: the Burke Museum of Natural History & Culture; the National Archives & Records Administration

Only four Asian-Pacific groups participated in the 1909 AYP Exposition: Chinese, Japanese, Filipinos, and Hawaiians. How and why their cultures were presented to fair goers has been a neglected subject. The symposium was intended to reveal stories of Asian Pacific participants as a way of understanding the development of their communities and their images in their own eyes and those of European Americans, some supportive and others fiercely hostile.

First Day symposium:

9/12/2009 (Saturday), at National Archives and Records Administration, Seattle.

Self and Projected Images of Asian and Pacific Immigrants in the Age of AYPE: 1905-1910

亞太裔移民在博览会期间的社会地位与形象 1905-1910

To what extent did the AYPE bring such problems into the open? Filipinos and Hawaiians came as quasi-colonial subjects: was this an advantage or did it cause them to be treated worse by white Northwesterners? Newly arrived Japanese immigrants were bound to be at odds with local Chinese, as the two countries were at war in Asia, and yet they faced similar problems. Did they learn from each other or even cooperate? What role did perceived social class play in European American attitudes toward individual Asians and Hawaiians, in the Northwest and at the AYPE?

How did earlier expositions affect Asian-Pacific participation at the AYP Exposition, and how did the AYPE experience impact Asian-Pacific groups in later years?

Second Day symposium:

9/13/2009 (Sunday), at the Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture, Seattle

Asians and Pacific Participants at the Fair: Fear and Friendship

博览会亞太裔成员: 既惶恐既联谊

Did the theatre, restaurant, temple, and shops at the Chinese Building, managed by one Chinese concessionaire, represent Chinese American or Chinese culture? Why was it important for the Seattle Chinese to bring a large dragon from California for the 9/13/1909 China Day celebration? Did Judge Thomas Burke’s appearance on China Day remind visitors of his healing role in Seattle's anti-Chinese riots in 1886?

What prompted the AYP Exposition committee to adopt Japanese architectural designs at entrance gateways as well as booth stands, in addition to having several Japanese buildings at the fairgrounds? How did the several hundred Japan-based exhibitors interact with Seattle Japanese merchants? How did visiting Japanese aristocrats interact with both groups, not to mention Japanese workers?

Did Chinese and Hawaiians at the AYPE show similar class patterns, and did local whites recognize them? How did Filipino pensionado students at American universities react to the display of “savages” from tribal cultures in the Philippines? Were Northwesterners clear about the distinction between Chinese, Japanese, white, and native Hawaiians?

There was a tour of the fairgrounds (i.e., the UW campus) to examine historical sites used by the Asian-Pacific participants.

For the 2009 Symposium on Asians at the AYPE,

click here

JAPAN AND JAPANESE-AMERICANS

In the Northwest, Japanese outnumbered Chinese by 1909, although racist persecution was

growing despite protection by the Japanese government. That government mounted a major

official exhibit at the AYPE. But local Japanese Americans produced a separate exhibit anyway.

THE PHILIPPINES

Very few Filipinos lived in the region at the time of the AYPE. The exhibits, which included living

Filipinos, were produced by and for European-Americans.

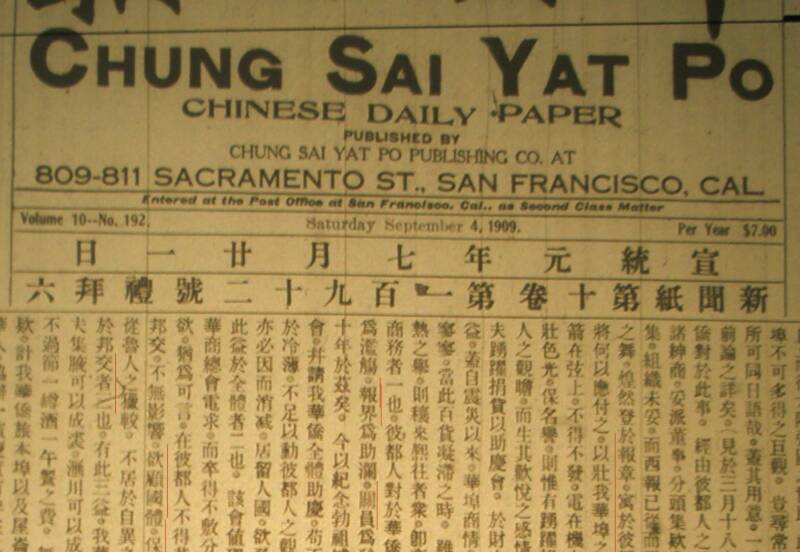

Pacific Coast Chinese American newspaper on AYPE 中西日报对赛会的报道

A California Chinese newspaper on why local Chinese should take part in expositions

The AYP Exposition was unusually quiet among the Chinese-language newspapers on the West coast. The San Francisco-based Chung Sai Yat Po, the most popular newspaper in the region, mentioned the event casually and paid much less attention to Chinese involvement in the AYPE than did English-language papers in Seattle.

"Financial sponsorship will no doubt drain our resources but will be beneficial to community members. Since the 1906 Great Fire business in Chinatown (in San Francisco) has not been good and tourists to Chinatown have been few, in spite of many stimulating campaigns. A major festival could be an effective way of revitalizing Chinatown. This is the first good reason why we must participate.

"People here have developed hard feelings toward Chinese-Americans, based on ethnic differences. For the past twenty to thirty years, trade unions have provoked this negative feeling. Newspapers have promoted it, the Immigration Bureau endorsed it, and government officials refused to act on it. Now because of the Portola Fair they have invited our whole community to participate. If the community declines, or does not throw itself into it whole-heartedly, then the little good feeling this country’s people have about us will surely be diminished. Residing in this country we must learn to follow the local traditions to avoid being abused or humiliated. This is the second good reason why we must participate.

"The Portola Fair Committee invited China to send a warship to San Francisco as part of the celebration and the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association repeated that request but China turned both these appeals down. It was all right for American Chinese to be rejected but not for other Americans. They will feel discouraged and this will affect Sino-American relationships. In order to uphold national dignity, to strengthen relationships between our countries, and to avoid being seen as different, we must go with the flow and not to stand aloof. This is the third good reason why we must participate.

"With such three good reasons, we Chinese-Americans must jump onto the wagon. We understand that a fur coat is made of many pelts and that the sea gathers from many streams. If we can only put aside the cost of a bottle of wine or a lunch, which would not hurt in any way, that would fill a large pot of money. With just a dollar contribution from each of the 10,000 Chinese in San Francisco and Oakland, we could assemble an impressive level of funding for an impressive celebration.

"We Chinese-Americans have had the reputation of good at sponsoring festive events. Most celebrations are confined to one city or state. But this one will have international participation and will be watched by many people all over the world. We American Chinese cannot let this chance go and be laughed at for having missed it.”

CHINA AND CHINESE-AMERICANS

The Chinese population of the Pacific Northwest had fallen sharply since the anti-Chinese riots

of the mid-1880s. China, unable to protect local Chinese, did not take part in the AYPE. And

yet those local Chinese, with surprising confidence, chose to mount a China exhibit of their own.

The editor of the Chung Sai Yat Po, Ng Poon Chew, came from the same home town as Ah King, the Chinese Village concessionaire at the AYPE. He had the same family name, Ng, as Ah King. He must have known Ah King quite well, and his newspaper circulated in Oregon and Washington as well as California. And yet Ng virtually ignored the Seattle event. Perhaps he felt that the AYPE was less newsworthy than the much smaller but closer Portola Fair in San Francisco, which opened on October 19, 1909. He covered that one in far greater detail. In an editorial dated September 4, 1909, Ng listed several reasons why the San Francisco Chinese community should sponsor Chinese celebrations at the Portola Fair. We translate Ng’s very persuasive editorial here. Similar arguments must have been presented to the Seattle Chinese community for it to have agreed to take over the job of representing China at the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition.

“The purposes [of the Portola Fair] are one, to love the state, and two, to stimulate the state’s business … Our Chinese community has been invited to participate and the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association has become involved in fund-raising. But now, before the funding is completed and plans finalized, English newspapers have already begun beating the drums for us – rumors of a 300-feet dragon and a 600-person dragon dance have been reported to many mainstream readers. How are we going to respond to these challenges that would brighten Chinatown without hurting our reputation? We are being put on the spot and must react, just as an arrow that is drawn on a bowstring must be released. Our only option now is to sponsor the event enthusiastically, so that our colors will brighten the vision of this country’s people and our efforts will please their minds.

Ng Poon Chew, 1913

伍盘照

THE A-Y-P EXPOSITION AND OTHER FAIRS

The AYPE was not the first world fair for Asians living in the U.S. They had joined such fairs

since 1893. The fairs played a central role in the growth of new Asian-American identities

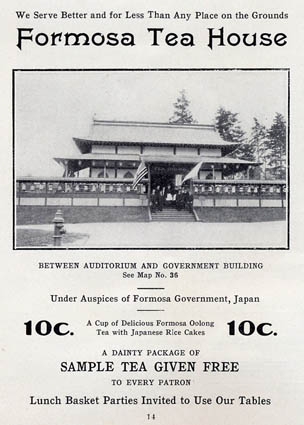

The Unexpected Fate of the Formosa Tea House 赛会后台湾茶馆去向

In the early 20th century, Japan used world fairs to show off its newly acquired Asian colonies. It put major efforts into fancy exhibits on Formosa (now Taiwan), seized from China in 1895, at expositions in St. Louis (1904), Seattle (1909), London (1910), San Diego (1915), and San Francisco (1915). An equally fancy exhibit materialized at Chicago's Century of Progress Exposition (1934-5), featuring Japan's new puppet kingdom, Manchukuo, created from Chinese Manchuria in 1933. None of these Japanese colonial exhibits was pleasing to Chinese-Americans, who had their own exhibits at those fair and who naturally did not sympathize with Japan's pride at converting parts of China into colonies.

As far as we know, Japanese-American girls were not allowed to join the YWCA in the Seattle area in the 1910s and 1920s. Anti-Japanese prejudice was strong. We doubt that Chinese- and Filipino-American girls were welcomed either.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Panama-California_Exposition_(1915)

ASIAN-PACIFIC WOMEN AND THE AYPE

Women's suffrage was a big theme at the Fair, and Washington women won the right to vote in the next

year, 1910. However, as shown by images of Asian-Pacific women at the Fair, sexism was hardly dead

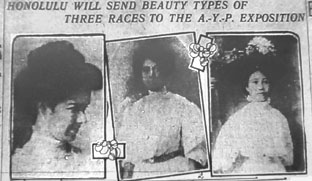

"Beauty Types of Three Races" 代表夏威夷三位美人

Like most American fairs since the World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893, the AYP Exposition gave time and space to feminist causes. Not only did the AYPE feature a special Women’s Building, which still survives as the University of Washington’s Cunningham Hall, but it included a Woman Suffrage Day on July 7th and a National Council of Women Day on July 14th, both timed to coincide with the 41st Annual Convention of the National American Woman Suffrage Association which was held in Seattle that year.

Other women-centered celebrations at the AYPE were more limited in scope, like Daughters of the American Revolution Day and Women’s Christian Temperance Union Flower Mission Day. And still others were of a kind that feminists cannot have approved of, such as a contest for Pay Streak Queen and a Ballet of Beauties, although these, naturally enough and in spite of the puritanical attitudes of the AYPE's organizers, were enormously popular with less high-minded fairgoers.

Many local Asians (who were mostly Chinese and Japanese) must also have disapproved of beauty contests. After all, they came from cultures that prized feminine modesty, not to mention premarital chastity, and yet here they were in an environment where the white population would react negatively to more-modest-than-thou attitudes and where real social benefits could come from showing that one’s younger womenfolk could be simultaneously as respectable and good-looking as the American debutantes whose portraits filled the newspapers of every major city.

Asians did of course distinguish between female entertainers and decent young ladies and would have had no objection to the former parading around in saucy Paris fashions while chatting with strange men of all nationalities. This must have been the attitude of resident Japanese toward the appearance in Seattle of the “ten tiny maidens” who “helped while away the hours” for American naval officers during the Great White Fleet’s visit to Tokyo in 1908. In spite of the Post-Intelligencer’s claim that these maidens, 16-22 years old, were “daughters of the most aristocratic families of ancient Nippon,” it seems likely that they were professionals and, as such, uncontroversial in the eyes of local Japanese.

But what are we to make of the inclusion of a seemingly respectable Japanese girl, Miss Koyo, in the widely published photograph of a living AYP Exposition seal, as shown near the top of this web page? Or what of this photograph of “Beauty Types of Three Races,” from a May 24 1909 issue of the Post-Intelligencer? It shows a white girl named Sophie De La Nux, a Honolulu bookkeeper whose father was connected to French nobility; a native Hawaiian girl, Elizabeth Victor, from Hilo on the Big Island; and a Chinese girl, Florence Ho, who was the first girl of her nationality to graduate from the prestigious Punahou School of Honolulu, now famous as the alma mater of Barack Obama. Was Florence Ho’s family not horrified? How can they have reconciled traditional Asian family values with her appearing as a “beauty” in a Seattle newspaper?

It seems to us that American-based Chinese and Japanese, not to mention Filipinos, abandoned those values with surprising ease. Some must even have liked the idea of their daughters participating in such events. Soon after the close of the AYPE, Asian Americans were already organizing their own beauty contests – the first Miss Chinatown contest was held at San Francisco’s Panama-Pacific Exposition in 1915. The question is, why? How did it happen that immigrants from tradition-bound rural societies could have caved in so completely on an issue that one would think lay close to the core of their perceptions of cultural identity?

The editors propose to discuss this question at greater length in the future. In the meantime, comments from readers will be gratefully accepted. [This "Beauty Types" feature was reprinted in the February 2009 issue of Northwest Hawai'i Times]

The AYPE Women's Building as it appears today

Left to Right: Caucasian, Polynesian, Chinese

The AYPE and the 1906 Chinese Commissioners Visit 出洋大臣与赛会人选

That a few hundred Seattle Chinese decided to go it alone and create their own exhibit after the Chinese government declined to take part posed a major organizational challenge. Putting together a Chinese Village plus elaborate China Day celebrations needed both confidence and ability. Luckily, the community already had practice in such things. Its organizational skills and financial strength had been tested three years earlier during the visit of Prince Tsai Tseh 戴泽 and the two other Imperial commissioners. Several of the main players in those events were also important participants in the AYP Exposition. Other 1906 players, however, did not take part in the AYPE’s parades, exhibits, and banquets, and certain of those who were central to the AYPE celebrations had not attended the reception for the Prince. It is clear that a major shakeup in Seattle Chinese society was taking place. New leadership was emerging, and ties between Portland and Seattle were becoming stronger.

Ah King ( 阿倾) had been present at the prince’s reception under his regular Chinese name, Ng Hok Moy. His Ah King Company (a.k.a. Ken Chung Lung Co.乾昌隆) seems not to have been prestigious enough to be included as a sponsor; only five well-established Chinese businesses were on the list. Ah King was relatively new to Seattle in 1906. Eleven years earlier he had registered himself as a merchant in Spokane, associated with Yee Yuan Company in that city. However, he seems to have done well in Seattle. By 1909 he had enough money and connections to bid successfully to be the sole Chinese concessionaire at the AYPE, a role that made him a major community leader.

Goon Dip, originally a Portland merchant, was already doing business in Seattle in 1906. He was already rich. In 1909 he was to become Honorary Chinese Consul for Washington, Idaho, and Alaska, a title he retained until his death in 1933. He maintained a low key at the Prince’s reception. Why? Perhaps because – as suggested elsewhere on this website – he was not yet popular among Seattle Chinese at that time. In later years any unpopularity would have been lessened by his generosity and efficiency in organizing China Day at the AYPE. The same was true of a strategic marriage in 1911 between his pretty daughter and a groom from an established Seattle Chinese family. That new son-in-law was Lew Kay, the promising young man who gave a welcoming speech to Prince Tsai in 1906 and who served as the program chair for China Day in 1909.

Lew Kay's father, Lew King, died before the AYPE began. However, Chin Gee Hee was still absent from the festivities, preoccupied with building a railroad in China although his Quong Tuck Company continued to loom large in the Northwestern Chinese economy. And Chin Chow Too, ex-president of the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association, did not play a role in the AYPE events either.

Lew Kay, China Day program chair, finds romance at the Fair 刘吉祺赛会结良缘

When the Fair began, Lew Kay had just graduated from the University of Washington: the first Chinese to do so. The local Chinese community had already shown its pride in him during Prince Tsai Tseh's visit three years previously, so it made sense that he would receive a leading role in the China Day celebrations, to give a keynote speech and to serve as program chairman. He may have been chosen for another reason as well. He was a handsome and highly eligible bachelor. The chief China Day organizer, Goon Dip, had a pretty and equally eligible daughter, Rosaline. At 17 and well-educated as well as rich, she would be a perfect match for the new 21 year-old college graduate.

There is no evidence that Goon Dip and Lew King, Lew Kay's father, had arranged the marriage in advance, although that is the way traditional Chinese marriages happened in those days. As far as we know it was more or less a love match and the young couple took their time about marrying. Although they met for the first time in connection with the AYP Exposition, in late 1908 or 1909, they did not marry until 1911, when Lew Kay came back from a stay in China to marry Rosaline. Their splendid wedding ceremony will be described elsewhere on this web site. For the moment it is enough to say that the wedding was not only lavish and American in style but favorably reported by the Portland and Seattle newspapers. As the AYPE had shown, Chinese (and Japanese) were learning American cultural codes and finding these to be an important key to lessening ethnic prejudice.

Part of the China Day parade in front of the AYPE's

Chinese Village. The men in the car wear Chinese

court costumes. The 2-man dance lion on the left

is the only evidence that lion dancers appeared at

the Fair. Lew Kay, wearing a flat cap and a bowtie,

is on the far right.

Another part of the parade passes unidentified AYPE buildings. Rosaline Goon, behind the driver and in front of a veiled woman who might be her mother, wears Chinese dress. The identity of the Chinese man seated to Rosaline's left is not known.

This image did not appear with the newspaper article. The editors recently found it in a photograph album belonging to an old Seattle Chinese family. Probably taken in China, it may be the only surviving picture of all three magicians. The boy (who did not come to the AYPE) was named Queson.

| ||||

The Smithsonian's Philippine Exhibit at the AYPE

Asian Exhibits at the AYPE

Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition Centennial:

Asian Symposium

September 12-13, 2009:

Asian-Pacific Perspectives at the AYPE

Program

There were eight sessions in two days, with each session followed by a 15-minute commentary and discussion. Most of the presentations were 30 minutes long. For detailed resumés of speakers & commentators, Click here.

9/12 (Saturday, NARA, Seattle Branch)

Self and Projected Images of Asian and Pacific Immigrants in the Age of AYPE: 1905-1910

9:00-16:30 All-day exhibits of (1) Photographs from NARA's Files (curated by Susan Karren, NARA ) and

09:25 Welcome: Candace LeinHayes, National Archives and Research Administration (NARA)

09:28 Introduction: Bennet Bronson. CINARC

Session I. Chair: Lorraine McConaghy. Historian, Museum of History and Industry, Seattle.

09:35 Chuimei Ho. CINARC and Founding President, Chinese American Museum of Chicago

10:05 Jeffer Daykin, Portland State University & Portland Community College.

Session II. Chair: Priscilla Wegars. Curator, Asian American Comparative Collection, University of Idaho.

11:10 Sarah Nelson Smith. formerly Archivist, National Archives and Records Administration, Seattle.

11:40 Trish Hackett Nicola. Independent Researcher, Seattle.

13:15 Short tour of NARA's research facilities, by Candace LeinHayes

Session III. Chair: Gail Nomura. Associate Professor, American Ethnic Studies, University of Washington

13:38 Dorothy L. and Fred Cordova, Executive Director and Founders, Filipino-American National Historical

Society & Adjunct Professors, University of Washington

14:08 Ken Tadashi Oshima. Associate Professor, Department of Architecture, University of Washington.

Session IV. Chair: Connie Sugahara. Board Member, Cherry Festival Committee, Seattle.

15:10 David A. Rash. Roof Consultant/Intern Architect, Madsen, Kneppers & Associates, Inc. Seattle.

15:40 Dan Kerlee. Historic Image Specialist, Seattle

Concluding Remarks: Marie Rose Wong. Associate Professor, Urban Planning, Seattle University

9/13 (Sunday, the Burke Museum)

Asian and Pacific Participants at the Fair: Fear and Friendship

9:30-5:00 All-day viewing of exhibtion: Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition: Indigenous Voices Reply

9:30 Welcome: Carl Sander, Education Department, Burke Museum

9:33 Introduction: Chuimei Ho, CINARC

Session V. Chair: Bettie Luke. Executive Director, Organization of Chinese Americans, Seattle.

09:37 Richard Kay. Retired Pharmacist, Seattle, with Bennet Bronson, CINARC

09:52 Howard King. Retired Engineer, Seattle.

10:07 Tina Song. Independent Architect, Seattle.

Session VI. Chair: Assunta Ng. Publisher, Northwest Asian Weekly, Seattle.

11:09 Martha Hoverson. Librarian, Hawaii State Library, Honolulu.

11:39 Shea Shizuko Aoki, former Board of Directors, Japanese-American Citizens' League, Seattle, with

11:54 Michele Whitman. Independent Researcher, Bainbridge Island.

13:15 Fairground Tour (led by Friends of Seattle's Olmstead Parks)

Session VII. Chair: Connie So. Senior Lecturer, American Ethnic Studies, University of Washington.

14:32 Cherubim Quizon. Associate Professor, Anthropology Department, Seton Hall University.

15:02 Patricia Afable. Anthropologist, Department of Anthropology, Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C.

Session VIII. Chair: Robert W. Rydell. Professor, Department of History, Montana State University.

16:07 Bennet Bronson. CINARC and Emeritus Curator, The Field Museum, Chicago.

Concluding Remarks: Robert W. Rydell.

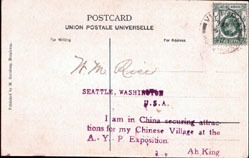

Ah King sends a post card back to Seattle from China 阿倾从香港寄出的明信片

Dan Kerlee, webmaster of www.aype.com, has made an important discovery: a postcard sent by Ah King from Hong Kong to Seattle in connection with the AYP Exposition. It may be the only such document in existence. Post-marked "9 Jan 1909," it shows that Ah King kept close touch with Washington State contacts while on his buying trip to Hong Kong and China, known from other sources to have lasted from December 2008 to June 2009. He got back at just about the time that the Exposition and his Chinese Village opened.

That he dared to absent himself from Seattle at such a critical time proves his trust in his assistants. They must have had to resolve on their own most of the problems that arose in building, stocking, and manning the Village, which would have represented much of Ah King's money. Why he was willing to take such a risk is unclear. Perhaps, as suggested above, he felt that bringing some of his kinsmen over to America had as high a priority as safeguarding his investment in the Village.

Although a talented businessman and presumably a good talker in both Cantonese and English, Ah King was illiterate in the latter language. Hence it made sense for him to use rubber stamps. We do not know who W. M. Rice was. The 1909 edition of the U. S. Civil Services Commission's Official Register of the United States lists one W. M. Rice as a Special Agent of the Treasury Department in Seattle. Ah King may have been addressing him. However, we do not understand how a card with such a skimpy address could have reached him. Was Rice famous enough for Post Office clerks to have recognized his name and forwarded the card to the proper street and building? Or was this the kind of service that one got from the Post Office in those days?

Front. The Victoria Peak Tram is still a major tourist attraction in Hong Kong. (Photo courtesy of D. Kerlee)

Back. Ah King used two rubber stamps. The postage stamp shows King Edward VII

(Photo courtesy of D. Kerlee)

A Swede from Butte Comments on Japan Day and China Day

Spectators disagreed about which exhibits and special days they liked best. One such spectator, from the gold- and copper-mining town of Butte, Montana, gave the following report upon his return home. It should be noted that he may not have been a neutral judge. While he probably knew something about the customs of the Chinese, of whom there were many in Butte in those days, he cannot have had much previous contact with Japanese or Japanese culture.

Charles Bergman, one of the well-known Swedish residents of Butte, is back from the big fair at Seattle and he enjoyed every minute of his two weeks’ vacation.

“I was there during two important days,” he told a Standard reporter yesterday, “Japan Day and China Day. The China day was the best by far. The Japanese appeared to think that their appearance in parade was enough to awe all spectators, and there were no interesting features.

With the Chinese it was different. They went much on display, and where so many came from I could not imagine. They were in line by the thousand, and such elegant costumes worn by the rich Chinese merchants and their wives I never expect to see again. Then there were the floats and designs and banners. Every device in the parade had its especial significance, and it told a story to those who understood Chinese lore. The thing which struck me most favorably was a monster dragon. It was all gilt and tinsel and it was most imposing, being a full city block in length, and it twisted and squirmed its way along the street in a most realistic manner … it surely was so realistic that it almost frightened many of the women spectators.” Anaconda Standard, 09-20-1909, p 6

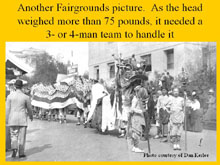

Dragon in parade on China Day, within fairgrounds

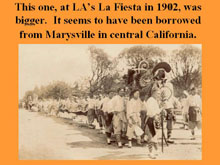

Lost Dragon Found 龙头再现 - 西雅图1909 年赛会龙舞悠悠百年

The great parade dragon that formed the center of attention on China Day was borrowed, not locally owned. Chinese communities in America were closely connected and could usually be counted on to help other communities. In the case of the dragon, it was the rich gold-rush town of Marysville in California that agreed to lend Seattle one of the largest and finest dragons in America, 150 feet in length and needing sixty strong men to carry it. According to the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, it was brought from Marysville in sections,"at great expense," and assembled in the afternoon before the China Day parades [1]. As the preceding article from the Anaconda Standard notes, the dragon was a smash success with Seattlites.

Now that same parade dragon, a hundred years later, has been found. On a recent visit to the Bok Kai temple in Marysville, the editors photographed a splendid, well-preserved but no longer usable, dragon head. Comparing it with photos of the AYP Exposition dragon leaves no doubt. They are identical.

The find is an exciting one. Marysville's dragon is the largest and most important Asian artifact to have survived from the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition.

Ref: [1] Post-Intelligencer 1909-09-13: p 1

The AYPE dragon in 1909: closeup from the photo in the preceding article

Dragon head in the Bok Kai temple,

Marysville, California, 2008

Japan vs. China: Judge Burke Takes Sides

Judge Thomas Burke had (and has) a place in the hearts of all Seattle Chinese, for it was he who, with extraordinary courage, faced down a dangerous mob during the anti-Chinese riots of 1885, saving the lives of many local Chinese-Americans. It must have come as a shock, then, for Chinese to hear about the speech he gave to a Japanese-American audience on July 21 1909 at the official opening of the Japanese government exhibit of the AYPE:

What happened to Japan at the close of her victorious war against China? Nearly the whole world believed that China by the mere brute force of her overwhelming numbers would crush Japan, When, however, by steady and persevering courage, great efforts and great sacrifices Japan came off victorious, one of the most powerful nations of Europe with the tacit consent of the rest, stepped in and, taking advantage of Japan's weakness and exhaustion at the close of a great war, compelled her to give up the fruits of her well earned victory.

Burke was referring to the Sino-Japanese war of 1895, which resulted in

a decisive Japanese military success and then in intervention by Russia

("one of the most powerful nations of Europe"). That intervention forced

Japan to give up part of the territory it had won ("the fruits of her well-

earned victory") -- i.e., northeastern China. Seattle Chinese cannot have

been pleased to hear that one of their heroes thought that a major part of

their native country should belong to Japan.

It is not hard to see where Burke was coming from. Many Americans

at that time admired Japan for its progressive spirit and its military prowess,

as shown recently in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-5. Burke was clearly

one of those admirers. He also had economic reasons to favor Japan, which

was not only an important trading partner of his city but a highly profitable

customer of the railroad Burke represented, the Great Northern.

Seen in this light, Burke's pro-Japanese attitude is not a surprise. He did not in fact turn against Chinese-Americans. He attended Chinese events and hosted Chinese dignitaries at the Fair. He continued to give speeches about the importance of China to Seattle's future until his death in 1925. However, he had his personal preferences, and those were evidently for Japan over China.

Source: University of Washington Library Special Collections, Thomas Burke Papers, Folder 32-5

Judge Thomas Burke

Igorot Attitudes toward the APYE

Changes have occurred in the way we look at Bontoc Igorot involvement in early 20th century world fairs. Until recently most of us regarded it as an unalloyed tragedy – a vile exploitation of a helpless tribal people by colonialists who not only made money from exhibiting them but used their supposed primitive state to argue that the U.S. was justified in keeping the Philippines as a colony. Our opinions were strengthened by books like Robert Rydell’s scathingly anti-imperialist All the World’s a Fair (1984) and films like Marlon Fuentes’ moving documentary Bontoc Eulogy (1997).

Now, however, although we still must condemn the idea of exhibiting Filipinos like zoo animals (a point made by José Rizal, the father of Philippine independence, as early as 1886), we are forced also to consider the point of view of those particular Filipinos. Why? Because a handful of pioneering Filipino anthropologists have begun to talk to the descendants of the Igorots who came to the world fairs. As pointed out by Drs. Patricia Afable and Cherubim Quizon, those descendants do not see the fairs in terms of degradation and shame. They feel that their grandparents benefited from their trips to America. They made money and saw the world. They became expert showmen. Many returned to the U.S. several times in the years between the St. Louis Exposition of 1904 and the Philippine government’s ban on Igorot shows in 1914. Children and grandchildren were proud to be descended from"Nikimalika,” those who went to America.

At least 200 went, according to Afable, and took part in numerous state, city, and county fairs as well as several major international expositions.

Rizal, José Letter to Blumentritt, November 22, 1886

Afable, P. 2000 Igorots in Exposition, The Igorot Quarterly Oct-Dec, pp 18-30;

Afable, P. 2004 Journey from Bontoc to the Western Fairs, 1904-1915, Philippine

Studies, vol 52, 4: pp 445-473

Names of Igorots at the AYPE

Afable (see above) has pieced together a list of more than110 names of Igorotwho were in St. Louis (1904), Portland (1905), Chicago (1907), and other U.S. cities. The names of most of the Igorots in Seattle in 1909 had been recorded by Seidenadel in Chicago in 1907.

We are pleased to be able to offer the names and pictures of four Igorots who definitely were at the AYP Exposition. They come from the expanded "Igorrotes" page of Orv Mallott’s postcard-oriented website, www.aype.net. As far as we know, these particular cards have not previously been noticed by historians. Mallott deserves congratulations for his discoveries.

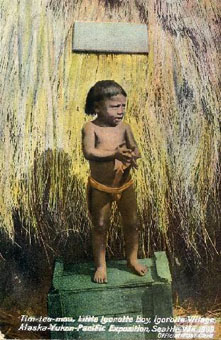

Antero Cabrera, who spoke good English, recruited many of the other 40 Igorot participants. All had been in the U.S, since 1907. He and his wife, Esting, Isding, Takhay, or Cristina, had been married for at least two years. The infant may be Sylvia, named for Pennsylvania, the state where she was born. Agonay or Akunay is identified here for the first time as the mother of a 6 month-old baby known to been part of the group. The boy Tim-Tee-Mou seems not to appear on any of Afable's Igorot name lists.

Antero Cabrera

Tim-Tee-Mou

(The AYPE's attitude toward Igorots was less positive than the Igorots' attitude toward the AYPE. The following article is reprinted in its entirety from the August 6 1909 issue of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer)

Igorrote Terrifies Housewives Near Fair

Head Hunter Escapes in Woods and Police are Quickly Summoned

An unclad and more or less untamed headhunter from the Igorrote village on the Pay Streak took to the woods south of the exposition grounds yesterday morning, and when he did, according to complaints filed with the police, most of the inhabitants in the immediate vicinity took to the taller trees. Two mounted patrolmen of the city force and a pair of guards from the exposition department spent the better part of the afternoon trailing him from one secluded house site to another, and finally rounded him up and took him back to the village without a struggle.

The Igorrote was given permission by the village management to go into the brush to cut handles for the spears which the headhunters sell on the Pay Streak. He neglected to take luncheon with him, and when the noon hour came along, and with it his appetite, he approached the first house he saw and smilingly asked for food.

Somehow or other the woman of the house could not reconcile that bland Igorrote’s smile with the head ax and “gee string,” and she left the savage grinning at the front door while she went out the back on a hot foot for the nearest telephone. From then on both the exposition guards and the city police were deluged with cries for help from frightened householders, and it was not until late in the afternoon that the hungry warrior was rounded up and run back on the reservation.

Once in the village he was locked up in the village “booby hatch,” sentenced to bread and water, and denied the privilege of selling either spears or rattan rings for a week.

The story did not end in tragedy. He was not shot dead by a nervous citizen or policeman. But the story is heart-wrenching nonetheless. Who could not feel pain at the thought of an ordinary hill farmer from the northern Philippines, who had already been in the U.S. for two years and had undoubtedly seen more of America than most of the terrified housewives, "escaping" and being rounded up like a dangerous animal?

[Dan Kerlee (www.aype.com) has just pointed out to us that more AYPE postcards with names of Igorots exist. We have now added Dan's cards to this website. To see them, click here]

Partial Solution (3/6/2009). There were only two. The map is incorrect. The building designated "Philippines and Hawaii" was for Hawaii only, while the main government building housed the Smithsonian's exhibits of Philippines, Guam-Samoa, U.S. archaeology & history, etc., material. Our source is an authoritative-seeming article in The Coast, July 1909: pp 26-9. The above photo is pretty clearly the exhibit of the Smithsonian, not that of the War Department/American Museum of Natural History.

Northern Pacific Railroad guidebook for the AYPE.

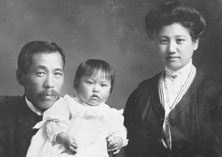

At the time of the AYPE Masajiro Furuya (1863-1938) was the richest and most influential Japanese in the Pacific Northwest. We believe this to be the best photo of Furuya yet to be published. The property of a senior Seattle Nisei, it depicts him with his wife Hatsu and his daughter. A poorer image from the same negative appears in Kazuo Ito, The Issei, Seattle 1973: p 700. See also the Furuya House entry elsewhere on this website. 古屋政次郎

José Rizal was in Europe in 1887, when Spain still ruled the Philippines and a group of Igorots was brought to Madrid for the Exposición de las Islas Filipinas, held in the city's Zoological Garden. Contemporary Spanish reacted in the same way as many Seattlites two decades later, with fascinated contempt. Rizal was outraged. His fiery protest echoes in our ears today.

"I have worked hard against this degradation of my fellow Filipinos that they should not be exhibited among the animals and plants! But I was helpless. One woman has just died of pneumonia ... and the newspaper El Resumen has made a smutty wisecrack about it! And La Correspondencia de España even says 'The Filipino colony in Madrid is enjoying the most perfect health; up to the present, no more than two or three have fallen ill of colds and bronchitis.' I need hardly comment on this.

"I would rather that they all got sick and died so they would suffer no more. Let the Philippines forget that her sons have been treated like this -- to be exhibited and ridiculed."

The Father of Philippine independence and Madrid's 1887 Igorot Exhibition

This was the first of all Igorot shows. Ironically, it was condemned by the greatest of all Filipinos. Yet Rizal's eloquence had no more effect than the many American voices (including Teddy Roosevelt's) that protested Igorot shows over here. There was money to be made and a prejudiced public to be pandered to. The Philippine colonial government did not succeed in banning Igorot shows until 1914, just in time to derail American entrepreneurs' plans for a major Igorot village at San Francisco's 1915 Panama Pacific Exposition.

The Rizal quote is from William Henry Scott's History on the Cordillera (Baguio, 1975, p 13).; data on the end of Igorot shows are from

Patricia Afable, Journeys from Bontoc 1904-1915 in Philippine Studies, 2004, pp 445-474; the image of Rizal is from Wikipedia Commons

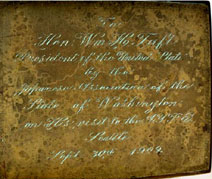

Seattle's Japanese give the U.S. president a sword-guard vase

President William Howard Taft visited the AYP Exposition on Taft Day, September 30th. It was the first visit to Seattle by a sitting U.S. president and would be the last for many decades to come.

Naturally, many individuals and groups wished to meet him during his visit. One of the most unexpected groups was the Japanese Association of Washington State. Taft, former govermor-general of the Philippines, had had more personal contact with Asians than any earlier president but it was still surprising that a group of near-outcast Asian Americans dared to make demands on his valuable time.

The Association's members must have met him during his tour of the AYPE fairgrounds, where their own Japanese Village and the official Japan Building were both major attractions. The Association ensured that the meeting would be remembered by presenting Taft with a gift that an art-loving president (his brother, Charles, was the founder of the Taft Art Museum in Cincinnati) would not discard or give away -- a fine (and expensive) copper alloy vase in typical Meiji style.

The ornaments on the vase are of the kind produced by tsuba (sword guard) makers, many of whom turned to vases and similar products after the carrying of swords was outlawed in Japan during the early Meiji period (1867-1912). The copper-base alloy vase is inlaid with pure gold, shakudo (a black gold alloy), and shibuichi (a gray silver alloy), depicting a pair of chickens, a crow, and flowers. An English-language inscription on the base reads: