Chinese in Northwest America Research Committee (CINARC)

This page was last updated: August 30, 2018

(UNLESS OTHERWISE STATED ALL DATA ON THIS PAGE COMES FROM THE EDITORS' OWN RESEARCH ON PRIMARY SOURCES & ARTIFACTS)

ARTIFACTS 实物一览

This page presents systematic lists of data of a kind that may seem more relevant for archaeologists and material culture oriented historians than for students of Chinese American/Canadian culural and social history. However, as with the opium cans and pipes discussed elsewhere on this website, detailed information about artifact dates and distributions is an essential and often neglected basis for interpreting the past. Even as late as 1900, many aspects of Chinese life in the Northwest and other parts of the Americas were never recorded in writing and too early for first-hand oral recollection. The only way we can begin to understand those aspects is to study the objects that have been left behind in homes, storerooms, museums, and archaeological sites.

Shiwan (Foshan) Potters' Guild Names and Main Products (all photos are from the Shiwan Ceramic Museum in Foshan)

1. Large Basin Guild 大盆行.

Deep basins of various shapes and glaze. A number of 20th

century large jars with lugs and handles are considered to be

products of this guild too, illustrating how fluid a guild's

jurisfictioncan could be.

2. Gang Jar Guild 缸行.

Wide-mouthed jars for sugar, tea, congee, rice grains, etc.

3. Cheng Jar Guild 埕行.

Large & small jars, restricted at both ends with a much expanded

middle part, for wine, vinegar, oil, garlic, pickled vegetables, etc.

4. Bian Rice Cooker Guild 边钵行.

Basically a small bowl with an unglazed exterior and two lifting

ears on the rim or a casserole-like handle.

5. Horizontal-Ear Rice Cooker Guild 横耳行.

Congee boilers with a side handle.

6. Tea Kettle Guild 茶煲行.

Tea kettles with pouring spout and a parallel or right-angled handle

for making herbal or medicinal teas, usually unglazed outside.

7. Bo Bowl Guild 钵行.

Serving bowls with rim and base of comparable diameter.

8. White Glaze Guild 白釉行.

Household objects such as pillows, chopstick holders,

spittoons, brush holders, canters, shallow flower containers, etc.

many with low-fied white lead glaze and green copper-lead

glaze.

9. Black Glaze Guild 黑釉行.

This guild's products include many types of vessels with black or dark

brown glaze. Among these vessels are small to medium sized types

including lidded bowls, vase-like wine bottles, ginger grinders, ink

grinding palettes, jars of many shapes, etc.

10. Red Glaze Guild 红釉行.

Altar Items with red glaze incense burners, candelsticks, lamp

stands, oil lamps, etc.

11. Antique Guild 古玩行.

Decorative figures of human, animal, and architecture, glazed

or unglazed, often sought after by collectors.

12. Ta Jar Guild 塔行.

Jars with a rim diameter smaller than its base, for flour or bean

curd.

13. Flower Pot Guild 花盆行.

Flower pots, lattice squares, tiles, water pipes, balustrades,

large garden water jars, etc.

14. Saggered Ware Guild大冚行.

Containers of various kinds, including shapes very similar to

those of Cheng-jars of No .3. Because they were fired in

saggers, the finish of their glaze appear to be even and

smooth, often with the rim fully covered with glaze.

15. Face Basin Guild 面盆行.

Flat basins with glazed inside for holding water to wash hands

and faces.

16. Teapot Guild 茶壶行.

Tall teapots, many cylindrical for padded tea baskets, with

various glazes, including blue and white.

17. Lid-and-Plate Guild 盏碟行.

Lids for jars and cup lamps.

18 & 19. Flattened & Tall Bo Jar Guilds 高-扁博行.

Unglazed large jars for industrial purposes such as indigo

boiling, meat stock preparation, or remporary storage of fluid

compost.

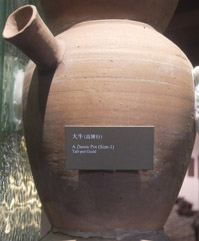

20. Diao Water Jar Guild 水铫行.

Large sturdy jars with a short spout and a small handle for

serving water or tea.

21. Lamp Guild 尾燈行.

Censers, candle sticks, lamps.

22. Golden Box Guild 金箱行

Ceramic coffins, mainly for chldren.

23. Live Gold Guild 生金行

Urns for secondary burials, important in southern Chinese

2. Gang jars

3. Cheng jar

4. Bian rice cooker

5. Congee boiler

6. Herbal tea kettle

7. Bo serving bowl

8. White Glaze Guild vessels

9. Black Glaze Guild liquor bottles

10. Red Glaze Guild objects

11. See Google Images

of "Shek Wan" and "Shiwan" figurines

12. Ta jars

14. Saggered Ware Guild jar with spout, viewed from above

13. See Google Images

of "Shek Wan" and "Shiwan" flower pots

15. Face Washing Basin

Guild mid-sized basins

16. Teapot Guild. Teapots for tea baskets

9. Black Glaze Guild sanping and daping covered containers ("boxes")

1. Large basin

20. Diao Water jar

19. Tall Bo jar

21. Lamp

The Products of the Foshan Potters' Guilds 石湾制陶业行会

The kilns of Shiwan 石湾 or Shekwan in Foshan 佛山, south of Guangzhou and strategically positioned in the heartland of the samyup 三邑 area on the main waterways that connected Guangzhou with Hong Kong and the outside world, supplied much of the heavily potted, inexpensive glazed stoneware used by American Chinese in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Although Shiwan is famous for its flambé-glazed ceramic figurines, its workshops and factories were mainly focused on utilitarian wares: jars, cooking and serving pots, pitchers, teapots, basins, liquor bottles, flower pots, plates, storage containers, and so forth in solid black, brown, and green colors.

With hundreds of active kilns plus southern China's main concentration of iron foundries as well as large-scale silk winding and weaving in the surrounding countryside, the Foshan area ranked with the largest industrial centers in the world before 1800. By the time Chinese emigrants first reached North America in 1850, the Euro-American Industrial Revolution had cut severely into the export business of Foshan's iron makers although they did still export many iron temple bells and censers (click here for examples). However, its traditional ceramic manufacturers hung on for decades longer. The sheer scale of production, technical expertise, key location, and web of export connections of Foshan's ceramic makers meant that Chinese cooks and restaurant owners in North America could hardly have avoided using Shiwan wares even if they wanted to. One expects to find that most plain-colored utilitarian wares in early Chinatowns were made in Shiwan. It would be surprising if they were not.

.

As in the case of many other traditional industries in pre-modern China, the Shiwan potters had organized themselves into guilds for several centuries before America became one of their global markets. These guilds, evolved from just a few in the 17th century to 24 in the late 19th century and to about 35 in 1940s. Each claimed a monopoly on certain kinds of stonewares.

In the new Guangdong Shiwan Ceramics Museum 广东石湾陶瓷博物馆 there are displays that illustrate some ware types of various sizes made by each guild. Many of these utilitarian wares found their way to North America, as shown by the images of Port Townsend and Williams Lake ceramic finds in the following article.

Numerous as they are, these Chinese black or brown glazed pots have sadly not often been collected by either art or ethnic museums in America. An exhibition in 2013 in Michigan was a welcome exception. Chinese Folk Pottery Exhibition was held at the Museum of Art at University of Michigan. Its accompanying catalogue shows several types that could be relevant to early Chinese immigrants to North America. Another exception is the Chinese Pioneer Virtual Museum, which offers photos of many ceramics from Chinese mining sites in British Columbia.

Foshan and the ceramics of Shiwan01/14/2015

Potters' guild names and main products01/14/2015

Chinese temple carving makers in Guangzhou 06/19/2013

Opium pipe bowls from Shiwan and Yixing10/19/2009

(Artifacts from all of the above occur at Chinese sites in the U.S. and Canada)

The Mall finds show that local Chinese drank wujiapi 五加皮 [five-plus-skin] and meiguilu 玫瑰露 [rose dew], both of them liquor distilled from kaoliang sorghum. The grain called kaoliang was grown, fermented, and distilled in northern China, after which it was shipped south in large containers to Guangdong. Companies there added medicinal ingredients like ginseng (and in the case of meiguilu, rose essence), bottled the product, labeled it, and shipped it overseas. Many companies took part. One of the most important for the American trade was the Wing Lee Wai Company 永利威 , founded in Guangzhou in 1876 and soon with branches in many parts of China. Since the 1930s the headquarters of Wing Lee Wai has been in Hong Kong.

Some Chinese liquor reached America packed in larger jars like one in the Chinese Virtual Museum collection in Williams Lake, B.C. shown below (see also www.chinesecol.com/treasure.html). The jar once held distilled rice wine from 聚隆 Brewery in Jiujiang 九江, south of Guangzhou. The cheng-jar itself was probably a Foshan ware. Its size indicates that some Chinese merchants sold alcoholic drinks by the cup rather than by the bottle, as often was the case with the gaoliang liquors..

Brown/Black (Shiwan?) Wares from Port Townsend 华州钵党顺 出土佛山陶瓷

The photographs below are included here to show that wares very similar to those from Shiwan do occur at Chinese sites in Northwest America. One such site is Port Townsend in Washington, at the end of the Strait of Juan de Fuca, close to Canada, and on the main water route to Seattle and Tacoma. The city once had a substantial Chinatown [click here for more on Port Townsend).

Among the few traces left of that community are a collection of excavated objects discovered by accident in April, 1990, when the owners of the Port Townsend Antique Mall on Washington Street enlarged their basement. The digging revealed a quantity of Chinese materials, probably a waste heap at the edge of the the former tidal flats on which Chinatown had been built. The owners of the mall, recognizing the historical value of the collection, have put it on permanent display in the basement of the mall.

The finds were the usual sort of assemblage seen at late 19th century Chinese urban sites – ceramic kitchen and table wares, glass medicinal vials, opium related objects made of glass, ceramics, or tin, coins, etc. The ceramics include heavily potted ceramic vessels, often glazed brown or black, and sometimes bright green.

Similar wares were made at numerous kiln centers in China. Many of the pots and jars used in by Guangdong emigrants, who included almost all early Chinese in North America, came from the kilns of Shiwan in Foshan at the top of the Pearl River Delta in Guangdong. Shiwan was by far the largest ceramic producer in that region and exported pots and jars in massive quantities.. Are the pieces shown here from there? Many items used in places like Port Townsend look very much like the Shiwan products shown above. But some could have been made elsewhere. One would need a major program of chemical analysis to be sure.

Apart from wine, Port Townsend Chinese used squat jars with a small opening on top and a short spout. These must have served for pouring liquids like soy sauce and vinegar.

For storing dry or paste-like substances, local cooks and householders had several kinds of lidded cylindrical jars. Shown here are two liddded jars, one brown and one green, recovered from the Mall. Such jars are found in various sizes at most Chinese sites. They were used in the kitchen for keeping salt, sugar, or other condiments. They also could hold pastes, lotions, and the very small ones even possibly for opium. The inscriptions on the bottom of the brown jar "Jixing 锦兴" and the green one "Jinyuan 进源," probably indicate the names of workshops or other related businesses.

Ceramics from the Antique Mall site, Port Townsend

Jar for Jiujiang liquor, with the name in through-glaze sgraffiato on the shoulder. Chinese Pioneer Virtual Museum, Williams Lake, BC

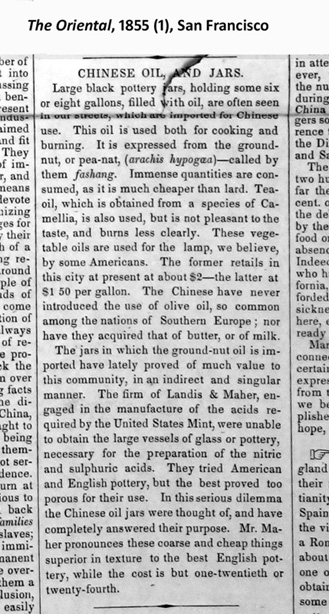

1855: Shiwan-style Ceramics Come to and are Valued in San Francisco

This clipping is from the first issue of The Oriental (Tung Ngai San-Luck), edited by William Speer and Lee Kan and printed in a bilingual format with articles in Chinese and English. The date is 4 January 1855. That makes it the second Chinese-language newspaper published in the U.S. (the short-lived Golden Hills News appeared and then disappeared in 1854) and one of the oldest printed Chinese-language newspapers in the world.

The article says that large quantities of peanut oil in large black-glazed jars were being imported by Chinese traders in San Francisco. The jars were being re-used by European-Americans in an unexpected way -- as containers for the acids used in the process of making gold coins at the recently established San Francisco branch of the United States mint.

According to the article, the mint "tried American and English pottery, but the best proved too porous for their use. In this serious dilemma the Chinese oil jars were thought of, and have completely answered the purpose. Mr. Maher (the acid manufacturer) pronounces these coarse and cheap things superior in texture to the finest English pottery, while the cost is but one-twentieth or twenty-fourth."

The jars probably came from Shiwan. The article attests to the advanced ceramic technology employed there and at other Chinese kiln centers. It took several more decades for European kilns to learn to make ceramic bodies as non-porous as the "coarse and cheap things" from China.

| ||||

A copy of the very rare inaugural issue of The Oriental is preserved at the Center for Sacramento History, in Sacra-mento. The editors were allowed to view it by the CHS's archivist, Patricia Johnson. We are grateful for the help given, time taken, and intelligent interest shown by her and other members of the CSH's staff.