Chinese in Northwest America Research Committee (CINARC)

This page was last updated: April 21, 2022

(UNLESS OTHERWISE STATED ALL DATA ON THIS PAGE COMES FROM THE EDITORS' OWN RESEARCH ON PRIMARY SOURCES & ARTIFACTS)

Coming Home in Gold Brocade: Chinese in Early Northwest America

PREFACE

The “Northwest America” of the title was the name of a ship built by Chinese craftsmen on Vancouver Island in 1788—the first Chinese artifact known to have been made in the Western Hemisphere. We chose to use the term in the title because it refers unambiguously to the area covered by the book: southern Alaska, British Columbia, Washington, Idaho, western Montana, and Oregon. Another name for the same region, “Pacific Northwest,” is time-honored in the U.S. but likely to confuse Canadians, for whom the same region is the West and Southwest. And to Asians and Europeans it is wrongheadedly Americentric. For them, the Pacific Northwest is Siberia and perhaps Korea and Japan.

The “Northwest America” of the title was the name of a ship built by Chinese craftsmen on Vancouver Island in 1788—the first Chinese artifact known to have been made in the Western Hemisphere. We chose to use the term in the title because it refers unambiguously to the area covered by the book: southern Alaska, British Columbia, Washington, Idaho, western Montana, and Oregon. Another name for the same region, “Pacific Northwest,” is time-honored in the U.S. but likely to confuse Canadians, for whom the same region is the West and Southwest. And to Asians and Europeans it is wrongheadedly Americentric. For them, the Pacific Northwest is Siberia and perhaps Korea and Japan.

Early Chinese immigrants seem to have viewed the northwestern part of North America as a single geographical unit: different from California, internally similar in terms of climate and topography, and more accessible than other parts of the North and South American continents. The majority of those immigrants, especially those who arrived before 1882, seem not to have paid undue attention to national, provincial, or state boundaries. They moved around as freely as they could, being always on the lookout for greener pastures like any other pioneers. We have tried to look at the region in the same way as those early immigrants saw it, tracing their successes and failures on as large a screen as possible.

Early Chinese immigrants seem to have viewed the northwestern part of North America as a single geographical unit: different from California, internally similar in terms of climate and topography, and more accessible than other parts of the North and South American continents. The majority of those immigrants, especially those who arrived before 1882, seem not to have paid undue attention to national, provincial, or state boundaries. They moved around as freely as they could, being always on the lookout for greener pastures like any other pioneers. We have tried to look at the region in the same way as those early immigrants saw it, tracing their successes and failures on as large a screen as possible.

We considered including the northern part of California but decided that another volume would be needed to extend that far south. We also decided that it might be better to distinguish the history of Chinese in California from that of Chinese in other parts of the New World. Writers on Chinese America tend to treat California as the norm, with Chinese culture in other regions representing watered-down versions of that of San Francisco. That is certainly how San Franciscan Chinese felt. And yet for other Chinese there were major differences between the Bay Area and the rest of the continent. Living outside Dai Fow, the “Great Port City,” needed not only courage but an innovative attitude. The challenges of living north and east of California required new institutions and economic patterns which did not much resemble those of the Bay Area. It is an error to see the rest of North America as the tail and San Francisco the dog.

We considered including the northern part of California but decided that another volume would be needed to extend that far south. We also decided that it might be better to distinguish the history of Chinese in California from that of Chinese in other parts of the New World. Writers on Chinese America tend to treat California as the norm, with Chinese culture in other regions representing watered-down versions of that of San Francisco. That is certainly how San Franciscan Chinese felt. And yet for other Chinese there were major differences between the Bay Area and the rest of the continent. Living outside Dai Fow, the “Great Port City,” needed not only courage but an innovative attitude. The challenges of living north and east of California required new institutions and economic patterns which did not much resemble those of the Bay Area. It is an error to see the rest of North America as the tail and San Francisco the dog.

We have focused here on the early decades of the Chinese presence on the Northwest, with 1911—the year of the Chinese Revolution—as the cutoff point. Those first decades are crucially important but poorly studied. Published information about them is hard to get even though understanding them is essential for studies of later developments in the American Chinese world. With several notable exceptions, the historiography of the Chinese American Northwest tends to be focused on single places or issues, based largely on secondary sources, and assembled by writers who had overly tight deadlines, limited access to original data, and an imperfect command of nineteenth century written Chinese.

We have focused here on the early decades of the Chinese presence on the Northwest, with 1911—the year of the Chinese Revolution—as the cutoff point. Those first decades are crucially important but poorly studied. Published information about them is hard to get even though understanding them is essential for studies of later developments in the American Chinese world. With several notable exceptions, the historiography of the Chinese American Northwest tends to be focused on single places or issues, based largely on secondary sources, and assembled by writers who had overly tight deadlines, limited access to original data, and an imperfect command of nineteenth century written Chinese.

We have tried to remedy those defects. For one thing, we have relied mainly on primary, first-hand sources. We have visited most of the archives that hold relevant English- and Chinese-language materials as well as most of the museums and traditional organizatios that own relevant objects with American Chinese inscriptions. Further, for us as for other researchers, the availability of on-line, searchable versions of historical newspapers and magazines has not only yielded vast quantities of new primary data but has also made it possible for the first time to draw conclusions based on negative evidence. Before the digital revolution, the seeming absence of an institution or individual from a given period or place meant only that one could not find relevant information. But now, with these vast and easily searchable databases, negative evidence has become logically valid. One is justified, for instance, in concluding that someone who often appeared in newspapers before 1890, but never afterward, either had left the country or was dead.

We have tried to remedy those defects. For one thing, we have relied mainly on primary, first-hand sources. We have visited most of the archives that hold relevant English- and Chinese-language materials as well as most of the museums and traditional organizatios that own relevant objects with American Chinese inscriptions. Further, for us as for other researchers, the availability of on-line, searchable versions of historical newspapers and magazines has not only yielded vast quantities of new primary data but has also made it possible for the first time to draw conclusions based on negative evidence. Before the digital revolution, the seeming absence of an institution or individual from a given period or place meant only that one could not find relevant information. But now, with these vast and easily searchable databases, negative evidence has become logically valid. One is justified, for instance, in concluding that someone who often appeared in newspapers before 1890, but never afterward, either had left the country or was dead.

It has long been fashionable among writers on early Chinese Americans to view them in terms of victimization, emphasizing the negative effects of dehumanizing immigration laws, anti-Chinese attitudes, threats, insults, and outright violence. We agree that those were indeed pervasive, deep-seated problems. We also feel the need to remind our fellow Northwesterners that our liberal, ethnically sensitive, politically correct region has not always been that way. Instead, in the late 19th century, it was in the forefront of American intolerance and vicious persecution of Chinese as well as other non-white peoples. This needs to be said. Yet we find ourselves tiring of victim narratives and think that Chinese-American historiography is not greatly in need of more.

It has long been fashionable among writers on early Chinese Americans to view them in terms of victimization, emphasizing the negative effects of dehumanizing immigration laws, anti-Chinese attitudes, threats, insults, and outright violence. We agree that those were indeed pervasive, deep-seated problems. We also feel the need to remind our fellow Northwesterners that our liberal, ethnically sensitive, politically correct region has not always been that way. Instead, in the late 19th century, it was in the forefront of American intolerance and vicious persecution of Chinese as well as other non-white peoples. This needs to be said. Yet we find ourselves tiring of victim narratives and think that Chinese-American historiography is not greatly in need of more.

For that reason, we have sought to see the early generations of Chinese immigrants as much more than victims. We have included the winners as well as the losers, the successful businessmen as well as the oppressed workers, and the respectable housewives along with the prostitutes. Moreover, we are not convinced that the oppressed workers were always to be pitied rather than admired. Many showed extraordinary strength, courage, and skill at adapting to an alien land. The story of their survival and eventual success deserves more space than that of their occasional misery.

For that reason, we have sought to see the early generations of Chinese immigrants as much more than victims. We have included the winners as well as the losers, the successful businessmen as well as the oppressed workers, and the respectable housewives along with the prostitutes. Moreover, we are not convinced that the oppressed workers were always to be pitied rather than admired. Many showed extraordinary strength, courage, and skill at adapting to an alien land. The story of their survival and eventual success deserves more space than that of their occasional misery.

This volume cannot explore any one topic in depth. A number of existing publications are more detailed, although sometimes out of date, in their coverage of Chinese in particular places or industries. Our purpose here is to work toward a broad perspective covering the whole Northwest and its connections with other regions and China itself. Readers wanting more information on the topics discussed here are urged to consult the website of the Chinese in Northwest America Research Committee, www.cinarc.org. Created in 2008 and edited by the present authors, the website has grown to a point where it now holds much more information than any single book.

This volume cannot explore any one topic in depth. A number of existing publications are more detailed, although sometimes out of date, in their coverage of Chinese in particular places or industries. Our purpose here is to work toward a broad perspective covering the whole Northwest and its connections with other regions and China itself. Readers wanting more information on the topics discussed here are urged to consult the website of the Chinese in Northwest America Research Committee, www.cinarc.org. Created in 2008 and edited by the present authors, the website has grown to a point where it now holds much more information than any single book.

The fact that this book has Internet roots explains several of its special features. It uses many more pictures than the majority of academic works, and places those pictures closer to the part of the text that they illustrate. It has a fuller table of contents and index than do most present-day books. And it seeks to make the usual scholarly apparatus more efficient and less burdensome. The endnotes are numbered in a single series to avoid the confusion caused by having notes with the same number from different chapters. References have been streamlined. In an age when extensive bibliographic data is available with a few computer keystrokes, it seems pointless always to include the names of the publisher, city, and series, or lengthy titles for all books and articles. Instead, unless a more detailed citation is needed for clarity, the endnotes give only the author’s name, date, shortened title, and page number of the work in question. Also in the interests of streamlining, we have not included a conventional bibliography of works cited. In place of such a bibliography is a separate index of authors and informants keyed to individual endnotes.

The fact that this book has Internet roots explains several of its special features. It uses many more pictures than the majority of academic works, and places those pictures closer to the part of the text that they illustrate. It has a fuller table of contents and index than do most present-day books. And it seeks to make the usual scholarly apparatus more efficient and less burdensome. The endnotes are numbered in a single series to avoid the confusion caused by having notes with the same number from different chapters. References have been streamlined. In an age when extensive bibliographic data is available with a few computer keystrokes, it seems pointless always to include the names of the publisher, city, and series, or lengthy titles for all books and articles. Instead, unless a more detailed citation is needed for clarity, the endnotes give only the author’s name, date, shortened title, and page number of the work in question. Also in the interests of streamlining, we have not included a conventional bibliography of works cited. In place of such a bibliography is a separate index of authors and informants keyed to individual endnotes.

Various themes in the current book deserve a more in-depth treatment. The CINARC website has begun to do that. However, within the next few years we hope to produce other books on more closely targeted subjects: Chinese temples, tongs or secret societies, burials and the repatriation of bones, cannery work and contracting, Chinese gold mining, and so forth. Until then, we trust that the present reader will find interest in what we have written here.

Various themes in the current book deserve a more in-depth treatment. The CINARC website has begun to do that. However, within the next few years we hope to produce other books on more closely targeted subjects: Chinese temples, tongs or secret societies, burials and the repatriation of bones, cannery work and contracting, Chinese gold mining, and so forth. Until then, we trust that the present reader will find interest in what we have written here.

A note on Chinese characters. We have deliberately used a mixture of traditional and simplified forms in deference to individual preferences with regard to personal names and because simplified versions of certain place names are incomprehensible to those with traditional educations.

A note on Chinese characters. We have deliberately used a mixture of traditional and simplified forms in deference to individual preferences with regard to personal names and because simplified versions of certain place names are incomprehensible to those with traditional educations.

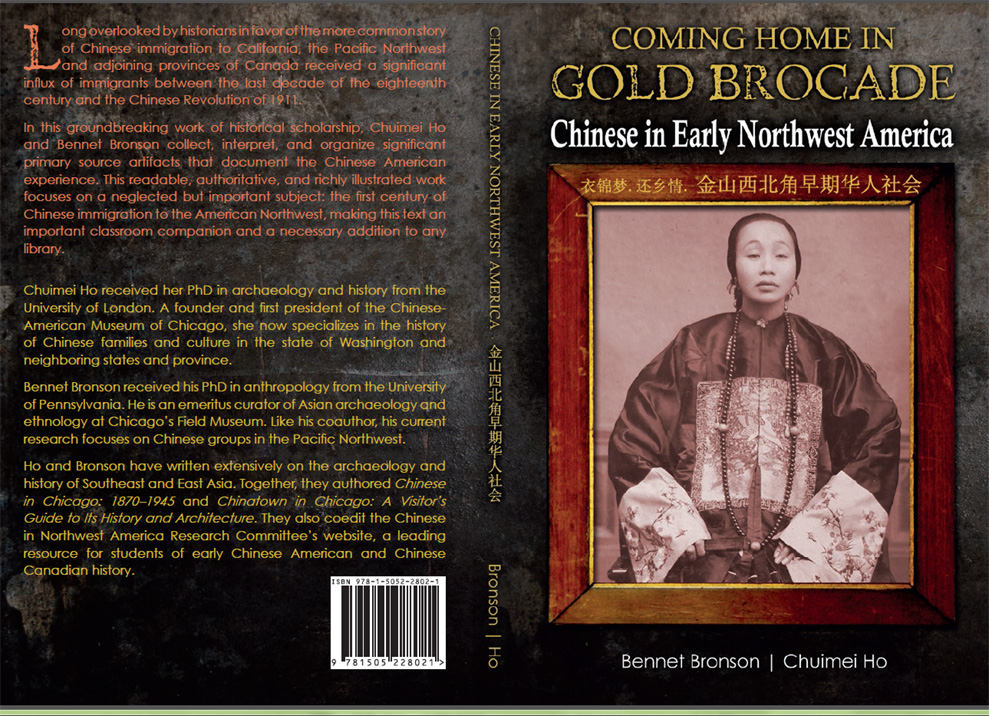

1. Cover The Front and back covers, plus the spine.

3. Preface The book's preface in final form.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER 1: THROUGH CHINESE EYES

1.0. Introduction: Why They Came

1.1. The View from the Villages

1.4. North American Chinese View Themselves

Countering Perceptions of Cultural Inferiority

Countering Perceptions of Cultural Inferiority

Public Displays of Cultural Pride

Public Displays of Cultural Pride

CHAPTER 2: PATTERNS IN TIME, SPACE, & POPULATION

2.0. Introduction: Six Phases

2.1. Before 1850: Early Adventurers

Vancouver Island: Chinese with Meares, 1788

Vancouver Island: Chinese with Meares, 1788

Cape Flattery, Washington: First Chinese on U. S. Soil?

Cape Flattery, Washington: First Chinese on U. S. Soil?

Vancouver Island: Chinese with Colnett, 1789

Vancouver Island: Chinese with Colnett, 1789

Chinese on Other Western Ships, 1790s

Chinese on Other Western Ships, 1790s

Haida Gwaii or Alaska –Xie Qinggao’s Account

Haida Gwaii or Alaska –Xie Qinggao’s Account

Other Possible Arrivals before 1850

Other Possible Arrivals before 1850

2.2. 1850s-1870: Miners and Merchants in the First

Chinese Mining Settlements in the Interior

Chinese Mining Settlements in the Interior

Chinese Commercial Settlements on the Coast

Chinese Commercial Settlements on the Coast

Chinese in Coastal Industries

Chinese in Coastal Industries

First Signs of Prejudice and Violence

First Signs of Prejudice and Violence

2.3. 1870-1885: A Demographic and Economic Peak

Chinese Flourish in the Northwest

Chinese Flourish in the Northwest

Influence of Railroad, Cannery, and Mining Work

Influence of Railroad, Cannery, and Mining Work

Influence of Farming and Fishing Work

Influence of Farming and Fishing Work

Rise of Anti-Chinese Violence

Rise of Anti-Chinese Violence

2.4. 1885-1887: Hostility, Chaos, and Flight

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882

Organized Violence Begins: Anaconda, April 1885

Organized Violence Begins: Anaconda, April 1885

Rock Springs, September 1885

Rock Springs, September 1885

Squak and Coal Creek, September 1885

Squak and Coal Creek, September 1885

The Conspirators, 1885-1886

The Conspirators, 1885-1886

The “Tacoma Method,” November 1885

The “Tacoma Method,” November 1885

The Seattle Riot, February 1886

The Seattle Riot, February 1886

Violence Elsewhere in the Northwest, 1885-1886

Violence Elsewhere in the Northwest, 1885-1886

Snake River/Deep Creek, May 1887

Snake River/Deep Creek, May 1887

2.5. 1888-1900: Chinese Concentrate in Cities

Renewed Racism and Violence East of the Cascades

Renewed Racism and Violence East of the Cascades

Increasing Urbanization in Coastal Areas

Increasing Urbanization in Coastal Areas

2.6. After 1900: Future Trends

CHAPTER 3: ECONOMIC LIFE

3.0. Introduction: Employment in the Early Northwest

3.1. Merchants and Contractors

Individual Merchant Contractors

Individual Merchant Contractors

The Columbia River Canneries

The Columbia River Canneries

Ethnicity and Wages at Canneries

Ethnicity and Wages at Canneries

The Only First-Hand Account by a Chinese Cannery

The Only First-Hand Account by a Chinese Cannery

Why Chinese Railroad Builders Got No Credit for their Work

Why Chinese Railroad Builders Got No Credit for their Work

Chinese as Railroad Maintenance Workers

Chinese as Railroad Maintenance Workers

3.4. Chinese in Lumber Mills

3.5. Gold and Coal Miners

3.6. The Canadian Opium Industry

Opium as a Business: The 1886 Price War

Opium as a Business: The 1886 Price War

3.7. Chinese in the Restaurant Trade

3.9. Chinese in Domestic Service

3.11. Farmers and Gardeners

3.12. Commercial Services and Factory Work

CHAPTER 4: COMMUNITY STRUCTURE

4.0. Introduction: Associations and Records

The Bing Kung & Bow Leong Tongs

The Bing Kung & Bow Leong Tongs

4.2. County/District Associations

Shantang in Victoria and Vancouver

Shantang in Victoria and Vancouver

County/District Associations beyond Victoria and Vancouver

County/District Associations beyond Victoria and Vancouver

The Hakka Speech Group Association

The Hakka Speech Group Association

4.3. Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Associations

Roles of CCBAs in the Northwest

Roles of CCBAs in the Northwest

Portland’s Jong Wah & Co.

Portland’s Jong Wah & Co.

CCBAs in Victoria and Vancouver

CCBAs in Victoria and Vancouver

Seattle’s Chong Wa Benevolent Association

Seattle’s Chong Wa Benevolent Association

4.4. Clan or Surname Associations

Clan Associations in Victoria and Vancouver

Clan Associations in Victoria and Vancouver

The Chens/Chins and the Oak Tin in Seattle and Portland

The Chens/Chins and the Oak Tin in Seattle and Portland

Clan Associations outside the Main Urban Centers

Clan Associations outside the Main Urban Centers

4.5. Temples in Northwest America

Independent Multi-Deity Temples

Independent Multi-Deity Temples

Independent Temples for Suijing Bo

Independent Temples for Suijing Bo

An Independent Hakka Temple

An Independent Hakka Temple

Shrines of County/District Associations

Shrines of County/District Associations

The Decline of Traditional Shrines and Temples

The Decline of Traditional Shrines and Temples

4.6. Non-Traditional Organizations

The Chinese Empire Reform Association or Baohuanghui

The Chinese Empire Reform Association or Baohuanghui

The American-Born Chinese Brigade

The American-Born Chinese Brigade

Other Progressive Non-Traditional Groups

Other Progressive Non-Traditional Groups

4.7. Christian Churches and Mission Schools

CHAPTER 5: PRIVATE LIVES IN THE NORTHWEST

5.0. Introduction: Picturing Individuals in the Past

5.1. Chinese Men in the Northwest

in the Northwest

5.2. Chinese Women in the Northwest

The China-Born: Prostitutes/Entertainers

The China-Born: Prostitutes/Entertainers

The China-Born: Respectable Women

The China-Born: Respectable Women

5.3. Marriage and Intermarriage

5.4. Civil and Property Rights

5.8. Funerals, Burials, Memorials, and Repatriation

Wakes and Funerals in the Northwest

Wakes and Funerals in the Northwest

Repatriation and Reburial

Repatriation and Reburial

Contrasting Lives and Deaths: Lee Yau Kan vs Moy Back Hin

Contrasting Lives and Deaths: Lee Yau Kan vs Moy Back Hin

APPENDICES

1. How Many Chinese Died in Building the First transcontinental

2. Chinese Populations in Inland and Coastal Areas, 1870 & 1880

3. Chinese Women in Oregon, Idaho, and Washington from 1880

4. Chung Sai Yat Po on Substituting for the Authority of Absent

INDEX OF AUTHORS & INFORMANTS

TO SEE MORE OF THE TEXT, GO TO "COMING HOME IN GOLD BROCADE" OM AMAZON.COM AND CLICK ON "LOOK INSIDE." THAT WILL SHOW YOU THE FIRST 20+ PAGES AND SOMETIMES THE FIRST 100 PAGES, FOR FREE.

COMING HOME IN GOLD BROCADE

COMING HOME IN GOLD BROCADE

70

72

72

75

78

79

81

81

83

85

87

89

91

92

94

85

99

101

102

106

108

111

112

114

116

120

124

125

126

129

130

131

133

134

134

135

137

138

139

140

142

143

145

146

149

150

152

153

155

158

162

163

164

168

170

170

172

173

175

176

177

iii

iv

vii

ix

xiv

1

2

8

10

11

13

17

18

19

22

27

27

27

29

30

31

32

34

36

37

40

42

43

44

44

46

48

48

49

49

50

51

52

53

54

56

58

59

60

62

62

64

66

67

181

181

181

183

184

188

189

191

195

199

201

205

208

212

215

217

220

222

224

227

Chapter 1 without quotes, images, and notes

As a sample here is Chapter 1 of Coming Home in Giold Brocade. Images, etc.,have been omitted due to a lack of space and the difficulty of translating a PDF file to a format usable by this web-authoring program. Readers who are curious about sources or who disagree with statements made here should contact the authors or, if they haven't already, buy the book to see how we justify those statements. At $12.75, the book is not expensive.

CHAPTER 1: THROUGH CHINESE EYES

1.0. Introduction: Why They Came

One is often told that the first Chinese came to America because of famine or war in southern China, or in desperation due to abject poverty. But this is a Western perspective. While such motives may have been true of certain European immigrants—for instance, of Irish fleeing the Potato Famine—it was not true of Chinese immigrants in the 19th century. Most came from homes well above the contemporary Chinese poverty level. Few were in fact poverty-stricken, landless laborers. Moreover, their districts had been sending temporary emigrants—sojourners—overseas for centuries before the first would-be gold miners arrived in California in 1849.

One is often told that the first Chinese came to America because of famine or war in southern China, or in desperation due to abject poverty. But this is a Western perspective. While such motives may have been true of certain European immigrants—for instance, of Irish fleeing the Potato Famine—it was not true of Chinese immigrants in the 19th century. Most came from homes well above the contemporary Chinese poverty level. Few were in fact poverty-stricken, landless laborers. Moreover, their districts had been sending temporary emigrants—sojourners—overseas for centuries before the first would-be gold miners arrived in California in 1849.

Among the first Chinese miners to go abroad seeking gold were Hakkas, most if not all from Guangdong province, who began to develop the gold fields of Borneo during the eighteenth century. The first Chinese tin miners in southern Thailand, West Malaysia, and Belitung in Indonesia, using techniques similar to those of gold miners, left China in the late eighteenth century or perhaps before. Most were Cantonese, Taishanese, and Hakkas, also from Guangdong, as well as Hokkiens from southern Fujian. The two earliest county/district associations (huiguan) in Singapore, the Ning Yeung and Kong Chow Associations, were founded in the 1820s by migrants from the Pearl River Delta in Guangdong. Two of the most important huiguan in San Francisco, founded in 1853 and 1867, had the same names: the Ning Yung and Kong Chow Associations. Their members came from the same Taishanese-speaking districts in the Pearl River Delta, and often from the same towns and villages, as earlier emigrants from Guangdong to Southeast Asia.

Among the first Chinese miners to go abroad seeking gold were Hakkas, most if not all from Guangdong province, who began to develop the gold fields of Borneo during the eighteenth century. The first Chinese tin miners in southern Thailand, West Malaysia, and Belitung in Indonesia, using techniques similar to those of gold miners, left China in the late eighteenth century or perhaps before. Most were Cantonese, Taishanese, and Hakkas, also from Guangdong, as well as Hokkiens from southern Fujian. The two earliest county/district associations (huiguan) in Singapore, the Ning Yeung and Kong Chow Associations, were founded in the 1820s by migrants from the Pearl River Delta in Guangdong. Two of the most important huiguan in San Francisco, founded in 1853 and 1867, had the same names: the Ning Yung and Kong Chow Associations. Their members came from the same Taishanese-speaking districts in the Pearl River Delta, and often from the same towns and villages, as earlier emigrants from Guangdong to Southeast Asia.

It seems, therefore, that the earliest Chinese immigrants to North America cannot have been driven to emigrate by emergency conditions back home—that is, unless one assumes that the delta region of Guangdong was in a constant state of emergency from the eighteenth century onward. But that is simply untrue. By and large, the Pearl River Delta was well above the poverty line by international standards of those days: houses were large, diet was good, and most Delta residents were adequately clothed. One of the main reasons for this prosperity was the local tradition of sending young men to work overseas, much as South and Southeast Asian nations do nowadays.

It seems, therefore, that the earliest Chinese immigrants to North America cannot have been driven to emigrate by emergency conditions back home—that is, unless one assumes that the delta region of Guangdong was in a constant state of emergency from the eighteenth century onward. But that is simply untrue. By and large, the Pearl River Delta was well above the poverty line by international standards of those days: houses were large, diet was good, and most Delta residents were adequately clothed. One of the main reasons for this prosperity was the local tradition of sending young men to work overseas, much as South and Southeast Asian nations do nowadays.

Why did these youthful migrants go abroad and why did so many come to North America? Those are the main issues to be addressed in this chapter. Only rarely can we hear the migrants’ actual voices, for few of their words survive and in any case are drowned out by the strongly held opinions of early Western observers and modern commentators, Chinese and white alike. What were the migrants thinking when they left home? Did their wishes matter, or were they no more than pawns of greedy recruiters and callous contractors backed by secret society criminals? Were most of them ignorant bumpkins who knew nothing about the cold, hunger, and hatred they would face in the Gold Mountain, before it was too late? Did they realize that, as some aver, they would be living almost like animals, crowded into tiny quarters and given inadequate food, in desperate efforts to save enough from their coolies’ pay to feed their hungry families back home? Did they think this was actually true? Was it, or have those problems been exaggerated by modern commentators? Greatly exaggerated or only somewhat?

Why did these youthful migrants go abroad and why did so many come to North America? Those are the main issues to be addressed in this chapter. Only rarely can we hear the migrants’ actual voices, for few of their words survive and in any case are drowned out by the strongly held opinions of early Western observers and modern commentators, Chinese and white alike. What were the migrants thinking when they left home? Did their wishes matter, or were they no more than pawns of greedy recruiters and callous contractors backed by secret society criminals? Were most of them ignorant bumpkins who knew nothing about the cold, hunger, and hatred they would face in the Gold Mountain, before it was too late? Did they realize that, as some aver, they would be living almost like animals, crowded into tiny quarters and given inadequate food, in desperate efforts to save enough from their coolies’ pay to feed their hungry families back home? Did they think this was actually true? Was it, or have those problems been exaggerated by modern commentators? Greatly exaggerated or only somewhat?

Such questions are not often asked, and yet we think they are central to one’s understanding of early North American Chinese. The real issue is the extent to which those Chinese could determine their own fates. Historians of nineteenth century immigration sometimes treat the Chinese involved as passive victims, subject to forces beyond their control and profoundly ignorant of the systems in which they were trapped. And yet, as we can see from interviews and surviving letters, many immigrants were far from stupid, and they and their fellow villagers were not at all naive about the outside world. Although early Chinese workers in some places—for instance, Peru and Cuba—often had been kidnapped and sold like slaves, in North America almost all males (and a good many females as well) came voluntarily with open eyes. They knew what they were getting into. So did their families. As we said above, conditions at home were not so bad that they had to come. Yet they came anyway.

Such questions are not often asked, and yet we think they are central to one’s understanding of early North American Chinese. The real issue is the extent to which those Chinese could determine their own fates. Historians of nineteenth century immigration sometimes treat the Chinese involved as passive victims, subject to forces beyond their control and profoundly ignorant of the systems in which they were trapped. And yet, as we can see from interviews and surviving letters, many immigrants were far from stupid, and they and their fellow villagers were not at all naive about the outside world. Although early Chinese workers in some places—for instance, Peru and Cuba—often had been kidnapped and sold like slaves, in North America almost all males (and a good many females as well) came voluntarily with open eyes. They knew what they were getting into. So did their families. As we said above, conditions at home were not so bad that they had to come. Yet they came anyway.

1.1. The View from the Villages

One way of looking at Chinese emigration is to put oneself in the place of a villager in one of the many Pearl River communities that had long specialized in sending its sons abroad. Historians call such communities qiaoxiang. Residents of these were not landless laborers or “coolies” of the kind who frequented seaport cities and were too often kidnapped by recruiters for the mines and plantations of South America and the Caribbean. Instead, they probably owned or had rights to enough land to produce much of the family’s food, a spouse (sometimes more than one), several children who survived into adulthood, a few meat animals and a regular supply of vegetables and fish, houses that were not smaller or less comfortable than the homes of contemporary farmers and factory workers in Europe, large extended families, and even larger clans.

One way of looking at Chinese emigration is to put oneself in the place of a villager in one of the many Pearl River communities that had long specialized in sending its sons abroad. Historians call such communities qiaoxiang. Residents of these were not landless laborers or “coolies” of the kind who frequented seaport cities and were too often kidnapped by recruiters for the mines and plantations of South America and the Caribbean. Instead, they probably owned or had rights to enough land to produce much of the family’s food, a spouse (sometimes more than one), several children who survived into adulthood, a few meat animals and a regular supply of vegetables and fish, houses that were not smaller or less comfortable than the homes of contemporary farmers and factory workers in Europe, large extended families, and even larger clans.

Both extended family and clan would have been based in the immediate vicinity, the latter in several neighboring hamlets and the former in the same hamlet. Hamlet clusters and small to medium sized villages were often dominated by single clans, so that everyone there had the same surname. Because marrying a person with the same surname was considered incest and because residence was virilocal, with married couples expected to live in the husband’s village, wives invariably came from outside. Elsewhere in China, this meant that married women had little support from their own families and thus little authority until their sons, if any, reached maturity. In a qiaoxiang, however, many husbands and most of their male kin worked abroad for years on end. It followed that even a very young wife could find herself in charge of a substantial household, subject to the general authority of her husband’s extended family and clan but otherwise independent.

Both extended family and clan would have been based in the immediate vicinity, the latter in several neighboring hamlets and the former in the same hamlet. Hamlet clusters and small to medium sized villages were often dominated by single clans, so that everyone there had the same surname. Because marrying a person with the same surname was considered incest and because residence was virilocal, with married couples expected to live in the husband’s village, wives invariably came from outside. Elsewhere in China, this meant that married women had little support from their own families and thus little authority until their sons, if any, reached maturity. In a qiaoxiang, however, many husbands and most of their male kin worked abroad for years on end. It followed that even a very young wife could find herself in charge of a substantial household, subject to the general authority of her husband’s extended family and clan but otherwise independent.

The reverse side of this coin was loneliness. The wife of a temporary emigrant or sojourner to a foreign country might have lived with her husband for only a few months after their wedding and seen him for only one or two short periods before he returned to his home village for good, perhaps in middle age if he had been lucky and made enough money to retire early, perhaps in old age if he had survived and accumulated at least modest savings, or perhaps in death if he had not. In some cases, wives and husbands may have hardly known each other at all. This eased the pain of nearly life-long separation. In other cases, though, the couple had found the love that often followed an arranged marriage and missed each other sorely. Numerous poems known as Gold Mountain Songs survive, testifying to the suffering of lonely male sojourners and of their wives back home. For instance,

The reverse side of this coin was loneliness. The wife of a temporary emigrant or sojourner to a foreign country might have lived with her husband for only a few months after their wedding and seen him for only one or two short periods before he returned to his home village for good, perhaps in middle age if he had been lucky and made enough money to retire early, perhaps in old age if he had survived and accumulated at least modest savings, or perhaps in death if he had not. In some cases, wives and husbands may have hardly known each other at all. This eased the pain of nearly life-long separation. In other cases, though, the couple had found the love that often followed an arranged marriage and missed each other sorely. Numerous poems known as Gold Mountain Songs survive, testifying to the suffering of lonely male sojourners and of their wives back home. For instance,

Since my departure in Hong Kong,

She and I are each in different places.

She and I are each in different places.

A long separation makes a person even more miserable.

A long separation makes a person even more miserable.

How can one ever forget home, sweet home?

How can one ever forget home, sweet home?

Stranded in a foreign country,

Stranded in a foreign country,

In dreams my soul encircles my village home.

In dreams my soul encircles my village home.

Words to wife and children: don’t worry, you won’t have to wait too long.

Words to wife and children: don’t worry, you won’t have to wait too long.

Once I amass the gold, I will be on my way.

Once I amass the gold, I will be on my way.

from the University of North Carolina School of Education website,

http://soe.unc.edu/hoh/file.php?id=Chinese+Primary+Source+Documents...

http://soe.unc.edu/hoh/file.php?id=Chinese+Primary+Source+Documents...

The key, as the song says, was money. Remittances from overseas workers made a major difference to the wellbeing of families and villages. A modern example comes from recent studies of Jianglian, a qiaoxiang in Taishan [or Toisan] County, long the home base of many overseas workers in North America and Malaysia. It will be seen from the following graph (Fig. 1) that the incomes of households getting remittances from overseas sojourners were between 45% and 111% higher than households without such remittances.

The key, as the song says, was money. Remittances from overseas workers made a major difference to the wellbeing of families and villages. A modern example comes from recent studies of Jianglian, a qiaoxiang in Taishan [or Toisan] County, long the home base of many overseas workers in North America and Malaysia. It will be seen from the following graph (Fig. 1) that the incomes of households getting remittances from overseas sojourners were between 45% and 111% higher than households without such remittances.

. The obligation to remit is shown in the following exchange between a Customs inspector and Ng Gwong, a cook in Port Townsend, Washington, preserved in the files of the National Archives and Records Administration in Seattle.

The obligation to remit is shown in the following exchange between a Customs inspector and Ng Gwong, a cook in Port Townsend, Washington, preserved in the files of the National Archives and Records Administration in Seattle.

On May 6, 1907:

On May 6, 1907:

Inspector:

Inspector:  How much wages do you get a month?

How much wages do you get a month?

Inspector:

Inspector:  Then why don’t you save any money?

Then why don’t you save any money?

Ng Gwong:

Ng Gwong:  Because I send all my money back to China.

Because I send all my money back to China.

Several months later in 1908.

Several months later in 1908.

Inspector:

Inspector:  What did you do with the [borrowed] money?

What did you do with the [borrowed] money?

Ng Gwong:

Ng Gwong:  I sent it back to China to build a house.

I sent it back to China to build a house.

In the nineteenth century, when exchange rates and prices were such that a few American dollars would support a Chinese family for several months, the income gap between households with and without overseas sojourners was even wider than in modern Jianglian. If a railroad worker in the Northwest earned one U.S. dollar per day and if he spent a third of that on subsistence and half of the rest on recreation, he would still have been able to send a monthly remittance of ten U.S. dollars back to his family in Guangdong.

In the nineteenth century, when exchange rates and prices were such that a few American dollars would support a Chinese family for several months, the income gap between households with and without overseas sojourners was even wider than in modern Jianglian. If a railroad worker in the Northwest earned one U.S. dollar per day and if he spent a third of that on subsistence and half of the rest on recreation, he would still have been able to send a monthly remittance of ten U.S. dollars back to his family in Guangdong.

Considering that ten U.S. dollar coins equaled 240 grams of silver and that in 1880-1910 an unskilled urban worker in Guangzhou made the equivalent of only 100 grams of silver each month, a monthly remittance of just ten U.S. dollars was very good money. For many families, that much extra income would have been decisively important in terms of lifestyle and social status. It made the difference between being a common peasant and joining the rural middle class.

Considering that ten U.S. dollar coins equaled 240 grams of silver and that in 1880-1910 an unskilled urban worker in Guangzhou made the equivalent of only 100 grams of silver each month, a monthly remittance of just ten U.S. dollars was very good money. For many families, that much extra income would have been decisively important in terms of lifestyle and social status. It made the difference between being a common peasant and joining the rural middle class.

A moderately successful sojourner, of course, could remit much more than 100 grams of silver per month and could, if all went well, return with enough to make his extended family fabulously rich. Most such families cannot realistically have expected this. But, one imagines, some did, and this must have added to family pressure on young men to seek their fortunes overseas.

A moderately successful sojourner, of course, could remit much more than 100 grams of silver per month and could, if all went well, return with enough to make his extended family fabulously rich. Most such families cannot realistically have expected this. But, one imagines, some did, and this must have added to family pressure on young men to seek their fortunes overseas.

All this meant that residents of qiaoxiang did not think of themselves as subsisting on the voluntary gifts of sojourners inspired by love of family and innate generosity. Rather, families and fellow villagers must often have seen their overseas kin not as free agents but as investments, representing major sacrifices on the part of parents and clan. They might have subsidized a young relative’s outfitting and transportation costs. They certainly had not only paid for his upbringing but also had suffered the loss of his labor power and, perhaps, fighting skills during the long years of his absence. Centuries-old, deeply held social values came into play. To the sojourner’s family, remittances were a right, not a charity. He or she owed it to them, and failure to remit was tantamount to reneging on a debt.

All this meant that residents of qiaoxiang did not think of themselves as subsisting on the voluntary gifts of sojourners inspired by love of family and innate generosity. Rather, families and fellow villagers must often have seen their overseas kin not as free agents but as investments, representing major sacrifices on the part of parents and clan. They might have subsidized a young relative’s outfitting and transportation costs. They certainly had not only paid for his upbringing but also had suffered the loss of his labor power and, perhaps, fighting skills during the long years of his absence. Centuries-old, deeply held social values came into play. To the sojourner’s family, remittances were a right, not a charity. He or she owed it to them, and failure to remit was tantamount to reneging on a debt.

This helps to explain, incidentally, the insistent demands and lack of gratitude formerly said to be experienced by second-and third-generation overseas Chinese on returning to their ancestral villages. What modern visitors saw as aggressive panhandling was viewed by their hometown relatives simply as a reminder of obligations. The death of a first-generation emigrant did not extinguish such obligations. The memories of the villages were long, and they did not feel that a male relative’s marriage overseas and his raising a family there gave him any right to sever ancestral bonds. In fact, marrying overseas may have seemed in some ways to be a willful rejection of those bonds. The family back home felt betrayed.

This helps to explain, incidentally, the insistent demands and lack of gratitude formerly said to be experienced by second-and third-generation overseas Chinese on returning to their ancestral villages. What modern visitors saw as aggressive panhandling was viewed by their hometown relatives simply as a reminder of obligations. The death of a first-generation emigrant did not extinguish such obligations. The memories of the villages were long, and they did not feel that a male relative’s marriage overseas and his raising a family there gave him any right to sever ancestral bonds. In fact, marrying overseas may have seemed in some ways to be a willful rejection of those bonds. The family back home felt betrayed.

The threat of overseas marriages was always present, even in places like North America and Australia where racist laws against miscegenation were common and where, one would have thought, the higher status of available women, most but not all of them white, should have prevented their marrying lower-status Chinese. A later chapter points out that in fact not all white women or their families were so snobbish, but that is beside the point. What matters is that it was very much in a qiaoxiang family’s interest to make sure that its sons and nephews did not acquire other families, and consequent emotional and financial obligations, while working overseas.

The threat of overseas marriages was always present, even in places like North America and Australia where racist laws against miscegenation were common and where, one would have thought, the higher status of available women, most but not all of them white, should have prevented their marrying lower-status Chinese. A later chapter points out that in fact not all white women or their families were so snobbish, but that is beside the point. What matters is that it was very much in a qiaoxiang family’s interest to make sure that its sons and nephews did not acquire other families, and consequent emotional and financial obligations, while working overseas.

One way of doing this was to marry the boys off before sending them away and to keep the young wives back home. Modern Chinese writers sometimes complain bitterly about historic U.S. and Canadian immigration laws that they say barred Chinese wives from joining their husbands. But even when it was possible for wives to go abroad with their husbands and no matter what the couple themselves might have wished, the fact is that their elders in China were dead set against it. Wives were strongly discouraged from leaving, although for many years there were no legal obstacles to their accompanying their husbands. Chinese women could enter the United States freely until the 1882 Exclusion Act but very few came anyway. They remained scarce in Canada throughout the nineteenth century in spite of the fact that immigration was easy until the notorious but gender-neutral Head Tax became too costly in 1903. Chinese women were scarce even in Malaysia, which was inexpensive to reach from China by ship and where British colonial authorities actually encouraged them to come in the belief that married men with wives and families present made better, more law-abiding residents.

One way of doing this was to marry the boys off before sending them away and to keep the young wives back home. Modern Chinese writers sometimes complain bitterly about historic U.S. and Canadian immigration laws that they say barred Chinese wives from joining their husbands. But even when it was possible for wives to go abroad with their husbands and no matter what the couple themselves might have wished, the fact is that their elders in China were dead set against it. Wives were strongly discouraged from leaving, although for many years there were no legal obstacles to their accompanying their husbands. Chinese women could enter the United States freely until the 1882 Exclusion Act but very few came anyway. They remained scarce in Canada throughout the nineteenth century in spite of the fact that immigration was easy until the notorious but gender-neutral Head Tax became too costly in 1903. Chinese women were scarce even in Malaysia, which was inexpensive to reach from China by ship and where British colonial authorities actually encouraged them to come in the belief that married men with wives and families present made better, more law-abiding residents.

Thus, one key to retaining control of migrant boys was to keep the girls from leaving. It might be noted that southern Chinese emigrant villages were not the only ones to adopt this strategy. According to the website of Chicago's Hellenic Museum and Cultural Center,

Thus, one key to retaining control of migrant boys was to keep the girls from leaving. It might be noted that southern Chinese emigrant villages were not the only ones to adopt this strategy. According to the website of Chicago's Hellenic Museum and Cultural Center,

Greek immigration to the U.S. has been overwhelmingly male. During 1890-1900, one of the decades of the most

intense immigration, only four women arrived for every 100 men. Those who emigrated at this time often did so to

intense immigration, only four women arrived for every 100 men. Those who emigrated at this time often did so to

earn money to repay family debts, provide dowries for their sisters, and return to Greece with sufficient funds to live

earn money to repay family debts, provide dowries for their sisters, and return to Greece with sufficient funds to live

comfortably.

comfortably.

This explanation, given by Greeks writing about Greeks, is confirmed by Fairchild, writing in 1911. In that year, he says, New York’s Greek population consisted of 20,000 men and only 150 “unmixed” Greek families. The indicated ratio of fewer than one women to every 100 men was as extreme as in any early Chinatown.

Other factors too ensured that sojourners would send money while abroad and return when successful. Love for families played an important role. So did an upbringing that inculcated respect for such values as filial piety and loyalty to one’s home village and town. Moreover, as young villagers could see, adhering to those values was rewarded. Wealthier returnees were glorified, receiving local praise, honored places in their clans’ temples and genealogies, and special titles from the imperial government—see the example of Chin Gee Hee below (page 10). Hope for such happy outcomes must have kept many overseas sojourners working and remitting even when their living conditions and work environments were worse than anything back home.

Other factors too ensured that sojourners would send money while abroad and return when successful. Love for families played an important role. So did an upbringing that inculcated respect for such values as filial piety and loyalty to one’s home village and town. Moreover, as young villagers could see, adhering to those values was rewarded. Wealthier returnees were glorified, receiving local praise, honored places in their clans’ temples and genealogies, and special titles from the imperial government—see the example of Chin Gee Hee below (page 10). Hope for such happy outcomes must have kept many overseas sojourners working and remitting even when their living conditions and work environments were worse than anything back home.

Yet another way to ensure the loyalty of temporarily expatriated men was to provide a permanent resting place in the village cemetery. As pointed out in Chapter 5.8, Chinese sojourners in North America, though perhaps not in Southeast Asia, felt it was imperative to be buried in the soil of one’s home county and, if at all possible, of one’s home village. Was this only because it ensured that the deceased would receive the appropriate offerings from family members in memorial ceremonies? Or did most Chinese in those days believe that they had to be buried in China, irrespective of family considerations?

Yet another way to ensure the loyalty of temporarily expatriated men was to provide a permanent resting place in the village cemetery. As pointed out in Chapter 5.8, Chinese sojourners in North America, though perhaps not in Southeast Asia, felt it was imperative to be buried in the soil of one’s home county and, if at all possible, of one’s home village. Was this only because it ensured that the deceased would receive the appropriate offerings from family members in memorial ceremonies? Or did most Chinese in those days believe that they had to be buried in China, irrespective of family considerations?

Although there is little evidence that Chinese held such abstract beliefs before or after the period covered by this book (1850-1910), one does not doubt that workers newly arriving in North America were told that this was so, and that one of the main services to be provided to them in return for the dues exacted by the district associations, tongs, and other sojourner organizations was to send their bodies home in case of death. The elaborate system put in place to facilitate the repatriation of the dead is discussed in a later chapter (see pages 224-6). It is enough for now to point to the existence of that system. Sojourners of all ages must have felt encouraged to know that if they died while working in an alien land, their bones would be repatriated without fail, no matter how high the cost.

Although there is little evidence that Chinese held such abstract beliefs before or after the period covered by this book (1850-1910), one does not doubt that workers newly arriving in North America were told that this was so, and that one of the main services to be provided to them in return for the dues exacted by the district associations, tongs, and other sojourner organizations was to send their bodies home in case of death. The elaborate system put in place to facilitate the repatriation of the dead is discussed in a later chapter (see pages 224-6). It is enough for now to point to the existence of that system. Sojourners of all ages must have felt encouraged to know that if they died while working in an alien land, their bones would be repatriated without fail, no matter how high the cost.

1.2. Perceived Benefits

Advantages to the qiaoxiang included not only money for individual families but improvements in facilities and living conditions for the village as a whole. Successful overseas sojourners built better houses for themselves and their extended families. The more successful sojourners built houses that could be not only very large but in innovative styles, giving rise to a more sophisticated building industry.

Advantages to the qiaoxiang included not only money for individual families but improvements in facilities and living conditions for the village as a whole. Successful overseas sojourners built better houses for themselves and their extended families. The more successful sojourners built houses that could be not only very large but in innovative styles, giving rise to a more sophisticated building industry.

To villagers in insecure areas, which included large parts of the Four Counties or Si Yap on the west side of the Delta, an added benefit of the influx of overseas money was an increase in defensive capabilities. Many and perhaps most of that region’s diaolou 碉楼, homes with fortified towers, were built with overseas money. Although the syncretic Western-Chinese styles of many diaolou date them to the 1920s-30s, the first examples of such structures appeared in the 1890s-1900s or perhaps earlier.

To villagers in insecure areas, which included large parts of the Four Counties or Si Yap on the west side of the Delta, an added benefit of the influx of overseas money was an increase in defensive capabilities. Many and perhaps most of that region’s diaolou 碉楼, homes with fortified towers, were built with overseas money. Although the syncretic Western-Chinese styles of many diaolou date them to the 1920s-30s, the first examples of such structures appeared in the 1890s-1900s or perhaps earlier.

Successful sojourners often engaged in conspicuous charities aimed at populations larger than their families. The noted Portland-Seattle merchant

Successful sojourners often engaged in conspicuous charities aimed at populations larger than their families. The noted Portland-Seattle merchant

Goon Dip, for instance, not only contributed toward a family shrine in his village, Shangge, Meinam, Doushan, in southern Taishan County, but also had the village’s main street paved with concrete. Goon seems not to have been over-fond of Shangge. He left it as a boy, returned once to acquire a wife, and never came back again, directing that he be buried in Seattle rather than in the village cemetery. Yet he felt obliged to show loyalty anyway. The pavement and shrine he donated to the village ensured that his memory would be preserved in the clan records, which still survive. Younger villagers do not know his name. However, even they are vaguely aware that the pavement was financed by a fellow villager who became a success in “Gold Mountain.”

A much more spectacular and costly quasi-charitable effort was that of Chin Gee Hee of Seattle, who devoted the last decades of his long life to building a railroad connecting his native city, Taishan, with the Pearl River estuary and the sea. He had learned the railroad business working as a labor contractor for the Northern Pacific and various smaller lines. During his last years in America he seems to have felt that he knew enough to bill himself as a “railroad, mining, and telephone engineer.”

A much more spectacular and costly quasi-charitable effort was that of Chin Gee Hee of Seattle, who devoted the last decades of his long life to building a railroad connecting his native city, Taishan, with the Pearl River estuary and the sea. He had learned the railroad business working as a labor contractor for the Northern Pacific and various smaller lines. During his last years in America he seems to have felt that he knew enough to bill himself as a “railroad, mining, and telephone engineer.”

Chin’s self-confidence was justified. Although only modestly educated in a formal sense, his exceptional intelligence and business acumen made his Sun Ning Railway a success. It not only turned an occasional profit and helped to develop Taishan and its environs but also showed the world that Chinese could finance and build such major projects themselves, at a time when all other railroads in China were designed and owned by foreigners.

Chin’s self-confidence was justified. Although only modestly educated in a formal sense, his exceptional intelligence and business acumen made his Sun Ning Railway a success. It not only turned an occasional profit and helped to develop Taishan and its environs but also showed the world that Chinese could finance and build such major projects themselves, at a time when all other railroads in China were designed and owned by foreigners.

These two images sum up the rewards available to overseas sojourners who showed truly generous concern for their home towns. On the left is a statue of Chin Gee Hee, placed at a major intersection in downtown Taishan. On the right is a photograph of Chin wearing the surcoat and accessories to which he was entitled after becoming an honorary third-rank imperial official—one of the highest ranks achieved by any sojourner in North America.

These two images sum up the rewards available to overseas sojourners who showed truly generous concern for their home towns. On the left is a statue of Chin Gee Hee, placed at a major intersection in downtown Taishan. On the right is a photograph of Chin wearing the surcoat and accessories to which he was entitled after becoming an honorary third-rank imperial official—one of the highest ranks achieved by any sojourner in North America.

1.3. Official Attitudes

For ordinary people in the sojourner villages, the benefits of sending their young men abroad were obvious. However, for district and province-level officials in those parts of China, not to mention officials in the palace and ministries of Beijing, the situation was not so simple.

For ordinary people in the sojourner villages, the benefits of sending their young men abroad were obvious. However, for district and province-level officials in those parts of China, not to mention officials in the palace and ministries of Beijing, the situation was not so simple.

In the first place, the emigrants seemed to pose security risks. As noted in the next section, the old idea that all Chinese outside China were rebels or criminals proved to be hard to eradicate. Many officials, especially those from the North and other insular parts of China, continued to doubt the loyalty of all emigrants.

In the first place, the emigrants seemed to pose security risks. As noted in the next section, the old idea that all Chinese outside China were rebels or criminals proved to be hard to eradicate. Many officials, especially those from the North and other insular parts of China, continued to doubt the loyalty of all emigrants.

In the second place, the difficulties faced by overseas Chinese became an increasing distraction to an overworked, hidebound bureaucracy. Once the Qing government had accepted that emigrants could not just be dismissed as stateless outcasts, it became necessary to take at least minimal steps to protect them. Officials had to be trained to handle the diplomatic complexities involved, protecting national interests while dealing with racist, jingoistic attitudes in both China and the West. It did not help that career civil servants, still chosen through an exceptionally rigorous examination system, had high IQs but narrowly focused educations. Many came from parts of China where no one had seen a Westerner, had ever heard or seen a Western language, or knew anything at all about Western countries. The learning curve must often have been impossibly steep.

In the second place, the difficulties faced by overseas Chinese became an increasing distraction to an overworked, hidebound bureaucracy. Once the Qing government had accepted that emigrants could not just be dismissed as stateless outcasts, it became necessary to take at least minimal steps to protect them. Officials had to be trained to handle the diplomatic complexities involved, protecting national interests while dealing with racist, jingoistic attitudes in both China and the West. It did not help that career civil servants, still chosen through an exceptionally rigorous examination system, had high IQs but narrowly focused educations. Many came from parts of China where no one had seen a Westerner, had ever heard or seen a Western language, or knew anything at all about Western countries. The learning curve must often have been impossibly steep.

Government Suspicion

Chinese governments had long regarded Chinese outside China as security threats. Historians recognize that the Qing government, from 1850 through 1911, went through several stages of policy changes toward overseas Chinese, from negligence, to involvement, to protectiveness. Yet the suspicious attitude of officials toward Chinese abroad continued until the end of the regime. This view was not entirely unjustified.

Chinese governments had long regarded Chinese outside China as security threats. Historians recognize that the Qing government, from 1850 through 1911, went through several stages of policy changes toward overseas Chinese, from negligence, to involvement, to protectiveness. Yet the suspicious attitude of officials toward Chinese abroad continued until the end of the regime. This view was not entirely unjustified.

Whereas the great majority of emigrants were personally apolitical, they often belonged to secret societies with anti-Manchu agendas. The popular revolts that shook Guangdong province in the mid-nineteenth century, the Taiping Rebellion太平天囯 (1850-64) and the Red Turban Rebellion紅巾起義 (1854-56) had not only radicalized individuals but sharpened the long-standing anti-regime sentiments of the old secret societies. The imperial government believed that those societies had supported the fighting. In the case of the Red Turbans, officials were convinced that the Tiandi Hui 天地會 (Heaven and Earth Society) had both instigated the rebellion and provided much of its leadership. They also were well aware that the Tiandi Hui, also known as the Hong Society, had established itself in overseas areas like western North America. Some writers have suggested that the first secret societies—soon to be called “tongs”—in North America were founded by refugees from the fighting in Guangdong. But the Hong Society was first recorded in San Francisco by local newspapers in January, 1854, before the Red Turban Rebellion began.

Whereas the great majority of emigrants were personally apolitical, they often belonged to secret societies with anti-Manchu agendas. The popular revolts that shook Guangdong province in the mid-nineteenth century, the Taiping Rebellion太平天囯 (1850-64) and the Red Turban Rebellion紅巾起義 (1854-56) had not only radicalized individuals but sharpened the long-standing anti-regime sentiments of the old secret societies. The imperial government believed that those societies had supported the fighting. In the case of the Red Turbans, officials were convinced that the Tiandi Hui 天地會 (Heaven and Earth Society) had both instigated the rebellion and provided much of its leadership. They also were well aware that the Tiandi Hui, also known as the Hong Society, had established itself in overseas areas like western North America. Some writers have suggested that the first secret societies—soon to be called “tongs”—in North America were founded by refugees from the fighting in Guangdong. But the Hong Society was first recorded in San Francisco by local newspapers in January, 1854, before the Red Turban Rebellion began.

Interesting evidence of official suspicion that overseas Chinese communities were hotbeds of subversion is the letter reproduced on the next page, written by Yang Yu 杨儒, Chinese Minister (Ambassador) to the U.S. in 1897. Yang’s understanding of recent Chinese subversion seems to have focused on Shek Tat Hoy (石达开, Shi Dakai), a leader in the Taiping Rebellion. Yang was wrong, however, in thinking that Shi’s followers could have founded the Chee Kung Tong (致公堂, Zhigongtang, or CKT). That secret organization was present in California as the Hong Society long before “remnants” of the Taipings can have reached North America. However, Yang was quite right that Chan Manwai and Lee Hon (Cantonese: Lai Mon Hoy and Lee Cheuk Yon), both prominent in San Francisco’s Chinatown, were Chee Kung Tong leaders and that Sun Man (孫文,better known as Sun Yat-sen) was a seditious conspirator. Indeed, Sun, the first president of the Chinese Republic, was one of the most successful seditious conspirators in modern history. Yang was also right about Sun being associated with the Chee Kung Tong (although not the later Chinese Empire Reform Association—see page 172) as early as 1897, even though he is often said not to have joined the CKT until 1904.

Interesting evidence of official suspicion that overseas Chinese communities were hotbeds of subversion is the letter reproduced on the next page, written by Yang Yu 杨儒, Chinese Minister (Ambassador) to the U.S. in 1897. Yang’s understanding of recent Chinese subversion seems to have focused on Shek Tat Hoy (石达开, Shi Dakai), a leader in the Taiping Rebellion. Yang was wrong, however, in thinking that Shi’s followers could have founded the Chee Kung Tong (致公堂, Zhigongtang, or CKT). That secret organization was present in California as the Hong Society long before “remnants” of the Taipings can have reached North America. However, Yang was quite right that Chan Manwai and Lee Hon (Cantonese: Lai Mon Hoy and Lee Cheuk Yon), both prominent in San Francisco’s Chinatown, were Chee Kung Tong leaders and that Sun Man (孫文,better known as Sun Yat-sen) was a seditious conspirator. Indeed, Sun, the first president of the Chinese Republic, was one of the most successful seditious conspirators in modern history. Yang was also right about Sun being associated with the Chee Kung Tong (although not the later Chinese Empire Reform Association—see page 172) as early as 1897, even though he is often said not to have joined the CKT until 1904.

Ambassador Yang Yu on the Threat Posed by Chinese Emigrants, 1897

'California was formerly the refuge of the remnant of Shek Tat Hoy's long-haired rebels, who clandestinely

'California was formerly the refuge of the remnant of Shek Tat Hoy's long-haired rebels, who clandestinely

established the Chee Kung Tong and distributed heretical books, their idea being to plan revenge. Recently

established the Chee Kung Tong and distributed heretical books, their idea being to plan revenge. Recently

there also came the rebel Sun Man from Canton to America, and illicitly established the China Reform

there also came the rebel Sun Man from Canton to America, and illicitly established the China Reform

Association, printing rules calling people to join and take shares for the purpose of getting ready munitions

Association, printing rules calling people to join and take shares for the purpose of getting ready munitions

of war to send to Canton and again raise the standard of revolt. Chan Man Wai, Lee Hon You, that kind of

of war to send to Canton and again raise the standard of revolt. Chan Man Wai, Lee Hon You, that kind of

people have been for a long time residing beyond the seas with no law before their eyes. Whatever rebel-

people have been for a long time residing beyond the seas with no law before their eyes. Whatever rebel-

lious footprints of the Chee Kung Tong were exposed they have constantly followed and practiced. When

lious footprints of the Chee Kung Tong were exposed they have constantly followed and practiced. When

once Sun Man appeared they took rank as leaders. Sun Man has now gone to England, and this band of

once Sun Man appeared they took rank as leaders. Sun Man has now gone to England, and this band of

seditious conspirators cannot legally be extradited from any country where there is an extradition treaty.

seditious conspirators cannot legally be extradited from any country where there is an extradition treaty.

Moreover, to scatter their followers, the wings of the tongs must first be clipped. I, the Embassador, have

Moreover, to scatter their followers, the wings of the tongs must first be clipped. I, the Embassador, have

taken the Chee Kung Tong's villainous and heretical books and the China Reform Association's rules,

taken the Chee Kung Tong's villainous and heretical books and the China Reform Association's rules,

made an official examination and prepared this letter.

made an official examination and prepared this letter.

In any case, there can be no doubt that Yang was following the lead of his superiors in Beijing when he labeled the Chee Kung Tong as villainous and heretical. The 1890s saw a concerted effort by Chinese government representatives in California to wipe out all tongs. Most American Chinese belonged to one or another of those societies. The majority of their members did indeed harbor subversive ideas, adhering to the ancient Tiandi Hui motto, “Destroy the Qing, restore the Ming.” The average Chee Kung Tong member may not have been serious about restoring the Ming dynasty. But, as it turned out, the CKT would make major sacrifices to depose China’s Qing rulers and replace them with a western-style democratic government (see pages 172-173 and Chapter 4.1).

In any case, there can be no doubt that Yang was following the lead of his superiors in Beijing when he labeled the Chee Kung Tong as villainous and heretical. The 1890s saw a concerted effort by Chinese government representatives in California to wipe out all tongs. Most American Chinese belonged to one or another of those societies. The majority of their members did indeed harbor subversive ideas, adhering to the ancient Tiandi Hui motto, “Destroy the Qing, restore the Ming.” The average Chee Kung Tong member may not have been serious about restoring the Ming dynasty. But, as it turned out, the CKT would make major sacrifices to depose China’s Qing rulers and replace them with a western-style democratic government (see pages 172-173 and Chapter 4.1).

Towards the end of the 19th century, the Empress Dowager’s faction in the Chinese government had another reason to be suspicious about overseas Chinese. Since 1896, some members of the reformist faction of the government had begun openly to support the powerless Emperor over the Empress Dowager. This was going too far. The reformers fled abroad to preserve their heads. The founders of this group, Kang Youwei and Liang Qichao, made their way to Canada where they established the Chinese Empire Reform Association (CERA), seen as a major threat by the Empress’s regime. That many Chinese leaders in North America and Southeast Asia joined the CERA with enthusiasm did not endear any emigrant to conservatives in Beijing.

Towards the end of the 19th century, the Empress Dowager’s faction in the Chinese government had another reason to be suspicious about overseas Chinese. Since 1896, some members of the reformist faction of the government had begun openly to support the powerless Emperor over the Empress Dowager. This was going too far. The reformers fled abroad to preserve their heads. The founders of this group, Kang Youwei and Liang Qichao, made their way to Canada where they established the Chinese Empire Reform Association (CERA), seen as a major threat by the Empress’s regime. That many Chinese leaders in North America and Southeast Asia joined the CERA with enthusiasm did not endear any emigrant to conservatives in Beijing.

Government Support

Not all influential Chinese concurred with the imperial government’s suspicion of emigrants. Particularly in the South, certain merchants and officials were making fortunes from foreign trade, and many undoubtedly realized that it was not enough to sit passively in Canton (Guangzhou) waiting for foreign traders to come to them. This meant, according to an already-ancient principle, that some Chinese had to go abroad in order to facilitate the import and export businesses. Hence, the immensely wealthy and politically powerful traders of Guangzhou, whose fortunes depended on as much on Chinese miners and merchants in Southeast Asia, Australia, and America as on Europeans bringing goods like opium and cotton to China, were whole-heartedly in favor of emigration.